This summer, I had the privilege of speaking with E. J. Koh about her memoir, The Magical Language of Others, (Tin House, 2020) as well as her background in poetry and translation. Koh is also the author of poetry collection A Lesser Love, (LSU Press, 2017) and the novel The Liberators, forthcoming in 2023. Her poem “Hysteria” appeared in Issue 9.3 of Lantern Review. Read on for her thoughts on the power of language, writing in different modes and genres, setting the table with multifarious possibilities, and more.

* * *

LANTERN REVIEW: In your memoir, both your college poetry teacher, Joe, and college poetry mentor, Joy, comment on your initial poetry’s lack of “magnanimity.” At the section’s close, you write, “[Joy] encouraged me to look closely, and said poetry would teach me how to pay attention and show me how to care. I must choose love over any other thing. Then, the world would open up for me.” As you’ve continued to grow in your career and craft, even beyond the memoir, have you found this advice—that the practice of caring for one’s craft as a poet is ultimately an exercise in magnanimity—to be true? And is your goal to write one thousand love letters an extension of that same practice of magnanimity?

E. J. KOH: The lesson came around again for my memoir. I had to reckon with the choices I was making on the page. I could put in a scene to argue for my disappointment, for who I’ve become because of what happened to me, but I replaced it with one that challenges how things could’ve been different from what I assumed to know. During a time it was difficult to love, I’d started writing love letters and hadn’t noticed a connection with my work. I wonder if my everyday life is the actual work, and the rest is an extension of how I am living. But writing the letters has given me other lessons. For one, the word stranger has become stranger to me.

LR: You recently announced that you will be publishing your first novel, The Liberators, in the summer/fall of 2023, which is really exciting news. Originally, you began your writing career as a poet, and you detail that journey in The Magical Language of Others. Has your background in poetry been influential as you’ve begun experimenting with prose?

EJK: I was watching my old friend walk into my home, and I thought I saw another person they had been and yet another person they would be, all three of them walking together inside. I would read it on a page, and it could be called a device—a thing to be used—and it can be. But it is also life, isn’t it? Writing tries to do what our lives do so effortlessly. The form seems determined by the force.

LR: Language, obviously, is a central focus in the book. It’s something you study and learn and then pull apart to reveal the intergenerational language used for trauma but also the healing in the language of love. And then, of course, the memoir itself is called The Magical Language of Others. In the book, you observe that “[l]anguages, as they open you, can also allow you to close.” How have you noticed language structuring, opening or closing, your relationships with others or with yourself?

EJK: I was meditating every morning and evening. Some days for five hours. Like it was with languages, I was using meditation to close. I realized I was not waging peace but war. Isn’t it another thing to go outside—to go into those uncertain situations and places? So I try to use meditation, as with my language, to remain open. I welcome my fears because they work diligently to unravel me. I want to look at the things I’m scared of seeing. I want to hear my heart go pitter-patter.

LR: Your graduate workshop professor once said, “If you want to be a good poet, then write poetry. If you want to be a great poet, then translate.” You do a lot of translation work and released last year a cotranslation of Yi Won’s The World’s Lightest Motorcycle with Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bella. How was the process of translating the book as well as translating with a collaborator versus working by yourself? How has translation work in general strengthened your personal poetic practice?

EJK: With Marci, we are part of a sisterhood with Don Mee Choi, Emily Jungmin Yoon, Stine An, and more—along with our poet sisters in South Korea like Kim Hyesoon and Yi Won. So when I’m translating on my own, no matter how I may feel day to day, I cannot ever be alone. And when I meet a translator, I love them right away. A translator knows you so intimately. They can see into your heart. They know how to love you. As a translator, you have to do that with languages. Languages are thorny things, and the way they treat each other sometimes is awful, but there you are, as you were the day before, trying your best.

LR: The first chapter of the memoir, which opens with a letter from your mother, ends with an exhortation to be happy. This command, woven through many of the letters, sometimes reads like a responsibility or a burden. I ask too because I remember my father, when he wrote me letters while I was in college, also encouraging me to be happy, and I recall being perplexed. Happiness was never a present condition I actively sought out or remember being encouraged to be, the latter of which I feel like is a particularly Asian dilemma. Happiness is a prospect to be attained in the future by working hard rather than being happy now. This encouragement to be happy might feel particularly ironic for Asian American children pursuing vocations in the arts and letters (given many parents’ traditional attitudes towards these careers). Do you have any advice for young Asian American artists who may be grappling with parents’ sometimes contradictory expectations?

