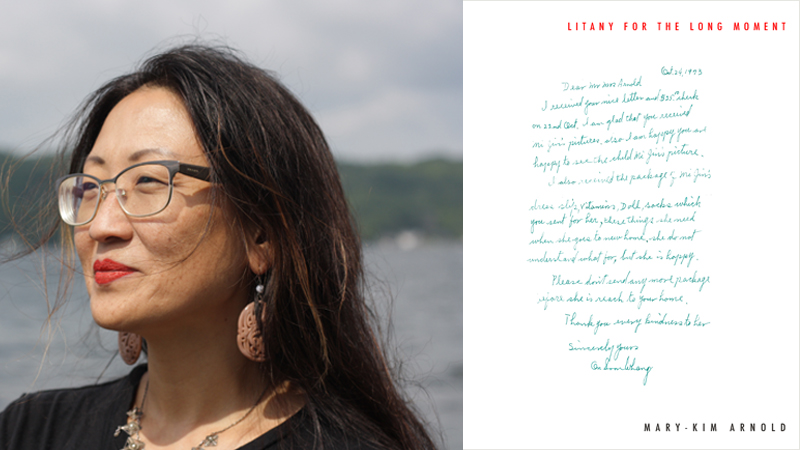

Recently, we had the privilege of speaking with poet, essayist, and visual artist Mary-Kim Arnold about her book-length essay, Litany for the Long Moment (Essay Press, 2018), included in the Entropy Best of 2018 Nonfiction Booklist and as part of the Brew and Forge Book Fair. Litany is a luminous work that yearns for lost parents and homeland, that refashions aesthetic and historical lineage out of an obscured past. Arnold shared with us her reflections on dominant narratives of transnational adoption, the limits of language, and the process of placing oneself under scrutiny. An excerpt of Litany can be found on AAWW’s The Margins.

* * *

LANTERN REVIEW: You title your book Litany for the Long Moment after photographic processes and begin the essay with reflections on Francesca Woodman, who, as you note, transformed photography into a medium for self-discovery and self-destruction. What was photography’s role in your process of composing the book, and how do you view its relationship to language?

MARY-KIM ARNOLD: I was interested in the handful of photographs of myself as a child in Korea—a self I could not remember and would never know, a self who really no longer existed. So I knew I wanted to incorporate those photographs in some way, to examine this ghost self who haunted my life as I knew it.

I was taken with the idea of the long exposure and how that process could show motion over time, but the effect was a kind of blurring or obscuring of the subject. I think this is a bit of a metaphor for the life of the adoptee. For me, as a transnational adoptee raised by white parents, the interruptions in family lineage were made visible. My Koreanness amid their whiteness was always visible, always subject to scrutiny, always asked to account for itself.

Despite that constant scrutiny, there is something central to the life of the adoptee herself that remains unknowable. Being visible is not the same as being seen, not the same as being known or recognized as a whole person. Under the persistent gaze, the adoptee becomes flattened, a kind of symbol, not fully human, but a representation. Ultimately, Woodman’s work and the photographic process she was using toward the end of her life provided a starting point for me to consider the role of the female artist, writer, subject. There is a way in which the female artist is simultaneously both subject and object. Woodman’s photographs and the critical writing about her work gave me language to think about myself in relation to the photographs of myself.

IH: In the book, you observe and resist romanticized adoption narratives—from the dream of maternal return to a dissonant press release from the Korean government that presented adoptees as “a precious resource for the international development of Korea.” How did writing Litany shift your own meditations on absence and separation—on both the personal and national-historical levels?

MKA: I think subconsciously, I have always wanted a romantic reunion, too. I think there’s a part of me that has always thought one day, something would happen, things would fall into place, I would have something handed back to me that made sense.

Through the process of writing the book and over time, I have come to recognize that there is no romantic reunion possible. The fantasy of reunion for me, as an adoptee, has been perhaps a kind of self-imposed exile from the realities and complexities of the life I have built for myself here. Recognizing this does not erase or deny the trauma of that initial separation. Nor does it obviate my grief for the life I might have had, the family I might have had. But it perhaps makes certain realities of the life I do have more knowable. If the reunion fantasy made me brittle, inflexible, closed off to the richness of my real life, letting the fantasy go has perhaps allowed me to be more porous. I can take in and absorb more of what is real and possible in my life.

As for the national-historical level, contextualizing my personal story within the larger political and socio-cultural intricacies of US-Korea relations lifted a kind of burden of personal responsibility and shifted the focus to the policies, systems, and institutions that made abandonment and transnational adoption the desirable course of action. I think the dominant narrative around Korean adoption in my generation focused on individual failures and choices—the single woman who was too poor to keep a child, the young woman who had an affair with a married man, the child who was born with health complications too serious for a poor family to contend with. And for the most part, what was absent from the discourse around adoption was the failure of social service infrastructures, systems and policies that made the relinquishment and export of a nation’s children seem not only an acceptable but a desirable course of action for Korea in which families in the US were encouraged to participate.

IH: I was struck by your reclamation of “taking life” as “taking it in”—an act that not only reasserts your own agency to write into rupture but also stakes out territory for Francesca Woodman, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, and Lady Hyegyong, among others. What is the connection between reclaiming the self’s history and body and reclaiming those of another?

MKA: I like to think that the more we try to tell the truth of our experience, the more we make space for others to do the same. I think the increasing numbers of narratives of adoption written by adoptees maybe pave the way for others—so that adoption can be understood as having more than one narrative arc, as being more than the dominant narrative. I think that narrative has historically positioned adoptive parents as selfless saviors and adopted children as forever indebted to them. Perhaps adoptees whose own experience of adoption was not like this, [and/or] did not feel like this, can find permission to tell their own stories, too.

