This season, we’re privileged to welcome Eugenia Leigh to our team as guest editor. Eugenia is the author of Blood, Sparrows and Sparrows (Four Way Books, 2014) and the recipient of fellowships and awards from Poets & Writers magazine, Kundiman, Rattle, and elsewhere. She’s previously served as poetry editor at Kartika Review and Hyphen magazine, and she’s also a past contributor to the magazine and the blog here at Lantern Review. As Eugenia will be working closely with us to curate and produce the magazine this season, we thought we’d take a minute to help you get to know her. Read on to learn about some of her favorite reads of 2020, the Word document she keeps on her desktop for inspiration, what “Asian American futures” means to her, and more.

LANTERN REVIEW: How did you come to poetry?

EUGENIA LEIGH: Like many children from dysfunctional, abusive homes, I was taught to lie about my life as a child. Given that my parents were also pursuing ministry work in Korean Christian churches, the lying was even more imperative to maintain the illusion of our nice family. This made for a pretty lonely childhood. In junior high, an English teacher gave us the assignment to adopt a poet of our choosing, create a report, and recite one of their poems from memory for the class. I chose Anne Sexton randomly with no knowledge of who she was, and I recited a posthumously published poem, “Red Roses”—a poem about child abuse, thinly veiled. I still remember reciting this poem to the class and feeling the electricity of being able to tell at least one small truth in this artful way. After discovering Anne Sexton and the confessional poets, I often turned toward poetry to process and work through a lot of my ongoing childhood trauma during my teenage years. I’ve grown comfortable admitting that before poetry became an “artistic pursuit,” poetry was first an important coping mechanism and survival tool for me.

LR: What’s something you wish you had known when you were just starting out as a writer?

EL: When I was a senior at UCLA, a dear older white male poet announced to our poetry workshop—after critiquing one of my poems—that “if you’re forty and you’re a poet, then you’re a poet. But if you’re twenty and you’re a poet, you’re just twenty.” I’m nearly forty now, and I can still recall the humiliation of that statement, which stayed with me longer than it should have. When I was starting out as a writer, I wish I’d known to block out the many toxic voices I allowed into my ever-anxious, ever-insecure mind. I wish I’d believed in myself and in my writing, and I wish I’d applied for every chance to learn, grow, and showcase my work. I wish I’d had Michelle Obama’s voice to quiet my imposter syndrome by saying, “I have been at probably every powerful table that you can think of, I have worked at nonprofits, I have been at foundations, I have worked in corporations, served on corporate boards, I have been at G-summits, I have sat in at the UN; they are not that smart.”

LR: What interests or obsessions are driving your work right now?

EL: A few years ago, I was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder and complex PTSD, and this has fueled a new interest in the ways mental illness intersects with intergenerational trauma, especially within Asian American (and more specifically, Korean American) families. As a new parent, I’m also interested in narratives that upend the curated, Instagrammable stories of parenthood and have been a little hellbent on putting the uglier bits of this life into my newer poems.

LR: What are some of your favorite poetry collections of the moment?

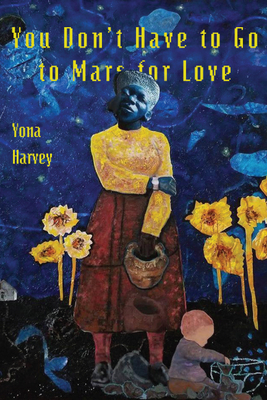

EL: A few favorite poetry collections from 2020 that I can’t stop thinking about or recommending to people: John Murillo’s Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry, Leila Chatti’s Deluge, Yona Harvey’s You Don’t Have to Go to Mars for Love, and Choi Seungja’s Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me (translated by Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong). I’m also pretty obsessed with these 2020 nonfiction books by Korean American poets: Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings and E. J. Koh’s The Magical Language of Others—both of which made me cry multiple times. I feel actual gratitude that all these books are out in the world.

LR: What’s one writing ritual or self-care practice that helps sustain you?

EL: I keep a Word document on my desktop called “Anthology of Quotes”—an ongoing collection of inspirational quotes to keep me going when I want to quit. I read through it when I feel unable to continue writing. A lot of Audre Lorde in there, some philosophers, even some from contemporary actors or anonymous quotes floating around Instagram. And one Bible verse (though I’ve completely forgotten its context now): “They were all trying to frighten us, thinking, ‘Their hands will get too weak for the work, and it will not be completed.’ But I prayed, ‘Now strengthen my hands’” (from the book of Nehemiah, chapter 6, verse 9).

LR: In keeping with this season’s theme, what does “Asian American futures” mean to you?

EL: When I think of “Asian American futures,” I imagine new generations of Asian American poets putting to paper what our parents, grandparents, and ancestors could never bring themselves to say. I envision poetry that refuses to wait around for permission. Poetry with an urgency that matches the times. Poetry that cost the poet something to write.

* * *

We hope you’ll join us in welcoming Eugenia to our editorial team for the season! For more from her, check out her website—or head on over to read our previous interview with her, right here on the LR blog. (And don’t forget to send us your own takes on “Asian American futures”! Our regular open submissions period closes on February 11th.)

* * *

ALSO RECOMMENDED

Yona Harvey, You Don’t Have to Go to Mars for Love (Four Way Books, 2020)

Please consider supporting an indie bookstore with your purchase.

As an Asian American–focused publication, Lantern Review stands for diversity within the literary world. In solidarity with other communities of color and in an effort to connect our readers with a wider range of voices, we recommend a different collection by a non-Asian-American-identified BIPOC poet in each blog post.

One thought on “Six Questions for 2021 Guest Editor Eugenia Leigh”