Panax Ginseng is a bi-monthly column by Henry W. Leung exploring linguistic and geographic borders in Asian American literature, especially those with hybrid genres, forms, vernaculars, and visions. The column title suggests the English language’s congenital borrowings and derives from the Greek panax, meaning “all-heal,” together with the Cantonese jansam, meaning “man-root.” This perhaps troubling image of one’s roots as panacea informs the column’s readings.

*

*

1. Diptych

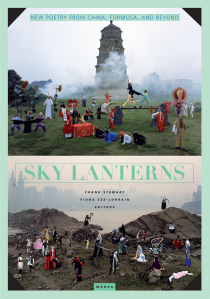

Manoa’s recent “Sky Lanterns” issue spotlights “new poetry from China, Formosa, and Beyond.” The issue features contemporary poets organized in order of age: “not as a bow to hierarchy,” writes editor Fiona Sze-Lorrain in her prefatory note, “but to trace a possibility sensitive to time.” From a first glance at the cover, we see a juxtaposition of the old and the new in the grandly staged Soul Stealer, photographs by artists Zeng Han and Yang Changhong. In the diptych’s top half is Mulian Opera #11: costumed figures of an ancient theater tradition, including mythic animal avatars such as the monkey king, who populate a green landscape with a seven-story pagoda obscured by mist. Meanwhile, in the bottom half is World Warcraft #11 (dated a year later): costumed figures of neo-contemporary archetypes, including the princesses, warlocks, and demons familiar to role-playing video gamers, who populate a craggy landscape with a line of skyscrapers obscured by what may be polluted smog. The “possibility sensitive to time” in the photographs is appropriate to this volume because the costumed figures above and below reflect the modulations of culture, place, and society over time—and yet exist as avatars of myth and imagination outside of time. The same might also be said of the figures and expressions of poetry.

The volume opens with Bei Dao’s essay “Ancient Enmity,” which frames our reading with the enmities he claims exist between the poet and the poet’s era, mother tongue, and self. Bei Dao quotes Rilke’s “ancient enmity / between our daily life and the great work,” which also calls to mind Yeats’s choice between “perfection of the life or of the work.” One is invited to read the chronologically arranged poems in this volume with an attention toward how poetry’s relationship or antipathy to the world has changed. An ironic continuity emerges, at once apologia and apology for poetry in the world, as we see in the ending of “Doubt” by Amang:

a certain longevity

rubbish

poetry and song

The translation is interesting here: “certain” calls to mind certainty, yet is undercut by the preceding article “a” (there are no articles in Chinese) to mean finally a type, a mere kind of longevity. And on either side of the word “poetry” are juxtapositions by what may be synonyms: both “rubbish” and “song.”

“Song” is another word of interest because Luo Dan’s photographs, interspersed throughout the volume, come from a series entitled Simple Song. In an end note, we’re told that these are photos of the Lisu ethnic minority in a remote, autonomous region of Yunnan, and that the photographs were made through the laborious collodion wet plate process. It’s a long process which yields “exquisite detail,” but “during which time the subject must remain perfectly still.” For some of these photographs, especially those in which scenes are suggested (#24: two women of great contrast in color and size face each other on a narrow path; #25: John raises his hand to ring a bell in Laomudeng Village), this means the illusion of candidness. Sze-Lorrain’s first sentence in her prefatory note is: “While my impulse in composing this note was to think aloud, this first sentence has already been revised more than once.” I mention all this to gesture at the labor that goes into seeming simplicity, the staging and revision required. The process of such labor is an enmity with language, which can fog or halt as much as it might elucidate or open.

2. Time

The first three poets in the volume mark a rapid chronological trajectory. (It’s worth noting also that, though veiled by the translation, language evolves through time in the volume: the first few poets write in Traditional Chinese, until Yang Liang marks a turn toward Simplified, and from that point forward only Amang, who resides in Taiwan, writes in Traditional.)

Li Shangyin, a poet from the Tang Dynasty (813–858), makes use of that era’s poetic tropes: allusions to the seasons, meditations on the moon, and the sound of music in imperial settings. “Yet, rancor,” reads one line. Another line hits the same tenor of undercut beauty: “Worth grieving, how a little garden becomes the long road.” And on the limits of human kinship, the poet says further:

Today a pine on the ravine floor,

tomorrow a cork-tree on mountain’s peak.Agony: when heaven, earth, are overturned

we will see each other, we will not be known.

