Recently, I had the pleasure of talking with poet and professor Chen Chen about his upcoming poetry collection, Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency, and how he envisions the poems in this manuscript as rest, fuel, and a tool for writing through trauma. Read on to learn more about his other collaborative projects, his experiences writing in quarantine, and more. (For more on Chen Chen, check out our previous interview with him in conversation with Margaret Rhee.)

* * *

LANTERN REVIEW: Can you share with us a little bit about your upcoming second full-length poetry collection, Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency, and what inspired you to embark on this project? How do you think the current sociopolitical landscape has affected or complicated your work?

CHEN CHEN: At this point, pretty much all the poems are written and in their final form. There might be one or two more poems the collection needs. Of course, I thought I was at this close stage last year. And then I kept writing new poems. And those poems influenced revisions on older ones. That’s how it goes.

This second book explores some of the same subjects as my first: blood family, chosen family, immigration, sexuality, and how to be a person fully embracing every aspect of my experience and identity. The key difference between the first book and this one is now I’m examining these subjects from an older perspective, much more of an adult perspective—whereas before, I was interested in childhood and adolescence. I think Your Emergency Contact is a sadder and angrier book, and at the same time, a funnier one. That tonal shift or tonal deepening has a great deal to do with the current sociopolitical landscape. Writing in and about the Trump era has led me to deeper grief and outrage, as well as sharper humor. The humor is a coping device, but also a way into the difficult emotions.

There’s a shift in setting, too. Your Emergency Contact grapples with what it meant to reside in West Texas—as a PhD student, as a young teacher, as a queer Asian American in a very conservative part of the country, a particularly conservative part of Texas. Some poems look at gun violence and gun culture. There are poems addressing the Pulse nightclub shooting, which took the lives of people who were (for the most part) queer and Latinx. These were deeply complicated poems to write, as I didn’t want to speak for anyone else, yet I needed to engage and process my own sense of grief regarding this violence.

Ultimately, Your Emergency Contact is about an exhausted world, a world in which those I’ve relied on for care during crises are themselves experiencing calamity and depletion. The hope is that these poems create a space, however small and fragile, for the vital practice of recognizing marginalized people’s exhaustion. I’m tired. Those I love and those who love me are tired. Maybe these poems can offer some rest and some fuel.

LR: Can you share with us the origins of your collaborative chapbook project GESUNDHEIT! with Sam Herschel Wein? Why did you decide to embark on this project?

CC: Sam and I started writing collaborative poems years ago. Part of the genesis of our friendship was realizing we had many shared poetic sensibilities. We both love humor and play. We’re both obsessed with pop culture and queer culture. It felt completely organic to write together. I’d send Sam a line over email, and he’d reply with the next line, and so on. These early attempts were not very good. But we had so much fun. We kept dreaming of a collaborative body of work. Eventually we decided that it would be a chapbook containing poems we had each written individually, plus a couple we wrote together in this trading-lines-back-and-forth fashion. Fun fact: originally the chapbook was called Scarves of My Gayborhood. (We might still use that title for something else!)

As we put the chapbook together, it became apparent that friendship would be one of the major themes—in particular, queer friendship and how we grew to be part of each other’s chosen families. Sarah Gambito blessed us with the absolute best blurb, which includes this perfect summation of the work: “these gorgeous poems hold high the cherished intimacy that is activated in deep friendship.” I love that verb, activated; it speaks to how my friendship with Sam feels—active, empowering, full of action toward true mutual growth. GESUNDHEIT! is an ode to working together, playing together, discovering together. Rather than eliding or flattening out differences, the chapbook celebrates how we’re distinct poets and people, while simultaneously celebrating the conversations between us.

LR: You are the coeditor and cofounder of literary journal Underblong. How has your role as coeditor and cofounder inspired and helped you in writing? What have been the biggest challenges? What have been the biggest rewards?

CC: Underblong is a labor of love and laughter and the longest FaceTime calls with my coeditor and cofounder, Sam. Recently we brought on a fantastic managing editor, Catherine Bai, who’s helping us stick to our goals and to a better timeline for assembling our issues. We also brought on five wonderful new readers, Aerik Francis, Albert Lee (李威夷), Angelina Mazza, Cassandra de Alba, and Juliette Givhan. We’re ecstatic to welcome these new team members, or “blongees,” as we affectionately call them, and one of our main activities this fall has been working to make sure everyone gets to know each other. We’ve already been so lucky to work with readers E Yeon Chang (장이연), Emma William-Margaret Rebholz (a.k.a. Billy), and Mag Gabbert. Mag also serves as our fabulous interviews editor. I just had to shout out the whole team because they’ve been integral to the journal’s success and ongoing vibrancy or “blonginess.” Each team member has expanded our notion of what the journal can be.

