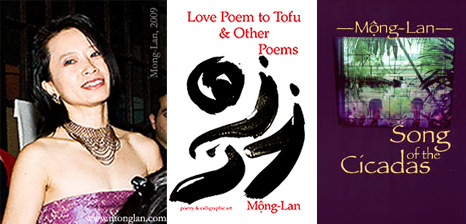

Mong-Lan is a Vietnamese-born American poet, writer, painter, photographer, and Argentine tango dancer and teacher. Mong-Lan’s first book of poems, Song of the Cicadas, won the 2000 Juniper Prize from UMASS Press and the 2002 Great Lakes Colleges Association’s New Writers Awards for Poetry. Her other books of poetry include Why is the Edge Always Windy?; Tango, Tangoing: Poems & Art, the bilingual Spanish / English edition, Tango, Tangueando: Poemas & Dibujos and Love Poem to Tofu and Other Poems (chapbook). A Wallace E. Stegner Fellow in poetry for two years at Stanford University and a Fulbright Fellow in Vietnam, Mong-Lan received her Master of Fine Arts from the University of Arizona. Her poetry has been frequently anthologized, having been included in Best American Poetry, The Pushcart Book of Poetry: Best Poems from 30 Years of the Pushcart Prize; Asian American Poetry —The Next Generation, and has appeared in leading American literary journals. Her paintings and photographs have been exhibited at the Capitol House in Washington D.C., for six months at the Dallas Museum of Art, at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, in galleries in the San Francisco Bay Area, and in public exhibitions in Tokyo, Bali, Bangkok, Buenos Aires and Seoul. Based in Buenos Aires, Mong-Lan travels frequently. Visit: www.monglan.com

LR: You are both a visual artist and a poet, and both of these art forms have a strong presence in your books. How have your sensibilities as a visual artist have influenced your poetry’s aesthetic? Did you come to one through the other? At what point did the two interests begin to intersect?

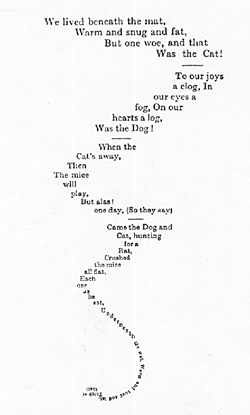

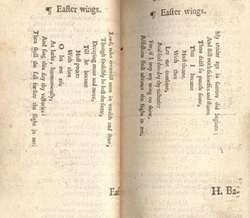

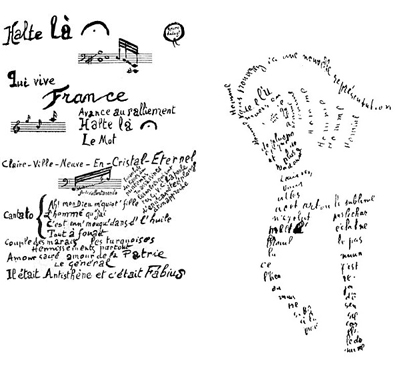

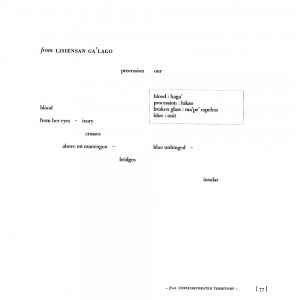

ML: My sensibilities as a visual artist have influenced greatly my poetry’s aesthetic. The open field of the page is important to me, just as the blank canvas or white sheet of paper is to the visual artist. When writing poetry, I think in spatial terms, not just linearly. So, in this way, I concern myself with the placement of words on the page, using the way words bounce off each other, the connotation of words next to each other, above, below, to the right and left, and diagonal. In Tango, Tangoing, my latest book, you can read certain poems not only left to right, but down one column, then down another column.

I didn’t come to one art through the other. A visual artist since childhood, I showed my artworks in Houston and then in San Francisco, where I flowered and came to mature as a visual artist in the very liberal atmosphere there. At the same time, I was writing since high school, scribbling in journals my feelings, emotions, narratives, stories and things that I couldn’t depict visually in paintings.

Both poetry and the visual arts are twin sisters, and it’s easy for me to shift from one to the other. I find that these arts complement each other. And, so, there in San Francisco in the 90’s, I found myself as a poet as well as a visual artist, giving readings with other Vietnamese-American writers/poets.

LR: When you are putting together a collection of poems that will include visual artwork — how do you view the art in relationship to the text? Do you see the art as illustrations of your poems? As a kind of visual poetry in and of itself?

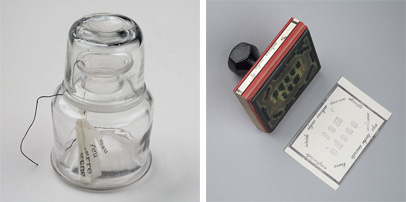

ML: In my first two books, Song of the Cicadas and Why is the Edge Always Windy?, the text is primary, and the visuals secondary. The artwork in both books were used more as appetizers and section dividers. In Song of the Cicadas, I included pen and ink drawings that I drew when I was in Vietnam, the same time I was writing the book itself. It just happened, naturally and synchronistically like that.

Because many people commented on my artwork in both books, I decided to include more of them in my next books. In the chapbook, Love Poem to Tofu & Other Poems, and in Tango, Tangoing: Poems & Art, the artworks are very integral to the books, indeed [they] complement the text a great deal, although the texts can stand by themselves. There are many more drawings/paintings in these latter two books—they’re more like entrees and not just appetizers.

The artworks in my books can stand by themselves; thus, they are not mere illustrations. Yet, they do illuminate the text and add another dimension to it. Yes, I would consider my artworks a kind of visual poetry in and of itself.

Li-Young Lee – “Every Circle Wider”

Li-Young Lee – “Every Circle Wider” Jeffrey Yang – “Wolf Shadow”

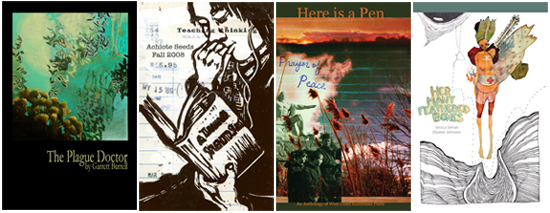

Jeffrey Yang – “Wolf Shadow” Agha Shahid Ali – “Ghazal”

Agha Shahid Ali – “Ghazal” Oliver de la Paz – “If Given” and “Fury”

Oliver de la Paz – “If Given” and “Fury” Barbara Jane Reyes – “Polyglot Incantation”

Barbara Jane Reyes – “Polyglot Incantation”

![fromunincorporatedterritorysaina from UNINCORPORATED TERRITORY [SAINA]](http://lanternreview.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/fromunincorporatedterritorysaina.jpg)