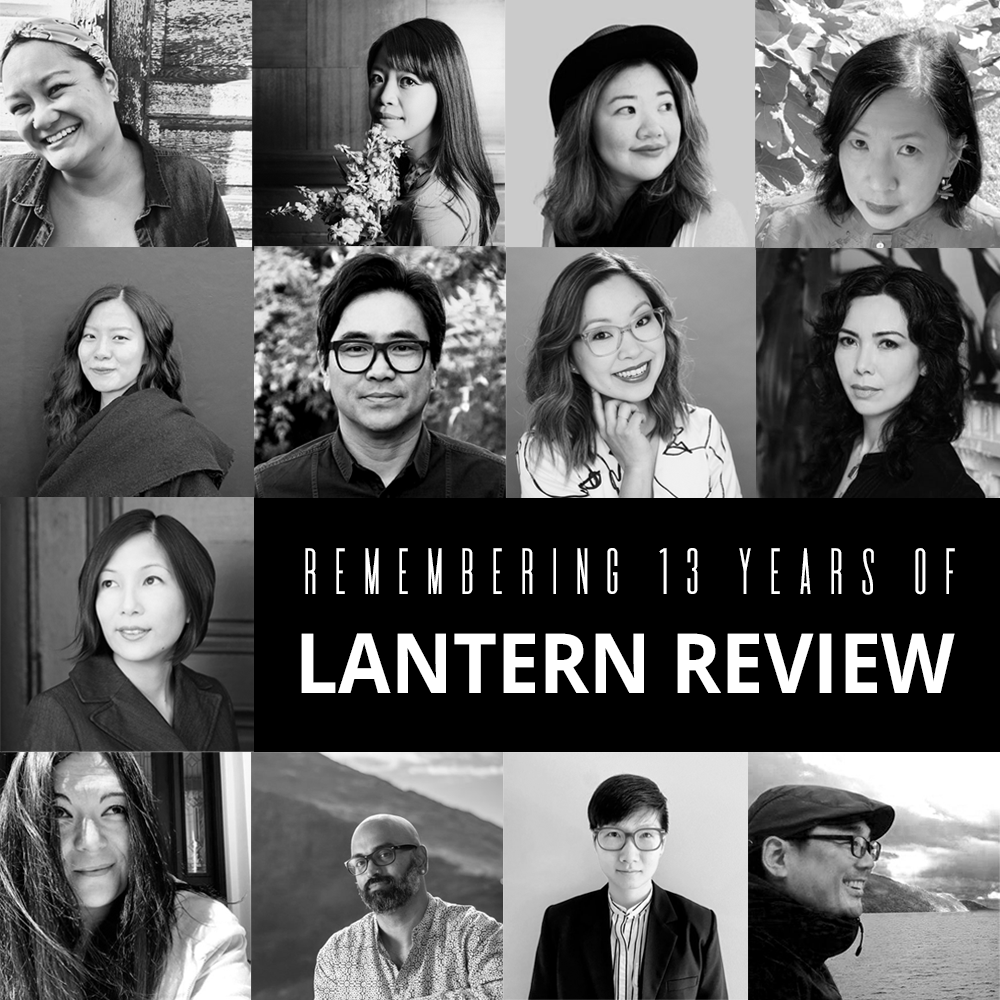

As Lantern Review wraps up its final season, we thought we’d take some time to reflect back on the past thirteen years. We asked some of our community to share about what the magazine has meant to them, and we were touched by the overwhelming kindness and generosity of their responses.

A common thread among our contributors’ and staff members’ remarks was the space Lantern Review has created over the years for Asian American writers.

“I am so grateful to have been a contributor to Lantern Review’s issue on Asian American futures,” said Issue 9.3 contributor Cat Wei. “In the wake of anti-Asian hate, this space created by Lantern Review has been part of the important work of reclamation—of our own stories and pasts and future stories. Thank you for the beautiful vocoder you’ve shared with the world.”

Former staff columnist Kelsay Elizabeth Myers also touched upon the safe space that Lantern Review provided to explore, experiment, and play with the textuality and materiality of one’s identity:

“For me, Lantern Review meant a refuge: a place where I could be free to speak my mind and shine my own light among others in the Asian American poetry community. LR was one of the first Asian American journals I discovered after my initial experiences with racism in my twenties, and it was the first one dedicated to poetry and craft. It gave me a brave space to form radical ideas about poetry and make sense of my own personal experiences before I knew what a brave space was. And in the LR space, I was given the opportunity to experiment with my own craft ideas between poetry and creative nonfiction, between the whiteness and the Korean aspects of my identity, and between the ideas of identity and selfhood that still influence my life and work to this day.”

Two-time contributor Rajiv Mohabir discussed the importance of the community that Lantern Review has cultivated, especially with the increase in anti-Asian hate crimes in the past few years:

“Lantern Review has been an important way that we have been able to see ourselves. There are so few literary journals where Asian American voices can congregate, and LR has been one that has been remarkable and culturally responsive to us in such trying times. I loved reading the poems and reviews of writers who I know and being exposed to those I had not yet encountered. I will forever be grateful to the editors and the community that they cultivated.”

