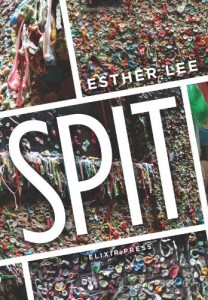

Esther Lee has written Spit, a poetry collection selected for the Elixir Press Poetry Prize (2011) and her chapbook, The Blank Missives (Trafficker Press, 2007). Her poems and articles have appeared or are forthcoming in Lantern Review, Ploughshares, Verse Daily, Salt Hill, Good Foot, Swink, Hyphen, Born Magazine, and elsewhere. A Kundiman fellow, she received her M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Indiana University where she served as Editor-in-Chief for Indiana Review. She has been awarded the Elinor Benedict Poetry Prize and Utah Writer’s Contest Award for Poetry selected by Brenda Shaughnessy, as well as having been twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Ruth Lilly Fellowship, and AWP Intro Journals Project. Currently, she pursues a Ph.D. in Creative Writing and Literature at the University of Utah and lives with her fiancé, Michael, and their dog and three cats in Salt Lake. Starting this fall, she will begin teaching as an assistant professor at Agnes Scott College.

This April, we are returning to our Process Profiles series, in which contemporary Asian American poets discuss their craft, focusing on their writing process for an individual poem or poetic sequence of theirs. As in the past, we’ve asked Lantern Review contributors to discuss their process for composing a piece of theirs that we’ve published. In this installment, Esther Lee reflects upon the excerpt of her project Daughters of Celluloid that appeared in Issue 5.

* * *

(if his plate would not record the clouds, he could point his camera down and eliminate the sky)

—John Szarkowski

If there is a hegemonic familial gaze, imposing rigid familial ideologies, then mothers are most cruelly subjected to its scrutiny.

—Marianne Hirsch

Excerpts of this Process Profile are pulled from a craft talk titled, “Double Exposures: Photographic Fictions and Traumatic Memories” given at Virginia Tech. All photographic images are ones I’ve taken or borrowed from family albums.

Excerpts of this Process Profile are pulled from a craft talk titled, “Double Exposures: Photographic Fictions and Traumatic Memories” given at Virginia Tech. All photographic images are ones I’ve taken or borrowed from family albums.

My hope is to invite you into a constellation of influences—and mostly questions—I’m working with and exploring in this work-in-progress, tentatively titled Daughters of Celluloid. This constellation includes the works of writers and artists who meditate on, thematize, and/or employ photography, as well as those whose works investigate the complexities of trauma and representations, in particular, of trauma not directly experienced first-hand. So a kind of assemblage, if you will, one that is part wax, part string, part etched glass.

In Daughters of Celluloid, the narrator finds that her mother’s enigmatic past is pocked with speech, presented as fragmented anecdotes, suggesting recessed narratives of trauma and dislocation. To borrow a phrase from the French novelist and Holocaust writer, Henri Raczymow, memory is “shot through with holes” and underscored by potential absences of family photographs wherein large swaths of time and space have seemingly vanished, losing any semblance of continuity. As a result, the narrator finds herself attempting to photograph the mother, grappling with how the camera can both fix and unfix them. In doing so, they disrupt their unspoken ways of looking, complicating the myths of familial memory and, ultimately, searching for what Alison Bechdel describes in her graphic novel, Are You My Mother?, as a “mutual cathexis” between mother and daughter, wherein they can recognize each other’s invisible wounds.

Continue reading “Process Profile: Esther Lee Discusses DAUGHTERS OF CELLULOID”