EJK: Let’s set the table with more possibilities: They ask me to be happy, so I don’t want to be happy, not because it’s what I want but because I know it’s what they want, and I want what they don’t want, or, I can be happy only if things or people are different from what and who they are, and until then, I don’t want to consider being happy, or, I know I can be happy because I understand what it looks like when I’m not but it means they are right and I can’t be happy and wrong, or, I would rather be against someone who is outside the power of my happiness because it helps me separate myself, or, I want them to know they cannot make me happy, though it may be true I’ve given them power over me, or, when I focus on words like happiness and family, I can pick apart their meanings and put myself into them to see what I can or cannot fit, then decide from that, and so on, with new combinations and other possibilities. Nothing is wrong, these things are on the table, and looking at each one, and each one together, you can go beyond them. In the end, what others say for themselves or for you is outside of how you choose your relationship to yourself and the world. The outside can be a warden for the inside, and everything can crumble and [can] do so easily. But if you can go inside of yourself, the outside will catch up. Tell your heart to open and let go.

LR: For your PhD in English literature, you are specializing in Han studies and trauma. What, specifically, are you researching? Do you find that your academic research overlaps with your creative work? Where do you see the similarities between scholarship and creative work in your own personal experience?

EJK: If you look up my poem “American Han” in Poetry magazine, you’ve read my dissertation. My advisor said this and we both laughed. I’m fifty pages into my dissertation, but it’s as if “American Han” didn’t end. I set the table—you can set anything on the table, but nothing can be taken off. So someone says to me, “You’re not Korean, you can’t feel han,” and for some reason, it excites me. I say then, “Please tell me more. Tell me about yourself. Tell me what han means to you.” They say, “There is original han. Original han is for original Koreans who live in Korea.” And I say, “I am listening because I know we can feel better about han together. Will you listen?” There is great darkness with han, yes, but there is also great relief. My research, like my work, means I don’t look away.

LR: Lantern Review’s theme for the season is Asian American Appetites. What’s something that you’re hungry for in the future of Asian American letters?

EJK: [When I am] judging [contests], and I try not to unless I would be especially helpful because it’s another one of those tricky things, but I often read something right out of a pile and get stopped in the middle of it. I’ve read remarkable things by upcoming writers. Things so remarkable I sit up straight and say, “If only the world knew what incredible writers are coming for them. The years and lives it took for these writers to reach us. What things are being written and spoken so that our thoughts and feelings are no longer just our own, and we can be united again in our humanity.” That goes for fiction, nonfiction, memoirs, plays, graphic novels, translations, poems, scripts, young adult, letters, and more. I’m hungry for it all.

* * *

E. J. Koh is the author of the memoir The Magical Language of Others (Tin House Books, 2020), Washington State Book Award winner, Pacific Northwest Book Award winner, Association of Asian American Studies Book Award winner, and PEN Open Book Award longlist. Koh is the author of the poetry collection A Lesser Love (Louisiana State U Press, 2017). Her debut novel, The Liberators, is forthcoming from Tin House Books in 2023.

ALSO RECOMMENDED:

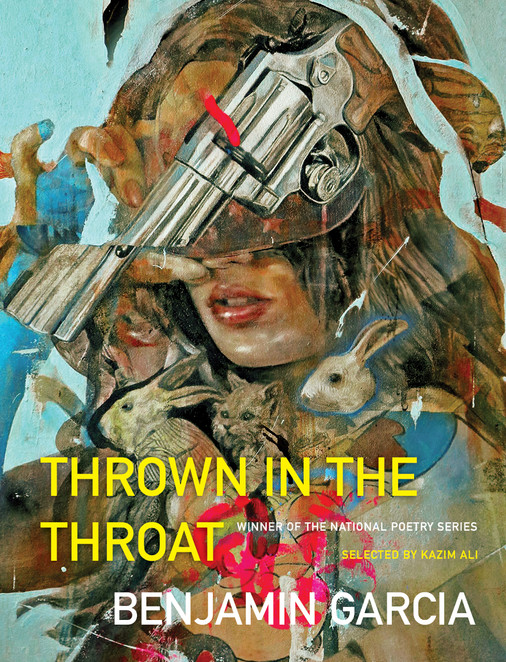

Thrown in the Throat by Benjamin Garcia (Milkweed Editions, 2020)

Please consider supporting a small press or independent bookstore with your purchase.

As an Asian American–focused publication, Lantern Review stands for diversity within the literary world. In solidarity with other communities of color and in an effort to connect our readers with a wider range of voices, we recommend a different collection by a non-Asian-American-identified BIPOC poet in each blog post.