For some, being part of a community has created lifelong friendships and allowed them to explore new voices within the Asian American poetry world:

“In 2011, I’d just moved back to the US after fifteen years in the UK and ten years out of poetry when I saw that Lantern Review was looking for a staff interviewer,” said former staff writer Wendy Chin-Tanner. “I got the position, and what I thought would be a helpful reintroduction to the APIA poetry landscape quickly became much, much more. Through working with Iris and Mia, and interviewing poets like Patrick Rosal, Lee Herrick, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Kimiko Hahn, and Don Mee Choi, to name just a few, I was embraced by a community in which I’ve built lasting, treasured relationships. Thank you, Iris and Mia, for the opportunity and the friendship, and for creating such a beautiful, welcoming space for APIA poetry.”

Karen Zheng, current staff reader and former intern, made similar remarks. “Lantern Review is a warm and uplifting journal providing a space for the Asian and Asian American community,” she said. “It brought me a sense of belonging amongst other poetry circles. I always recommended people read Lantern Review if they get a chance. Some of the best voices of our time have emerged through Lantern Review.“

For Issue 9.1 contributor Joan Kwon Glass, Lantern Review has provided a kind of community she didn’t always have access to. She’s even implemented poems published in our journal as part of her poetry class curriculum.

“Lantern Review has been the kind of beloved community for writers that I dreamt of as a child. Growing up in a Midwestern home as a mixed-race Korean American girl, I lived in between lands. Finding a home for my writing about this specific experience as well as having my book appear on their Asian American poetry blog have been two of my fondest publication memories. LR has also served as a treasure trove of work from which I have pulled to teach poetry classes. I will miss it and always be grateful for guest editor Eugenia Leigh and editor/founder Iris Law.”

Others wrote about their personal experiences reading each issue that Lantern Review has published.

“I adore Lantern Review—each issue feels like sitting at the dinner table with so many of my Asian American beloveds,” said two-time contributor Jane Wong. “Thank you for championing emerging writers and for shouting out fresh books! We love you!”

Issue 6 contributor Lee Herrick also noted what it’s felt like to him after reading each issue.

“Lantern Review has been a source of nourishment, light, and inspiration,” Herrick said. “I felt renewed after each issue, edited with such care, full of such necessary writing. I will miss it, but I am grateful for the ten-plus years of publishing stellar Asian American writing. You helped shape American poetry and countless Asian Americans’ creative lives. Thank you for everything, Lantern Review.”

Luisa A. Igloria, whose work has been published in Lantern Review three times, touched upon the myriad of literary and technical representation within the pages of each issue.

“Since its inception, Lantern Review has been a bright light and booster of new Asian American poetries and hybrid work. Every issue has been such a beautiful and generous curation of some of the most exciting work of Asian American poets writing today. I feel so fortunate to have had my work included in Lantern Review‘s pages; I know I’ll miss it; and I hope Iris and Mia will find ways to continue the important work they’ve done, beyond LR. Thank you!”

Lastly, several people mentioned the platform Lantern Review has provided for all different types of poetry and the ways in which the journal has impacted them as a writer.

Issue 9.1 contributor Eddie Kim said, “Lantern Review lives true to its namesake. It gave me a platform through which I could be seen as a poet—something I only truly appreciated when a creative writing teacher told me their students enjoyed my poem ‘In America’ in the (at the time) latest issue of Lantern Review. It was such a nourishing feeling knowing others were reading my work in a classroom (and that they were writing students made it extra special). Even though other people reading your work is the obvious goal when sending out writing, it’s not always clear if it’s actually working (especially if you don’t have a known name). That offering was and is deeply meaningful to me, and I’m grateful to Lantern Review for providing the thoughtful and generous space that made a moment like that happen.”

Issues 2 and 10 contributor Michelle Peñaloza and Issue 3 contributor Monica Ong both spoke about what it meant to them that Lantern Review was among their first publications.

“Lantern Review was one of my first publications and has always been so special to me as a journal created by and publishing Asian American poets,” said Peñaloza. “I appreciate so much the support, love, and care Iris and Mia have shared and shown in the many beautiful years they published Lantern Review. A memory: those amazing stickers with folks’ last names—Ong & de la Paz & . . . etc. [at the 2019 Asian American Literature Festival]. I loved those!”

Ong wrote, “Lantern Review was the first literary journal to publish my visual poetry. Prior to that, I’d shared work primarily in the context of art gallery exhibitions. The editorial team was thoughtful about providing a user interface that allowed readers to zoom in, explore, and read the work closely. Most importantly, they were willing to broaden ideas of what a poem could be for its readership. The editors’ openness to hybridity and Asian American voices contributes vital space to an expansive, complex, and innovative generation of writers making exciting work today. Taking those first steps as a budding poet with Lantern Review alongside writers I truly admire has been meaningful, and I’m so grateful for their continued heartfelt care for Asian American literature throughout the years.”

Lantern Review has always sought to uplift new voices and curate themes that encourage writers, and readers, to examine Asian America. 2021 guest editor Eugenia Leigh made note of this while looking back on her own involvement with the journal over the years.