That is a despairing observation of change. Yet the following poet in the volume is Arthur Sze, born centuries later in New York in 1950. That’s a wormhole in time, and perhaps an attempt to form a continuity which historicizes contemporary writing. Sze writes in English in a rather different tenor:

if she bows and hears applause

then puts her bow to the string,

if she decides, “This is nothing,”

let the spark ignite horse become

barn become valley become world.

This is the ending of “Arctic Circle,” and the poem’s cosmic interrelatedness is a variation on Sze’s use of the sublime, an exquisite illusion of cause-and-effect that is ultimately shown to be synchronicity. The sparks are constant, and the world is, if not united, at least connected.

The third poet in the collection, Ling Yu (b. 1952 in Taipei), offers a long poem entitled “Myself, My Train, and You,” in which meditative travel bridges the distance between times and people. In the second section of the poem, the speaker names items in her suitcase: “candle, / Notebook, Dickinson. The nineteenth century / And myself, pressed in each other’s palms.” We encounter Borges, Baudelaire, Plath, Tsvetaeva, a third-century barmaid, a fourth-century landscape, twentieth-century ideologies, and this question:

Has the universe gotten too narrow?

How does a thing get buried?

Put the train out of mind . . .

Later we are pointed to “the train that is Mother,” and see the narrow vestibule of travel making nothing of a cliff or abyss: “End of a century / Just another day / Start of a century / Just another day . . .”

3. Place

It’s remarkable to consider that a collection of writing organized under the conceit of locality brings us finally back to the universal: across localities, boundaries of era or language. We see this enacted in geographic landscape, too: Karen An-hwei Lee’s short work of fiction, “Vestiges of Sea Pilgrims,” with its haibun-like dialogue with Emily Dickinson, guides us through places of water in Los Angeles as a whirlpool into Venezia, Rome and Greece, Japan, and Paris. This is an expansive instance of the “And Beyond” we encountered in the anthology’s title.

Woeser’s essay, “Rinchen, the Sky-Burial Master,” deals with natural landscape as place but also as identity. The essay is a short piece of ethnography whose central anguish is how to represent a piece of one’s culture without exoticizing it. The essay begins sharply: “Another writing about a sky-burial master is sure to be suspected of having chosen a sensational subject just to get attention. When one brings up sky burials, all kinds of exotic stereotypes about Tibet leap to mind.” (This might also apply to Sky Lanterns itself, of course, which has proven idiosyncratic and cosmopolitan even in its representation of Tang Dynasty poetry.) The essay has a pointed awareness of the tourism industry, for better and for worse, and Woeser mentions having gone in a previous year with a TV production team from Taiwan to see a staged sky-burial, in which a dressed-up cow’s leg was used instead of a human corpse. She’s also aware of the gaze trained on her by others: that traveling with two cameras around her neck makes people assume she holds the permissions of a traveling journalist.

Early in Woeser’s journey, she comes to a moment of self-revelation when she and Tashi, a horse-keeper, are left alone in the woods. She is overwhelmed by nature and wants to sing out, but cannot do so: “I realized that I was a Tibetan who had been estranged from the natural landscape for too long. Tashi, on the other hand, simply burst into song . . .” (This resonates with a note from translator Thomas Moran at the beginning of another essay in the book: “For Wei An, the essence of Thoreau was not a ‘return to nature’ but rather the ‘completion of man.’ ”)

Which of course makes one wonder: is there any resting point for us as people and as writers? It’s a question worth consideration if we are to use language to reach across geographies and self-understandings. Consider these thoughts from Woeser, which seem to suggest that we don’t need a resting place, that the ambivalence of our identities is a kind of synchronicity across time. She notes, after having gotten to know the sky-burial master Rinchen:

Although it could be said he had several identities, I understood that deep down he was, after all, a typical nomad. The identity had been given to him by history, but his identity seemed to me redundant now, and vanishing without a trace. It was futile to expect that I could have found in him the identity that I had sought in the beginning. Somehow, this made me feel sad, but also relieved. It is precisely the pluralism of their identities that turns a great many Tibetans into two, three persons, sometimes even more.

Many thanks for these meditative and incisive comments on SKY LANTERNS. The review is a wonderful piece of writing in itself.

Thank you for your kind words, Pat. We’re glad you enjoyed Henry’s post, and are grateful to MANOA for giving us the chance to review SKY LANTERNS in the first place!