IH: In Litany, you quote Lady Hyegyong: “Many things were hard to speak of . . . and I have left them out.” What are the differences between the excisions involved in self-portraiture versus those required in documentary?

MKA: Lady Hyegyong’s memoirs allowed me to think about memoir and self-reporting as a political act. She claimed the truth of her experience, even though it conflicted with the accepted, official record of courtly life. In self-portraiture, I don’t think I feel the same level of accountability to telling the whole story as I might in documentary. I’m not attempting to talk about the adoptee experience in general; this is just my own story, my own experience, as best I can attempt to represent it at this particular moment in time.

IH: In Litany, you write, “I fear this is asking too much of syntax.” What do you understand as the intellectual and bodily limits of language?

MKA: I wanted language to be this kind of bridge between my Americanness and my Koreanness. I wanted to be able to claim and inhabit Koreanness through learning this language as if uttering words or phrases in another language gave me a sort of bodily access, bodily knowledge to Koreanness. But learning a completely unfamiliar language is very difficult as an adult, and some of the fragmentation, some of the silence arises from that gap—the desire to lay claim to Koreanness but the inability, at the most basic level of language, to do so.

All the same, I think we’ve become very removed from knowledge that is not purely discursive and bound by language. There is knowledge that resides in the body, in memory. I think there is a limit to what the body can take in and process through language. I was thinking about the ways in which language is inadequate, particularly in grief. Silence is its own strategy, has its own textures and weight.

IH: How do you step back to gain critical or emotional distance from your research and writing?

MKA: It takes time, I think. Just a lot of time. Lots of stepping away, putting it aside, coming back to it. It was an intense process, but it was also exciting, artistically, to set myself these little problems to solve.

I am reminded of a line I came across in a poem years ago. I don’t remember the context of it, but it was something to the effect of waiting for the words to have soaked up enough. That feels like part of it. Letting the language steep and become its own thing. At some point, it wasn’t as directly, as personally, about me. It was about trying to tell some kind of story and maintaining some sort of devotion—to the story rather than to me and my own feelings.

IH: What has been most challenging about placing yourself and your life under poetic scrutiny?

MKA: I was concerned about how my family members might react—my sister; my aunt (who is my mother’s sister); and even, to a lesser extent, my own children. My family went through a lot of trauma during the period of time I cover in my book, and I did, at certain times and over certain details, feel very protective of us all, of who we were then, of what we were living with.

IH: In your interview with Essay Press, you talk about the various paths of research you took to compose Litany—from Lady Hyegyong and courtly life to US involvement in Korean adoption. What parts of your process for Litany do you want to extend into future projects? How has the process for your second, forthcoming poetry collection, The Fish and The Dove, been related to or different from your process for Litany?

MKA: Some of the research led me to the Korean War, and while I was watching a lot of war documentaries, this notion of enemy and loyalty started taking shape. In that context of war, these questions—who are you, where are you from—demanded a kind of reckoning, a kind of accounting for the self in a public way that’s made visible for approval. Several of the poems in The Fish and The Dove attempt to address divided or complicated loyalties.

In that collection, I have also been thinking about particular kinds of language—institutional language that purposefully hides itself and obscures truth in an attempt to deny accountability. Statements like “mistakes were made” and “lives were lost” purposefully obscure the subjects, the actors. Who made these mistakes? Who took these lives? I am trying to think about and give breath to the casualties of institutional language.

IH: You similarly explore lineage, adoption, and Korean identity in visual art—as with “(Re-)Dress: One for Every Thousand” or “Guidelines for Arrival and Transfer.” Could you talk a bit about how visual art and writing inform one another in your practice and research? How has each medium allowed you to discover, or come to terms with, different aspects of identity?

MKA: I think for a very long time, I had resisted the idea that the fact of my adoption—the rupture of it—was as significant as it was to my sense of self. When I finally was ready to take it on in a meaningful and direct way, it was like floodgates opening. Suddenly, there were all these questions I had that I had only previously considered in superficial ways. Like: Why did this happen? Not just to me, but to 200,000 Korean children, 200,000 families. I wanted to think about that scale. Thinking about that scale allowed me to think beyond the individual level—no longer were the questions: What were the circumstances of my family? Why did my mother feel as though this was the choice she had to make?—the emphasis shifted from the individual to the systems. What was happening in the interconnected political, social, economic, and cultural conditions in the US and in Korea that made this unprecedented separation of families possible? So, I suppose if Litany for the Long Moment is focused more on my own individual experience, perhaps “Re-Dress” is a way to think about the larger forces at work.

IH: You are currently a visiting lecturer at Brown University. How does your emphasis on experimental, interdisciplinary work influence your pedagogy?

MKA: I think of formal choices as necessarily political. The decision to make something “accessible” or invisible or easy to read, where the underpinnings of language can be overlooked so that the content is foregrounded—that’s a particular kind of choice and relies on a set of assumptions and internalized values. I talk a lot about the kinds of stories that resist a narrative line. Who gets to tell stories with neat conclusions? Whose stories are interrupted, silenced? When we talk about a conclusion in an essay, a resolution, who is that resolution for? I talk about writing—and mostly I’m dealing with creative nonfiction—as exploratory rather than as persuasive. This shifts the emphasis from conclusion to inquiry.

* * *

Mary-Kim Arnold is the author of Litany for the Long Moment. She is a poet, writer, and visual artist based in Rhode Island, where she teaches at Brown University. Arnold’s work appears in The Georgia Review, Hyperallergic, and The Rumpus, among other publications. She is currently working on a novel, Nine Men’s Misery, and a poetry collection, The Fish & The Dove (forthcoming from Noemi Press in 2020). More of her work can be found on her website: mkimarnold.com