“When Iris A. Law and Mia Ayumi Malhotra launched Lantern Review in 2010, they created and sustained an incredibly dynamic, necessary, and visionary space for Asian American poetry,” Leigh said. “They published Asian American poets before the mainstream literary world caught on to our power. Lantern Review’s very first issue showcased early poems by poets such as Matthew Olzmann and Ocean Vuong. This was years before Matthew’s first book, Mezzanines, was published. Months before Ocean’s first chapbook, Burnings. Lantern Review published one of my earliest poems as well, in their third issue, three years before my own first book. In 2021, I had the privilege of joining their team as a guest editor to curate three issues highlighting the idea of ‘Asian American Futures.’ This theme challenged us to look deeply at and celebrate the future of Asian Americans through contemporary Asian American poetry, and while I grieve the end of LR’s journey, I am grateful for this call to look forward. What a spectacular future Asian American poetry has thanks, in part, to the work of Iris, Mia, and the LR staff. Lantern Review amplified our voices when so few people and places would. Its contribution to our literary landscape was, without exaggeration, revolutionary.”

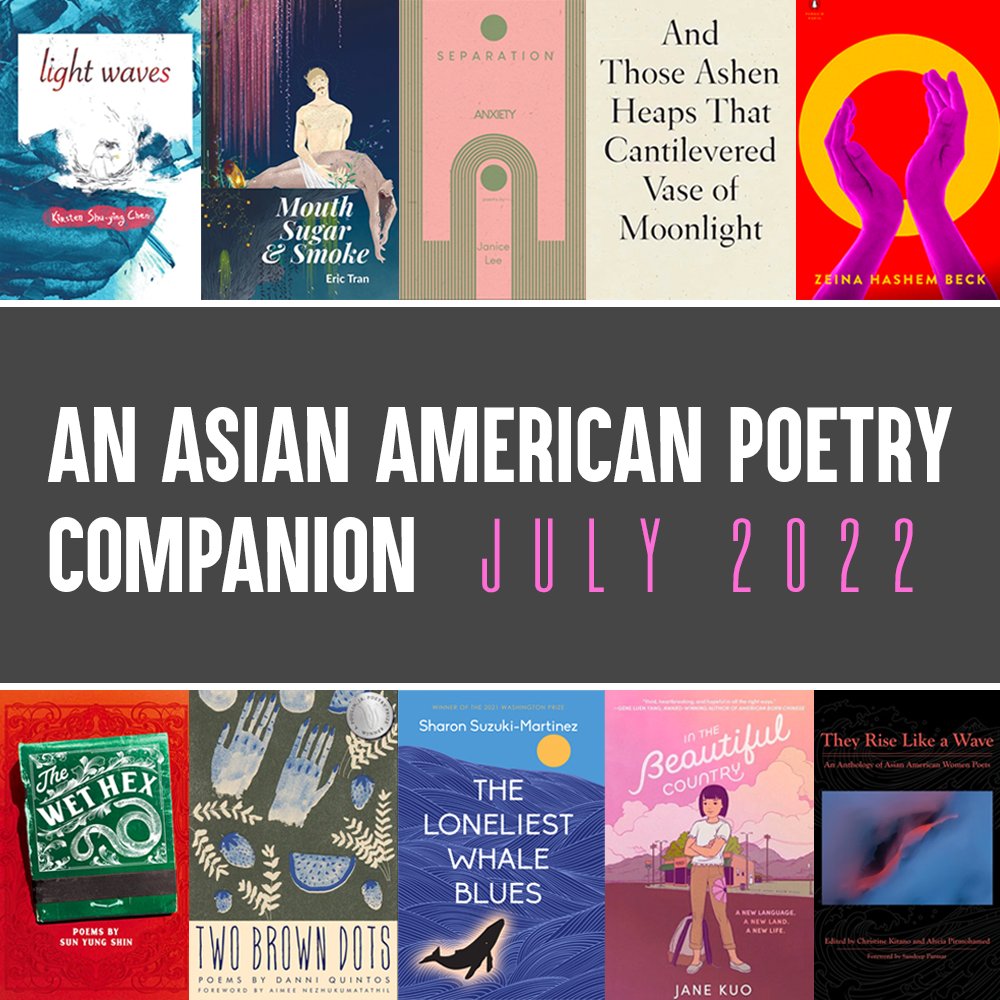

Though Lantern Review is coming to a close, we cannot wait to see what the new year and beyond will bring to the Asian American poetry community. We’re grateful to all those who have submitted, read, and supported Lantern Review throughout the years, and we hope that you’ll always stay hungry for the future of Asian American arts and letters.

* * *

What are some of your favorite memories of Lantern Review? Share them with us in the comments or on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram (@lanternreview).

ALSO RECOMMENDED

Golden Ax by Rio Cortez (Penguin, 2022)

Please consider supporting a small press or independent bookstore with your purchase.

As an Asian American–focused publication, Lantern Review stands for diversity within the literary world. In solidarity with other communities of color and in an effort to connect our readers with a wider range of voices, we recommend a different collection by a non-Asian-American-identified BIPOC poet in each blog post.