Sam and I started the journal because we wanted to do something different from what we’d seen in the literary landscape. We wanted a journal that wasn’t afraid to break with so-called “professional” conventions and decorum. We wanted a journal that embraced poems about butts, poems about glitter, poems that speak back to racism and imperialism, poems that listen deeply to urgent cultural currents, poems that reimagine the future and insist on a more livable now. We envisioned Underblong as a space not only for publishing work that we feel pushes the boundaries but also as a space for us, as editors, to be as wacky and imaginative as we need. I think this freedom is reflected in each issue’s editors’ letter, in the “what we like” page, in the call for submissions page, in the website design, in the response letters to submissions, and in the overall vibe of the journal. And we wanted, from the very start, to center the voices of queer and trans Black writers, queer and trans writers of color. With each issue, we try to deepen our commitment.

My role has inspired my writing in all sorts of ways. I’m inspired by the work we publish. I’m inspired by the conversations about submissions. I’m inspired by the cover art. I’m inspired by responses from those who read the journal. I’m blown away by the support and enthusiasm folks have expressed for Underblong. That’s the biggest reward: seeing how the work we publish reaches people. For instance, how often the poems in Underblong inspire others to write their own. Another giant reward is, of course, getting to publish work we completely believe in, especially poetry by lesser-known writers—and most especially to be the first (or among the early ones) to publish an exciting voice.

The biggest challenges all have to do with time management. I teach undergraduate classes and also work with MFA students. I have my own writing projects. I have time commitments when it comes to my beautiful partner and my beautiful friends. Sam and I started Underblong with the goal of publishing two issues a year. It’s been one issue a year, and we’ve always struggled to release issues when we say we’re going to. I’m hopeful that will change with this next issue (scheduled for December) and with next year’s issues.

LR: In other interviews, you’ve talked about being a manic reviser. Can you tell us a little more about your revision process?

CC: It’s taken me a long time, but I really have come to love revision, as utterly frustrating as it can be sometimes. I’ve come to see the challenge as an invitation to continue discovering something through the act of writing. I cherish the surprise of finding something out about myself or about the world—something strange and sparkling I couldn’t have known without writing that exact poem.

Often, a first draft is merely the skeleton of what the poem ultimately needs to become. I know there’s placeholder language I’ll have to replace with excitement. I know there’s flatness I’ll have to transform into a mountain full of swaying trees or a sea roaring with all its sea-ness. And most frequently, in my poem drafts, there’s humor that starts off as just a silly riff on a stray thought or as a jumping-off point—and I know I’ll have to make the laugh as necessary as the lament. I’ll have to find that balance between tickling and truth telling. But first, I try to give myself complete permission to goof off, to experiment, to generate and generate.

I usually overwrite and then pare away. I like having a wide field of material to work with; from the field I whittle things down to the row that’s most alive, then tend to each stalk, each bulb, each petal. Sometimes I overwhittle and then have to zoom out again, add back a detail I’ve cut, or write something fresher in its place. Maybe the poem actually needs to be a whole wide field and not just one row. The unpredictability can be maddening or glee inducing; I tend to oscillate between the two states while revising. A poem can start off as six pages, then shrink to one, then grow into three.

LR: How have you been engaging with writing poetry and the poetry community since quarantine?

CC: I haven’t written a lot of poetry during this time. Actually, I’ve been writing more prose. I was asked by Spencer Quong at Poets & Writers to contribute short essays for an online series called “Craft Capsules.” My essays have ended up being sort of unconventional—a weird mix of craft commentary and personal writing. That’s just how I had to write them. I guess I was getting tired of being asked to produce prose along the lines of neat, easily digestible article or column writing. I needed to break out of those boxes. Fortunately, Quong and Poets & Writers have been very supportive of me doing things more my own way. Quong has also provided immensely thoughtful editorial feedback on all the essays. These pieces would be such a mess without his critical input and super-smart line edits.

I was also asked by Swati Khurana to write flash fiction for a new series at The Margins, the online magazine of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. Though I think of the piece I wrote as basically a lyric essay or an extended love poem, it’s been really lovely to see folks read it as a flash story. My first fiction publication! And Swati, as an editor, was also incredibly generous and insightful with feedback.

It’s been scary, writing and publishing in a genre I’m less experienced with and comfortable in. I did study creative nonfiction in graduate school; indeed, during my PhD, it was my secondary genre. I love reading creative nonfiction of all types. But as a writer, I feel very much at home in poetry. Poetry, including prose poetry, feels like how my brain works. Straight-up prose feels like trying to walk around in someone else’s brain. Or like spending a week at someone else’s apartment. I’m intrigued and I learn a lot, but by the end of the week I’m eager, I’m more than ready to return to my apartment.

My literal apartment is where I’ve been spending most of my time this year. It’s been difficult, much more difficult than I anticipated. I thought I’d be sad but still fine since I’m an introvert. But I’ve realized that becoming a part of poetry communities over the last several years has turned me into a bit more of an extrovert. I need people. I need conversations with people who also wildly love this wild thing called poetry. In 2020 I’ve had many of those conversations over Zoom, and they’ve been nourishing—but still not the same as in-person interactions.

