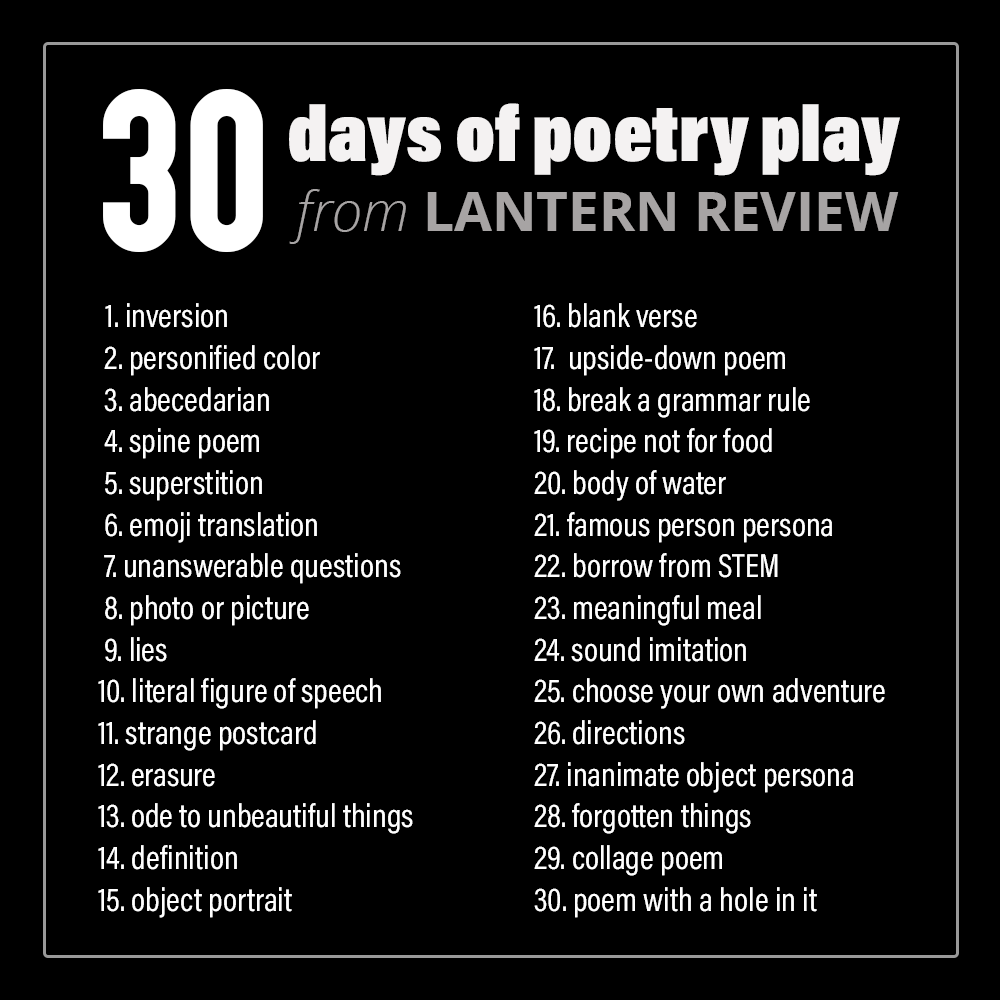

Happy National Poetry Month! In honor of the occasion, we’re sharing thirty of our favorite, most imaginative, playful prompts with you on the blog this morning. Whether you’re participating in NaPoWriMo and writing a poem every day this month or you’re just looking for some occasional inspiration, we hope these prompts will bring out your inner, childlike creativity and help you refresh and renew your writing practice—during April or any time of year. (Pro tip from this former classroom teacher: these tried-and-tested prompts work great for young writers, too!)

* * *

30 DAYS OF POETRY PLAY

- Write an opposite poem (inversion). Take any famous poem and write the exact opposite of it, line by line. If the poem describes a “warm and fluffy towel,” turn it into something like “icy, hard concrete.” If the poem says that the speaker “sprinted,” have them “crawl.”

- Write a poem about a color as if it were a person. Describe what it sounds and smells like, what it dreams about at night.

- Write an abecedarian poem. Start with a line that begins with A, then add a line that begins with B, and so on, all the way down to Z. For an extra challenge, try continuing your sentences over multiple lines.

- Stack up some books with their spines facing out and use their titles to make a poem.

- Make up a superstition and write about what might happen if people don’t follow it.

- Translate a classic poem into all emojis, word by word.

- Write a poem that consists entirely of questions nobody can answer (like: “Where does the snow hide its mittens?”).

- Find a picture or photo that intrigues you and write about what you see.

- Write a poem that consists entirely of lies; the sillier the better.

- Write a poem that takes a figure of speech literally. (What would happen if it really did rain cats and dogs from the sky?)

- Write a postcard about the weirdest place you could imagine (like inside your sock drawer or on top of spaghetti covered with cheese), but describe it as if it’s an amazing vacation spot. Then mail it to a friend.

- Make an erasure poem by taking another piece of writing (anything—like junk mail or the newspaper) and crossing out words with a thick, dark marker. The words that you keep are the poem.

- Write a serious ode (a poem of praise) to an extremely ordinary, boring, or ugly object.

- Write a poem in the form of an alternative definition for a word—using a meaning that you might not find in the dictionary. Get creative; tell a story about it or give examples.

- Write a portrait of someone you know by describing an object that reminds you of them.

- Write a poem in blank verse. That’s a poem that doesn’t rhyme and where every line follows this beat: ba-BUM, ba-BUM, ba-BUM, ba-BUM, ba-BUM.

- Write about a journey. Then make an upside-down poem by reversing what you just wrote so that the last line becomes the first line, the second-to-last line becomes the second line, and so on.

- Write a poem where you intentionally break one grammar rule over and over again.

- Write a recipe for something that isn’t food.

- Make up a descriptive name for an imaginary body of water (like “The Bay of Cats” or “The Popcorn Sea”) and write a poem about that place.

- Write a poem in the voice of a historical person or fictional character.

- Borrow a line from a science or math book or article and use it as the title of a poem.

- Write about a meal shared with someone you miss.

- Write a poem about an activity where the sounds of the words imitate the sound of what you’re doing. If you’re jumping in leaves, crunch and crackle your way through each crisp line. If you’re drinking boba, let your words slurp and slosh and quietly squish against your teeth.

- Write a choose-your-own-adventure poem where the reader gets to choose which line to read next.

- Write a poem in the form of directions to a place (real or imaginary) that is important to you.

- Write a poem in the voice of an inanimate object.

- Write a list of things that you’ve forgotten. Then turn that list into a poem.

- Cut up a newspaper or magazine article, then rearrange the words and make as many of them as you want into a collage poem.

- Write a poem with a hole (literal, typographical, or figurative) in the middle of it.

* * *

We’d love to see what you create with these prompts! Share a snippet with us on the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram (@LanternReview) using the hashtag #LR30DaysofPoetryPlay. Happy writing!