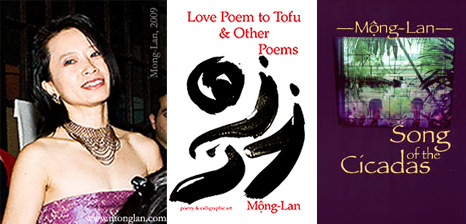

Mong-Lan is a Vietnamese-born American poet, writer, painter, photographer, and Argentine tango dancer and teacher. Mong-Lan’s first book of poems, Song of the Cicadas, won the 2000 Juniper Prize from UMASS Press and the 2002 Great Lakes Colleges Association’s New Writers Awards for Poetry. Her other books of poetry include Why is the Edge Always Windy?; Tango, Tangoing: Poems & Art, the bilingual Spanish / English edition, Tango, Tangueando: Poemas & Dibujos and Love Poem to Tofu and Other Poems (chapbook). A Wallace E. Stegner Fellow in poetry for two years at Stanford University and a Fulbright Fellow in Vietnam, Mong-Lan received her Master of Fine Arts from the University of Arizona. Her poetry has been frequently anthologized, having been included in Best American Poetry, The Pushcart Book of Poetry: Best Poems from 30 Years of the Pushcart Prize; Asian American Poetry —The Next Generation, and has appeared in leading American literary journals. Her paintings and photographs have been exhibited at the Capitol House in Washington D.C., for six months at the Dallas Museum of Art, at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, in galleries in the San Francisco Bay Area, and in public exhibitions in Tokyo, Bali, Bangkok, Buenos Aires and Seoul. Based in Buenos Aires, Mong-Lan travels frequently. Visit: www.monglan.com

LR: You are both a visual artist and a poet, and both of these art forms have a strong presence in your books. How have your sensibilities as a visual artist have influenced your poetry’s aesthetic? Did you come to one through the other? At what point did the two interests begin to intersect?

ML: My sensibilities as a visual artist have influenced greatly my poetry’s aesthetic. The open field of the page is important to me, just as the blank canvas or white sheet of paper is to the visual artist. When writing poetry, I think in spatial terms, not just linearly. So, in this way, I concern myself with the placement of words on the page, using the way words bounce off each other, the connotation of words next to each other, above, below, to the right and left, and diagonal. In Tango, Tangoing, my latest book, you can read certain poems not only left to right, but down one column, then down another column.

I didn’t come to one art through the other. A visual artist since childhood, I showed my artworks in Houston and then in San Francisco, where I flowered and came to mature as a visual artist in the very liberal atmosphere there. At the same time, I was writing since high school, scribbling in journals my feelings, emotions, narratives, stories and things that I couldn’t depict visually in paintings.

Both poetry and the visual arts are twin sisters, and it’s easy for me to shift from one to the other. I find that these arts complement each other. And, so, there in San Francisco in the 90’s, I found myself as a poet as well as a visual artist, giving readings with other Vietnamese-American writers/poets.

LR: When you are putting together a collection of poems that will include visual artwork — how do you view the art in relationship to the text? Do you see the art as illustrations of your poems? As a kind of visual poetry in and of itself?

ML: In my first two books, Song of the Cicadas and Why is the Edge Always Windy?, the text is primary, and the visuals secondary. The artwork in both books were used more as appetizers and section dividers. In Song of the Cicadas, I included pen and ink drawings that I drew when I was in Vietnam, the same time I was writing the book itself. It just happened, naturally and synchronistically like that.

Because many people commented on my artwork in both books, I decided to include more of them in my next books. In the chapbook, Love Poem to Tofu & Other Poems, and in Tango, Tangoing: Poems & Art, the artworks are very integral to the books, indeed [they] complement the text a great deal, although the texts can stand by themselves. There are many more drawings/paintings in these latter two books—they’re more like entrees and not just appetizers.

The artworks in my books can stand by themselves; thus, they are not mere illustrations. Yet, they do illuminate the text and add another dimension to it. Yes, I would consider my artworks a kind of visual poetry in and of itself.

LR: Tango, Tangoing and Love Poem to Tofu and Other Poems both engage with the use of strong, fluid brushstrokes reminiscent of Chinese calligraphy. The conversation between Western-style poetry and the visual aspects borrowed from a traditional Asian form of poetic expression is truly fascinating. How would you describe your aims in juxtaposing the two?

ML: Well, I was living in Tokyo for five years, from 2002 until 2007, and the brush calligraphy that I saw on a daily basis on the streets was beautifully overwhelming. It invaded my senses! I also took a few classes in brush calligraphy, painting/writing kanji (Japanese for Chinese characters). While the importance of the brush stroke is not new to me, being a painter since childhood, it took on new dimensions of its own as an aesthetic in its own right. I basically use brushstrokes with these same calligraphic techniques and apply them to my art. While one could consider it a “traditional Asian form,” it’s also being practiced left and right in Japan and China and other parts of Asia today. Yes, in my books, you find a juxtaposition of the East and the West, just as in my being and psyche, there’s a juxtaposition of East and West.

