Requiem for the Orchard by Oliver de la Paz | The University of Akron Press 2010 | $14.95

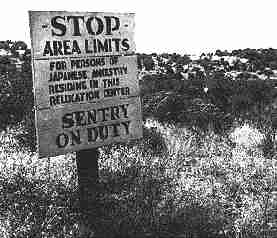

Oliver de la Paz’s third collection, Requiem for the Orchard, is a poignant reminder of both our inability to escape our pasts and our ability to re-write our histories through what we choose to remember. The pieces in this collection are interconnected by the speaker, a young man reflecting on his disenchanted youth. Part meditation on the ways our experiences inform who we are today, part meditation on the ways we cannot shed those experiences despite our efforts, the collection centers around the speaker’s youth spent in a small Oregonian town where he worked a summer job in the orchards.

De la Paz’s tone is often deceptively simple and conversational, as he considers the complex love-hate relationship of the speaker with his hometown as well as the realization that the hate of his youth has dissipated into fond memories. The first poem, “In Defense of Small Towns”, opens with, “When I look at it, it’s simple, really. I hated life there.” Later in the same poem he writes, “But I loved the place once.” As the collection progresses, the reader begins to get deeper glimpses into the process of self-discovery that accompanies the process of reminiscing. In “Self-Portrait as the Burning Plains of Eastern Oregon” he writes: “A blacked-out soda can. Maybe a plastic lid fused to stone. A refusal / to forget childhood’s scald. But also a kind of forgiveness.” As the speaker remembers his childhood, even as he previously resented or denied it, he finds some forgiveness for himself. By the last poem, “Self-Portrait with What Remains”, the speaker reflects on what has stayed with him:

And this? This is what’s left—my night coughs. Slips of news

.

clippings from the old town sent in the mail. The know-how

of tractor management. Now, where once resided

.

acrimony for youth’s black seed—nothing except a single wing

opening and closing and opening again to catch the wind.

De la Paz shows that what lasts through time may not be what we expect, but may instead be the mundane or everyday, and that the speaker’s bitterness has disappeared as he reaches peace with his past. His descriptions of his youth are factual and concrete; the absence that now replaces his anger is beautifully captured in the image of the flapping wing. But to reach this acceptance the speaker must also mourn what is gone. Throughout the collection are a number of poems entitled “Requiem” that truly sing of loss. Although they are ostensibly about the loss of the orchards, they powerfully capture the loss of youth itself. One of these opens with a series of questions that succinctly show the way the loss of the orchards is intertwined with the loss of youth, how the memories for one are tied with memories of the other: “Where lie the open acre and all limns? Where the shade / and what edges? What serrated blades and what cuts? / Where are we, leather-skinned, a spindle of nerves / and frayed edges? What spare parts are we now / who have gone to the orchard and outlasted / the sun and the good boots?” (page 71).

Continue reading “Review: Oliver de la Paz’s REQUIEM FOR THE ORCHARD”