Panax Ginseng is a bi-monthly column by Henry W. Leung exploring linguistic and geographic borders in Asian American literature, especially those with hybrid genres, forms, vernaculars, and visions. The column title suggests the English language’s congenital borrowings and derives from the Greek panax, meaning “all-heal,” together with the Cantonese jansam, meaning “man-root.” This perhaps troubling image of one’s roots as panacea informs the column’s readings.

*

*

1. Diptych

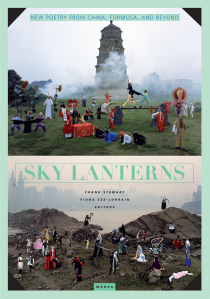

Manoa’s recent “Sky Lanterns” issue spotlights “new poetry from China, Formosa, and Beyond.” The issue features contemporary poets organized in order of age: “not as a bow to hierarchy,” writes editor Fiona Sze-Lorrain in her prefatory note, “but to trace a possibility sensitive to time.” From a first glance at the cover, we see a juxtaposition of the old and the new in the grandly staged Soul Stealer, photographs by artists Zeng Han and Yang Changhong. In the diptych’s top half is Mulian Opera #11: costumed figures of an ancient theater tradition, including mythic animal avatars such as the monkey king, who populate a green landscape with a seven-story pagoda obscured by mist. Meanwhile, in the bottom half is World Warcraft #11 (dated a year later): costumed figures of neo-contemporary archetypes, including the princesses, warlocks, and demons familiar to role-playing video gamers, who populate a craggy landscape with a line of skyscrapers obscured by what may be polluted smog. The “possibility sensitive to time” in the photographs is appropriate to this volume because the costumed figures above and below reflect the modulations of culture, place, and society over time—and yet exist as avatars of myth and imagination outside of time. The same might also be said of the figures and expressions of poetry.

The volume opens with Bei Dao’s essay “Ancient Enmity,” which frames our reading with the enmities he claims exist between the poet and the poet’s era, mother tongue, and self. Bei Dao quotes Rilke’s “ancient enmity / between our daily life and the great work,” which also calls to mind Yeats’s choice between “perfection of the life or of the work.” One is invited to read the chronologically arranged poems in this volume with an attention toward how poetry’s relationship or antipathy to the world has changed. An ironic continuity emerges, at once apologia and apology for poetry in the world, as we see in the ending of “Doubt” by Amang:

a certain longevity

rubbish

poetry and song

Continue reading “Panax Ginseng: “A Possibility Sensitive to Time””