Lee Herrick is the author of This Many Miles from Desire (WordTech Editions). His poems have appeared in many literary magazines and anthologies, including The Bloomsbury Review, ZYZZYVA, Highway 99: A Literary Journey Through California’s Great Central Valley, 2nd edition, and One for the Money: The Sentence as Poetic Form, among others. Born in Daejeon, South Korea and adopted at ten months, he lives in Fresno, California and teaches at Fresno City College and in the low-residency MFA Program at Sierra Nevada College.

***

LR: One of the themes in This Many Miles from Desire that stood out most to me is the notion of the liminal space. There is, for example, the dream space of such poems as “Three Dreams of Korea: Notes on Adoption,” the physical space of travel—of being in between here and there, linguistic space, and also spiritual space. Could you talk a bit about how you envisage this relationship between space and liminality in your work?

LH: When I wrote This Many Miles from Desire, I had only been back to Korea once since being adopted. My return was very brief–two days–and that return formed “Korean Adoptee Returns to Seoul.” Since then I have been back for longer periods of time, but the vast majority of This Many Miles from Desire was written in a time where Korea was one large, complex question in my mind. I did not know most of the major details of my early life: the day I was born, who my birth family was (I still don’t), or even what cities like Seoul or Daejeon looked like. In one sense, I felt fully alive, but in another sense, there were so many uncertainties. For example, I do not know my family’s medical history, so that contributed to the sense of liminality to which you refer. My adoptive family is my family, and we are very close. But national origins are vital, so much of the book explored that territory. You can see it in some of the poems. I was on a journey, literally traveling through Latin America and Asia and piecing together remnants of the world to reduce the gaps between my early years and who I had become.

“Three Dreams of Korea: Notes on Adoption” was a breakthrough for me both as a person and as a poet because it was one of the first poems I ever wrote about my adoption. The important part of the process was when I discovered Richard Hugo’s The Triggering Town, essential reading for any poet, in which he problematizes the often used teaching phrase, “write what you know.” I was rather paralyzed, then, because I did not know (about my birth country, my birth family). I couldn’t reference the streets, the food, the people, the sounds of my country. So it was a major turning point for me when Hugo says we should invent. You do not necessarily have to “know” (literally) to write the poem. We can imagine. And so I did. In “Three Dreams of Korea,” I even imagined the dreams. I never had those three dreams. I created them for the poem’s sake. It was incredibly liberating. We write in the direction of discovery. Maybe we float in and out of various states of knowing, and our poems represent that floating.

LR: Many of the poems in This Many Miles from Desire reflect your extensive travels in Latin America and Asia. How did being surrounded by languages other than English influence your poetry during that time?

LH: Being surrounded by other languages during the writing of This Many Miles from Desire gave me a deeper understanding of the ways we calibrate individual experience, historicize it in a personal context, and how cultural and linguistic nuances impact our lives, and in my case, my poems. But I’ve always been interested in sound. So it was perfect—free-writing in a Bolivian plaza, a Korean cafe, or market in Oaxaca, while hearing the languages swirl, the bustle of the local machines, the instruments and the musicians. A fair amount of This Many Miles is about the music of other countries. If poems need air, breath, sound and timing—what better way to bring this to your poems than by bringing it into your life through travel? That’s what it did for my poems—expanded what they could become. I didn’t plan for it to happen. I just absorbed those countries, and they became a part of who I am and what I write.

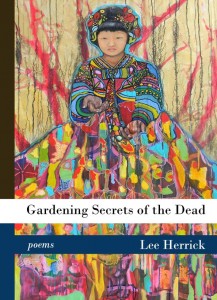

LR: What can we expect from your forthcoming book, Gardening Secrets of the Dead? In what ways does it differ from This Many Miles from Desire?

LH: Readers can expect new perspectives on some of the themes I have explored before: grace, family, Korea, and (un)certainty. Gardening Secrets of the Dead feels like a very different book, though. To me, it is more political, and the poems also consider the dead and their impact on us, the living. There are poems that reference Gauguin and Van Gogh, Ho Chi Minh, the Korean composer Isang Yun, as well as poems of homage to people I have known, including the Korean adoptee Julia Mendelson and others. There are also some poems about the end of love and its rebirth. I also hope readers will notice some attention to craft. Some of the poems in Gardening Secrets of the Dead are darker than the first book, but as with any shadow, light is required. I hope the book is full of light.

LR: What was your process like while writing Gardening Secrets of the Dead? Can you describe the life cycle of a poem or two that you found particularly compelling to work on?

LH: I can talk about “Fire.” Here is a poem whose initial idea was born about ten years ago when I was in Viet Nam. I saw a small, old, rusted blue car near a museum. It was the car that transported Thich Quang Duc to the busy intersection in Saigon in 1963, where he then got out of the car, sat in the lotus position, had gasoline poured over him, and then he was lit on fire: self-immolation. I was stunned to learn more about him, and seeing the car was unforgettable. I saved that image in my mind for years.

Last year, I began to draft a poem called “Fire.” Its initial impulse was to be structurally organic and fluid, like fire, and that remained constant through the revisions. The title also did not change, ultimately. But the drafting and revising of “Fire” was a challenging process. I struggled with focus and how much to let side-roads of the poem wander. One spark off a fire can cause another fire, if you will, and I struggled with that—knowing which of the poem’s sparks should be fanned and pursued, while trying to maintain the central fire or the central focus of the poem. I also struggled with the ending and the shape—some of the normal challenges that arise for me. I revised the poem substantially for about one year. As you might guess, it felt very good when it was “done.”

