Margaret Rhee is the author of the chapbooks Yellow (Tinfish Press, 2011) and University Dreams (Forthcoming 2012). She is the managing editor of Mixed Blood, a literary journal centered on race and innovative poetics edited by C.S. Giscombe. In April, she curated the literary reading, “Body Maps: A Digital/Real Asian American Feminist Poetics” for the Asian American Women Artists Association. As a new media artist, she works on feminist participatory digital storytelling supporting issues of HIV/AIDS awareness for women incarcerated in the San Francisco Jail. Currently, she is a doctoral candidate in Ethnic Studies and New Media Studies at UC Berkeley. She is a Kundiman fellow.

It begins with a drive. The road up to Santa Cruz from Berkeley is a winding one. Largely known as one of the most dangerous highways in the state, Highway 17 wraps around the Santa Cruz Mountains with sharp pretzel turns and dense traffic on weekday afternoons. It’s my first trip to Santa Cruz. And I am driving a big, used silver Volvo station wagon, one bought just a few weeks before. My dear friend and colleague Kate Darling is in the passenger seat helping with Mapquest directions. We finally arrive safely at our destination, the first ever Science Studies creative writing workshop, organized by Martha Kenney and held at the University of Santa Cruz.

Soon after arriving at the workshop space, we found ourselves having lunch with much admired feminist scholar Donna Harraway. It was beyond lovely. Kate and I shared about our drive up. Donna joked that people in Santa Cruz often say that the road keeps those they don’t want out of Santa Cruz! In between bites of salad I laughed, not only because this was funny, but because it was probably true. I laughed out of relief as well, not believing we actually made it up that long winding road.

Our assignment prior to the workshop was to write a creative piece inspired by our scholarship. I was thrilled by the possibility of combining, intersecting, and interweaving theoretical questions I had with poetry/poetic form. At lunch I wondered what the feedback process would be like for the cross-genre works written for the prompt.

I’m a doctoral candidate in Ethnic Studies and New Media Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, and my interests includes the intersections of science, technology, and race. But I’m also a poet and new media artist with similar concerns. I like intersections, interventions, and mutations.

At the time, I was reading Aram Saroyan’s collection of minimalist poetry from Ugly Ducking Press. Simultaneously, I was working through Hsuan Hsu and Martha Lincoln’s co-authored article on the exhibit Body Worlds, while engaging with an online HASTAC Scholars forum (an amazing virtual new media collective) on Bodies + Body Worlds. I was concerned about the ethics of the exhibition, as well as the elision of issues of race and transnationalism in discussing Bodies + Body Worlds. When the opportunity to participate in the Science Studies creative writing workshop arrived, I signed up and wrote an early draft of “Materials” as an experiment. I hoped to delve into the questions (personal, political, intellectual) I had around the topic.

“Materials” is a special poem/new media/theoretical piece for me because it is my first attempt to merge the three “languages” in which I am actively engaged. How do they look together? How do they trouble ideas of poetry and theory? How is one supposed to read “Materials?” I have no idea and I like it that way.

“Materials” travels.

When preparing for the workshop at UCSC, I worked on an early draft of “Materials” during a long Bubble Tea Date with poet Jai Arun Ravine. I remember showing Jai the poem. Ze liked it, the center column the most. I continued writing the piece.

Then “Materials” was workshopped at UCSC with Martine Lappe, Karen De Vries, and Donna Harraway in an incredibly generative dialogue. Revisions were made. Their insights were honored and held within the poem.

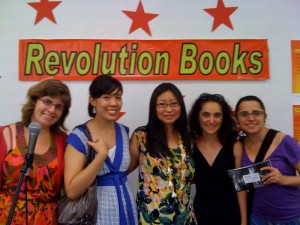

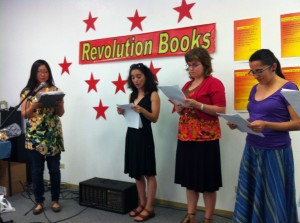

A few months later, the poem was performed at Revolution Books in Hawai’i. I read with dear friends and much admired poets Craig Santos Perez, Brandy McDougall, and Janine Oshiro. I was in Hawai’i for the UC Humanities Research Institute Seminar in Experimental Critical Theory (SECT), and serendipitously arrived just in time for the publication of my first chapbook, Yellow, by the University of Hawai’i-based Tinfish Press. Psychic convergence? Or poetic convergence? Perhaps both.

At the reading, my piece was a group performance. I asked a few feminist techno-science scholars to mutate into feminist techno-science poets and read “Materials” with me: Amy Shen, Jennifer Beth, Martha Kenney, and Tania Pérez-Bustos.

Though the act of writing a poem is often done in solitude, we do not write alone. Influences, settings, mentors, colleagues, books, news articles, emotions, and memories all flow into your bloodstream through the soft parts of your fingers. And some poems are not meant to be read alone but together.

+

In 2009, I presented with fellow Kundiman poetas at “Advancing Feminist Poetics and Activism: A Gathering” convened by Belladonna. During one of the sessions, I naively asked poet Ann Lauterbach, “What is the difference between poetry and theory?” She answered, “It’s not as different as they try to make you believe…”

That answer stayed with me and, I believe, enabled the writing of “Materials” two years later.

In April 2012, at the second iteration of the Science Studies creative workshop (now called Mutated Text), poet Cecil Giscombe spoke on poetry. After judging several poetry contests this year, Cecil shared that many of the judges’ debates included the accusation “that’s not poetry.” Cecil said, “When they say it’s not poetry, you know it is.”

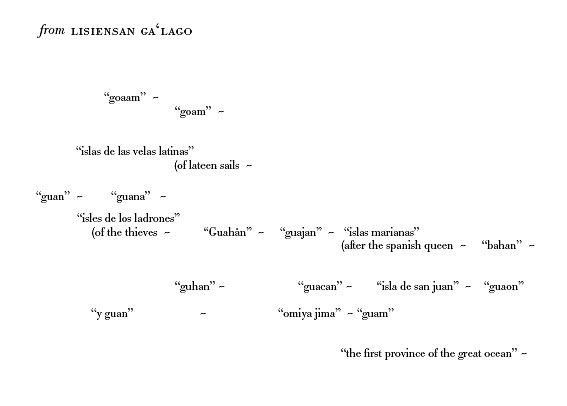

I suppose the process of writing “Materials” was an attempt to push the boundaries of poetry. Something my favorite poets, such as Cecil, Craig, and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, all do so admirably and politically in their work. Let’s take one of Craig’s maps for example, “from lisiensan ga’lago” in from unincorporated territory [hacha]:

The imagination is an Oceania of possibilities. The blank page is an excerpt of the Pacific, a blank map haunted by story. Each word is an island. The visible part of the word—its textual body—is where we live. The invisible part of the word is the submerged mountain of meaning. Words emerging from the silence are islands forming—phrases are archipelagos. The space between is defined by waves and currents.(Craig Santos Perez, The Poetics of Mapping Diaspora, Navigating Culture, and Being From (Part 5))

On our drive up to Santa Cruz, I had no idea my old car was dying. In a few weeks that car would break down—a typical occurrence for a poor graduate student and poet, I suppose. But I come back to that Santa Cruz Road because I want to think about roads and writing poems.

Sometimes the road to a poem is a straight shot. Or it’s a long stretch of highway whose horizon never seems to end. Or it’s a dangerous road that winds around and around, the kind of road on which you just need to continue on and on. Like my first trip to Santa Cruz: even though you’re not sure if you’ll get there, you just trust that your used car is going to last and take you where you’re supposed to be.