I miss the literal nourishment of sharing food with poets. The metaphorical nourishment of conversation alongside the food on the table is magical. There’s something about sharing a meal with fellow poets and talking not about poetry but about the food. I mean, poets have a special craving for words, and that comes out no matter the topic, though my favorite non-poetry topic is food. Or gay sex.

LR: You teach at Brandeis University. What is the most rewarding thing about teaching poetry?

CC: The most rewarding thing is getting to hear students say, “I didn’t know you could do that in a poem!” This exclamation has happened after reading Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic, with its two-act play structure and its use of sign language. It has happened after reading Mary Jean Chan’s Flèche, with its experimentation with formatting and its use of Chinese script. It has happened after reading Sarah Gambito’s Loves You, with its recipes as poems and poems as recipes. It has happened after reading Diana Khoi Nguyen’s Ghost Of, with its stunning triptychs of family photographs, body-shaped poems, and erasure poems with body-shaped cutouts. It has happened after reading Patricia Smith’s Incendiary Art, with its mix of documentary and surrealist poetics. Students come in thinking that poems have to look and sound a certain way. It’s such a fun honor to get to show students that poetry is a laboratory, and they get to be innovators, too.

For the final project in my poetry workshops at Brandeis I ask students to invent their own poetic forms. They always end up doing the most incredible things—playing with white space, with punctuation, with diction and syntax, with imagery, with typography, etc., etc. I’m always wowed beyond what I thought was my capacity for being wowed.

LR: In your interview with AAWW, you speak about finally realizing that queerness and Chinese identity can come together to form an intersectional identity. In fact, writing about these identities is central to your work. For me, also as a queer Chinese person, I find it hard to write about traumatic events tied to my identity. How do you go about approaching trauma at the intersection of these identities?

CC: I let myself write as slowly as I need to. Sometimes in graduate school it was hard to stick to a slow process because I had to turn in poems on a much faster schedule (though deadlines can also be helpful; they keep me from endlessly tinkering and staying in my own head). Ultimately, I believe that each writer has their own pace. And for marginalized writers, it’s important to question why one is writing about trauma. How much of that comes from a white gaze, from the expectation that one should be writing about trauma, about suffering? I think it’s crucial that one has one’s own reasons for writing about these subjects.

One of my main reasons is I want to examine the narratives that I’ve inherited—my father tells me one narrative for immigrating to the United States; my mother tells me another. I want to understand better why my parents have these different accounts. Another main reason is I’m invested in complicating the stories I’m used to telling about myself and my past. Why do I talk about my coming out to my family in this way? Why not another way? So the poems aren’t about constructing one neat picture of my experiences; they’re about giving myself a multiplicity of interpretations, a liberating complexity. Slowness is essential for writing this way. I have to first do some personal work, some deep emotional work, to process the traumatic events. Then I write.

Often it’s messy, and I do relive some of the trauma, but the poems can’t be a pure reliving of the trauma. If it starts to be that way, I have to take a step back. I have to take time. I have to slow down further and protect myself. I’m not interested in subjecting myself to remembering over and over the worst things that have happened to me for the sake of a white audience—for the sake of any audience, really.

Poems can be healing, but they can’t be the only form of healing I rely on. If I overrely on poems for my mental health and well-being, poetry becomes a toxic force. It’s similar to overrelying on a romantic relationship for all one’s needs. I need to take care of myself outside of writing, then step back in. For weeks I might write just one more stanza. For months I might work on other kinds of poems. For years I might have no firm idea of where a poem grappling with trauma is headed. I trust, though, that if I’m doing this for the right reasons, the right language will come.

* * *

Chen Chen is the author of When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities (BOA Editions), which was longlisted for the National Book Award for Poetry and won the Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry, among other honors. He has received a Pushcart Prize and fellowships from Kundiman and the National Endowment for the Arts. With Sam Herschel Wein, he runs the journal Underblong. He teaches at Brandeis University as the Jacob Ziskind Poet-in-Residence.

* * *

Also Recommended:

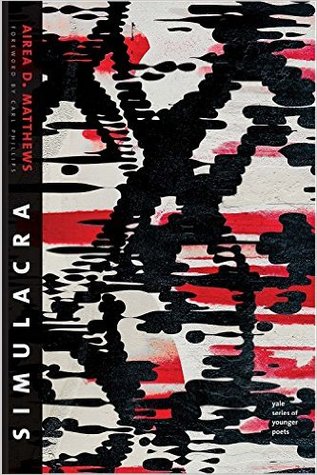

Airea D. Matthews, Simulacra (Yale, 2017)

Please consider supporting an independent bookstore with your purchase.

As an APA–focused publication, Lantern Review stands for diversity within the literary world. In solidarity with other communities of color and in an effort to connect our readers with a wider range of voices, we recommend a different book by a non-APA-identified BIPOC poet in each blog post.