LR: You have spoken of your role as a professor as a process of “drawing the authentic parts of the self and the poem.” Can you elaborate on this: what are the authentic parts of the self and the poem and how can a professor help to draw these aspects out in his or her students?

LH: I think a professor serves many roles. To the extent that poetry can be taught, I think it is important to ask students to consider what their poems want to utter or be, and how purely the poem is achieving that state. This may come through any number of forms, techniques, and revisions, and I also believe it involves the poet being ready to acknowledge some truths, take risks, and “convict thyself,” as Dostoevsky advises. The young poet may or may not be at a point in her life where she is able to access these personal, authentic places. It is a process. But you have to dig. Get messy. The poem may then establish some roots. I don’t know if I have answered the question per se, but it takes a while in the classroom. It is far from therapy, but it has to be a safe place where rigor and risk are involved.

LR: In 1996, you founded the literary magazine In the Grove. What has your experience as an editor taught you about poetry, either in terms of your own writing or your understanding of how the industry works?

LH: I learned so much editing In the Grove. First and foremost, I appreciate the hard and often thankless work of good editors. I also understand the satisfaction an editor feels when her work is published. For example, In the Grove—which is on hiatus at the moment, as I have turned my time and attention to my own writing—published the title poem of the late, great Andrés Montoya’s book, the ice worker sings and other poems. We published Pulitzer winners alongside first-timers in print. I liked how you could shape an issue to your own tastes. I liked how you could take risks.

For beginning writers it is valuable simply because you can learn so many of the current do’s and don’ts, which do matter, for better or worse. Could a ground-shifting poem be written and submitted on a Peet’s napkin? Probably. Would it be a miracle if it made it out of the slush pile? Probably. There are so many things like this that one can learn by being an editor. It’s invaluable in some ways. Knowing as much of the spectrum as possible can probably only help. Maybe this is why the country’s best chefs who train at the Culinary Institute of America have to do a rotation as a server (not that an editor is a “server!” But you get the gist, I hope). Knowing your audience is helpful in many different situations, including writing poetry. If you have ever put together an issue from the editorial side, you will know why response times can take so long. Be patient.

LR: Speaking from your perspective as a writer, editor, and professor, what are some of the most interesting trends that you’re seeing right now in contemporary Asian American poetry?

LH: I don’t know about trends, and to be honest I have never been that interested in following them—but I know what you mean here and I appreciate the chance to say what I find interesting and/or valuable in contemporary Asian American poetry. I admire the Hmong American emerging poets like Mai Der Vang and Andre Yang with roots in Fresno, the Berkeley poets like Margaret Rhee and Barbara Jane Reyes (talk about a visionary), the wonderful impact that Kundiman has had on contemporary poets, the wide-reach of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, and some of the emerging Hapa voices like Matthew Olzmann. I’m also very happy to see more poets, such as Tina Chang, Sasha Pimentel Chacón, Ken Chen, and Ed Bok Lee, acknowledged with laureateships or major awards. Have you read their books? They’re extraordinary. I had the honor of reading for a national poetry contest recently, and I can also say how impressive other young writers are—two of my many favorites are Leah Silvieus and Eugenia Leigh. And I must mention the work of my fellow adopted Korean poet, Sun Yung Shin, whose groundbreaking new book is Rough, and Savage. Have you read these writers? Their work is stunning.

One “trend” I would like to see develop more is remembering, anthologizing, and respecting some of the poets whose careers were established earlier but remain vital: Amy Uyematsu, Li-Young Lee, Lawson Fusao Inada, and poets of their generation. There are many exciting new voices. But let us enlarge, expand, and remember as we progress, and not let important voices be devalued in the process.

LR: Has becoming a parent changed your writing and if so, how?

LH: It has changed my writing in that my life has become more full, and for that I am deeply grateful. Time management gets important, as I have to pick my spots when and where to write. Sometimes, especially when the child is an infant or a toddler, you may want to write but feedings or diapers take precedence. I am a poet, but I am a father first. First and last. It is my greatest joy. When I can, I shape the poems in my head.

LR: You have said that you like to listen to your iPod during your morning writing sessions. What have you been listening to lately? Do you find that music influences your poetry, and if so, how?

LH: Music is important for me—more so in life than specifically in my writing, although as I write this, I have my headphones on. Let me answer this question like this:

Some vinyl albums I own: The White Album (Beatles), Sumday (Grandaddy), Pearl (Janis Joplin), Greatest Hits (The Who), Houses of the Holy (Led Zeppelin), Terror Twilight (Pavement), and War (U2).

Here are the Pandora stations on my iPhone (some of these are my fiancé’s stations; your readers can imagine which ones are hers and which are mine):

Bon Iver and St. Vincent, Ratatat, Kaskade, Thievery Corporation, The Black Keys, Stone Temple Pilots, Jack White, The Rolling Stones, U2, Feist, Alice in Chains, Nirvana, Miles Davis, The Kills, The Cure, The Beatles, Janis Joplin, Violent Femmes, Soundgarden, Florence and the Machine, Explosions in the Sky, Archers of Loaf, The Shins, Fugazi, Beauty Pill, and Against Me!

“You are,” as T.S. Eliot reminds us, “the music while the music lasts.” I cannot imagine life without music. It impacts my life immensely, and so by extension, sure, music affects my writing immensely. And, full disclosure: my love of the Beastie Boys will most likely never die.

LR: Can you tell us a bit about what you’re working on now?

LH: I am working on poems that may find themselves in my third book. I am always working on an image. I am often working on noticing grace. I also have some other ideas swirling around in my head—some collaborations, some experiments, and some—maybe, just maybe—some explorations into a memoir.

One thought on “A Conversation with Lee Herrick”