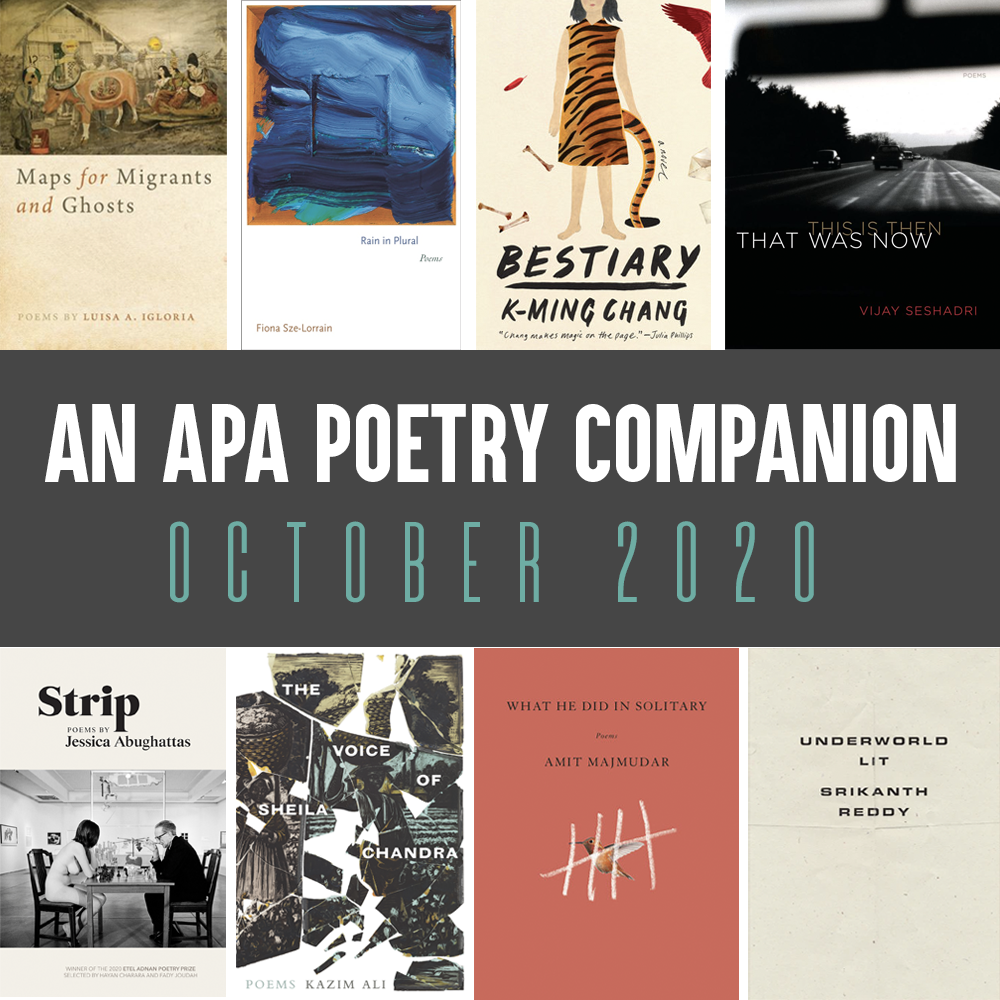

As the leaves change colors and fall, here are a few September and October books by APA poets and writers we’re excited to dig into.

FEATURED PICKS

Kazim Ali, The Voice of Sheila Chandra, (Alice James Books, Oct. 2020)

We’re excited to see that Kazim Ali has a new poetry collection out, The Voice of Sheila Chandra. Named after a singer who lost her voice, the book weaves three long poems together to make a central statement that Ilya Kaminsky says is “far larger than the sum of its parts.” Sam Sax describes the collection as “part research document, part song, part deep excavation of the soul.” With that kind of ringing endorsement, this book is certain to be one we’ll enjoy.

Luisa A. Igloria, Maps for Migrants and Ghosts, (Southern Illinois University Press, Sep. 2020)

Two-time contributor Luisa A. Igloria, who was recently named poet laureate of Virginia, also has a new book out this fall. Maps for Migrants and Ghosts explores the diasporic experience and brings in the poet’s own personal history, from the Philippines to her immigrant home in Virginia. We’re big fans of Igloria’s work here at LR, and we look forward to reading her latest.

Srikanth Reddy, Underworld Lit, (Wave Books, Aug. 2020)

Wave Books describes Srikanth Reddy’s Underworld Lit as “a multiverse quest through various cultures’ realms of the dead.” A serial prose poem, the book takes readers on a “Dantesque” tour from professor’s classrooms to Mayan underworlds and beyond. We’re excited to dip into this epic journey in verse and hope you’ll check it out, as well.

Fiona Sze-Lorrain, Rain in Plural, (Princeton University Press, Sep. 2020)

Issue 6 contributor Fiona Sze-Lorrain’s fourth book of original poems, Rain in Plural, just hit shelves last month. In this collection, she uses language to uncover questions of citizenship, memory, and image. We love Sze-Lorrain’s lush, musical sensibilities and have covered several of her previous books on the blog. If you’ve enjoyed her work in the past, you’re sure to enjoy Rain in Plural, too!

* * *

MORE NEW AND NOTEWORTHY TITLES

Jessica Abughattas, Strip, (University of Arkansas Press, Oct. 2020)

K-Ming Chang, Bestiary, (Penguin Random House, Sep. 2020)

Amit Majmudar, What He Did in Solitary, (Penguin Random House, Aug. 2020)

Vijay Seshadri, That Was Now, This is Then, (Graywolf Press, Oct. 2020)

* * *

We hope you‘ll curl up with some of these picks this upcoming fall. What else is on your reading list? Share your recommendations with us in the comments or on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram (@LanternReview).

* * *

ALSO RECOMMENDED

Every Day We Get More Illegal by Juan Felipe Huerrera (City Lights Publishers, 2020)

Please consider supporting an independent bookstore with your purchase.

As an APA–focused publication, Lantern Review stands for diversity within the literary world. In solidarity with other communities of color and in an effort to connect our readers with a wider range of voices, we recommend a different collection by a non-APA-identified BIPOC poet in each blog post.