LR: The artwork included in your poetry collections employs a variety of different media: whereas Tango, Tangoing and Love Poem to Tofu engage with a more painterly style, Song of the Cicadas features line drawings between its sections and one of your photographs on its cover. Can you talk a little bit about your process in deciding what sorts of visual media will best lend themselves to a text? How has the arc of your visual/textual projects evolved from book to book?

ML: My first two books were written from 1995 – 2000, although they were published later — Song of Cicadas in 2001, and Why is Edge Always Windy? in 2005. My mentor at the time when I was putting Song of the Cicadas together, Jane Miller, suggested that photography catches people’s eyes more. At that time, I was working on these montage photographs of Vietnam, and I decided to use [one] for the cover. Luckily, the publisher liked it.

As mentioned earlier, I lived in Tokyo from 2002-2007, and during this time, I was working on the later two books, Love Poem to Tofu and Tango, Tangoing. It was a function of my environmental influences, more than anything. The art I was creating was influenced greatly by where I was living and the environment I was immersed in. And I simply used this art for my books.

LR: Last month on the LR Blog, we did a number of posts about ekphrastic poetry. How do you engage with ekphrastic processes in your work? What visual artists have most inspired you? Do your poems ever emerge from pieces of your own artwork?

ML: No, I don’t think poems ever emerge from pieces of my own artwork, although, it’s an interesting idea. I’ve never written about a painting I’ve done, because it seems to me that once I’ve painted it, I can move to a different theme or idea and not repeat it in writing.

But, I have, for example, used the tango as an inspiration, and have written poetry stemming from the experience of tango. And, in the same book, included drawings of tango dancers, what I saw in the tango dance halls, or milongas. So, in this instance, my artistic activities stemmed from the same source.

I have taught classes in which I gave my students that as an assignment, ekphrastic poetry, and it has been helpful in exploring a visual artist’s psyche, ideas and intentions.

With regard to artists that have inspired me, I have loved Kandinsky’s paintings for his use of color and that of Paul Klee for his whimsicality and playfulness.

LR: In many ways, you are an artist whose work expands across (even defies) linguistic and national boundaries. You were born in Vietnam, and the Vietnamese language occasionally makes little cameo appearances in your poetry. Tango, Tangoing has also been released in a bilingual Spanish-English edition. How would you position yourself in relation to these multiple linguistic modes — and how does your engagement with them inform your work?

ML: I grew up speaking Vietnamese within the family, and went back to Vietnam several times, first on my own for half a year, then later on a Fulbright Fellowship to write and do research. In those instances I was able to deepen my knowledge of Vietnamese. I’m also fluent in Spanish, and indeed, I love the Spanish language. I am now based in Buenos Aires, and have been based here over a year now. I’ve been coming to Buenos Aires since 2001 for periods of several weeks to a month, for the tango. When I go out onto the streets of Buenos Aires, I feel a sense of elation merely listening to Spanish.

With regard to other languages, I also speak French fluently, and am working on my fluency in Italian. Living in Tokyo for five years, I learned Japanese, but have since forgotten quite a bit. I also lived in Bangkok for six months and took lessons in Thai every day, but it is a difficult language to remember if you aren’t immersed in it everyday.

Knowing these languages has helped me broaden my mind culturally and syntactically, and I think this has deepened my involvement with the English language as well. The English language is a rich language that generously takes in other languages. In my writing, I’ve written about the various places I’ve lived, such as Bangkok and Tokyo, and of course Vietnam and Argentina, and knowing the language of the country is essential to understanding its culture.

LR: You are also a dancer. In what ways have the forms and physical knowledge of the human body helped to shape both your poetic craft and visual aesthetic?

ML: Dancing tango gave rise to Tango, Tangoing. Indeed, dancing is an affirmation of the body, the body as a means to express the joy of life, the earth and the universe. I’ve known writers and poets who negate their bodies, and identify only with their minds.

Dancing has taught me to flow in my life as well as in my art. Not only did I begin to write poetry that was a direct result of my tango dance experience, I started to do drawings and also paintings on canvas of tango dancers, showing the movement and flow of the dance. More than the form and physical knowledge of the human body, dance has taught me to flow in other areas of my life.

LR: What projects are you working on at the moment?

ML: I’m working on a novel, another book of poems, paintings on canvas and paper, photography, and tango choreography. I’m also working on a catalog of my paintings and artwork. It’s a handful!

LR: What advice would you give to younger poets who might be considering how to integrate their engagement with visual or performing arts with their writing?

ML: Experiment with everything you know. See how your interests fit together synergistically. Learn from tradition, but don’t be afraid to break it. And, enjoy your work!