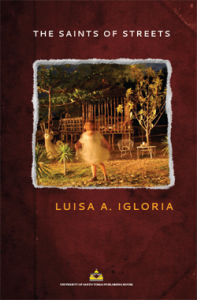

The Saints of Streets by Luisa A. Igloria | University of Santo Tomas 2013 | $17

“Hokusai believed in the slow / perfectibility of forms” (3), begins Luisa A. Igloria’s newest book of poems, The Saints of Streets. She has been writing a poem a day since 2010, a project archived online and from which this collection was born. Given how prolific she is, I could not help but find in these opening lines a reassurance that the poems collected here are not merely practice but are a practice. For perfectibility, the poem goes on to say, is “the way, // after seventy-five years or more, the eye / might finally begin to understand / the quality of a singular filament—” Indeed, this is a book of single filaments, and in these poems are so much delight and wisdom, often beginning in the mundane but nearly always spiraling inward to the sacred.

We see this spiraling quality first of all in the poems about place, which is one of what I’ll call three clotheslines bending with this collection’s poems: clotheslines, I say, because of the quality the poet gives to everyday activity, weighted with meditations even as it flutters in the wind. The place poems nod most pronouncedly to the collection’s title. In “Repair,” for instance, we begin in the present moment: “Almost at the alley’s elbow, I know the gate . . .” (9). Shortly after that, we move to the wistful past tense, each sentence beginning “There used to be” as a litany. Just as we first graze the alley as a kind of body, so does the speaker name the ghosts of objects as though in mortal lament, counting down structural losses, strippings, and repairs along with the absences of people. But the magic of this poem is in its concluding grammatical shift. See how, in the last three lines, the past tense makes way for something closer to the timeless:

across the south wall, even on the night the child

ran out the side door with bare feet, crying after the figure

disappearing halfway up the rise, beyond the street.

Line by line we move from a definite point in time (“on the night”), to an ongoing and simultaneous action (“ran out . . . crying”), and finally to an image marked by its remove from the rest of the action (“disappearing . . . beyond”). The medial caesura of each line helps us rhythmically, step by step, as do the definite articles. The final “disappearing” is a present participle, non-finite: not quite past and not quite present. And that last image of what is “beyond the street,” in its ghostly way, takes us through the longing into something even greater than the object of the longing, greater than the body of the street.

That’s what I mean by the sacred; that’s how Igloria’s poems spiral into it. In “Domicile,” the next poem after “Repair,” she tells us: “This is the only way / to think of home sometimes—before the blueprint” (10), for this poem too peels away at surfaces to that history of things we cannot see, and of “what we might bear / out of the ordinary darkness and the mud.” On the next page comes the title poem, “The saints of streets,” which gives us a history of place through names. It exposes geo-graphy—the writing of land—with narrative legends, but rather than merely explaining as if the speaker were a tour guide, the poem questions:

There used to be a waterfall

called Bridal Veils.In legend, a woman falls to her death.

(Why always on the eve

of nuptials?) (11)

The voice at first is factual, then seems wiser than the locals (“But there are no words for pole bean here”). But the voice really takes off when it becomes first-person plural, when we realize the emotional investment of this speaker who is connecting past with present, collective memory with individual memory, noticing the sound above “like bombs on rooftops” with, below, the “rows of stones under which all our dead lay sleeping.”

If continuity with the past (like the recurring motif of “strawflowers . . . that we called Everlasting”) occupies a large part of Igloria’s poetics, it may be unsurprising that many of these poems also deal with time’s divides in an immediate family; that is to say, poems of motherhood and poems of divorce. This is the second clothesline in the collection. In “Meditation on a Seam,” we get a personal history of the sacred, beginning with the early memory of two mothers—“she who birthed, and she / who raised me” (39)—making clothes for other women through the night, and of one morning when the stunning image of a wedding dress hung in a doorway of light while the women “knelt on the floor with pins / in their mouths, working round the hem.” Much later in time, we’re told: “In the dark, because of them I find / lost prayers in the tiny edging around buttonholes // in store-bought shirts.” There is a tinge of elegy in the poem, which skirts around “the gathered dust and tears” and yokes the image of seams (creases, pleats, edges) to reverence, prayer, closeness across time.

A few poems later, we come to “Horizon Note,” which at first seems occasional in its random observations until the speaker realizes that her tone, “unkind and full of remorse,” is coming from an unrelated memory many years ago, the moment of meeting “the man bent on marrying [her]” (46). She says, with a touch of wistful spite: “I could almost believe I was / meant for something greater than this.” Though the speaker is quite terse on the subject, the poem leads directly into the next, “Little Islands,” which is less oblique about “fifteen / years of marriage gone sour, a dried-up can of soda / someone left behind on the sand” (47). As we move forward in the collection with poems that touch on this subject, the speaker becomes more forceful, more stolid in her own shoes. In “What to Do with Suitors in the Courtyard,” Igloria, riffing on the image of Penelope waiting at home, writes:

. . . I’ve discovered something:

I wouldn’t have lasted a week with that loom.Faithless? Let me tell you something. I could’ve cleared

that courtyard of pseudo admirers, interested only

in what they could stuff in a sack. Annex meany way you want, but leave me alone. (67)

In “Manual,” at the time of another marriage, while answering her six-year-old’s question about relationships, the speaker yanks back her ex’s chauvinist metaphor for marriage, “A car has only one steering wheel” (69). Wearier and warier now, yet buoyant in the charm and joy of the scene, she cuts with a last line that disrupts the poem’s tercets: “But it helps if you know how to drive.”

This, and other poems of emancipation, are tracked and tempered by the presence of children. There is a fullness to the poet’s vision in this collection because, in addition to horizontal relationships (which might otherwise have resulted in poems merely of anger) and the upward relationship of reverence (which might have resulted in merely devotional poems), there is also the downward relationship to a next generation. In “Ziggurats there aren’t here, my sweethearts—” the speaker says: “I wanted to give you / keepsakes that wouldn’t tarnish: a wraparound porch, a swing, that / Jungian well cleared of debris at last . . .” (68). This relationship goes beyond the literal relationship to one’s children. Woven through this book is a delicate care-taking. The good intentions may not meet their consummation in the poems: “Instead,” continues the above, “I’ve understood no more, no less than this wild / hunger . . .” However, the intention itself is a mode of seeing, which is precisely what Igloria’s poetry offers best. That poem ends:

. . . But

don’t think this is mere lamentation or elegy. I’ve seen someone

come to the lake faithfully each afternoon with a small

bag of crumbs for stray animals, just because

affliction has such a desolate color.

Lastly, I see a clothesline of ghazal poems strung throughout the collection. The ghazal is an Arabic form of rhyming couplets with a refrain. It is a form which, like the sonnet, relies heavily on a volta just past the halfway point. In this volta lies the poem’s capacity to charge each repetition of a thing until it changes by some metamorphosis of feeling or understanding. For Igloria, in more than one instance, this is a literal change in the refrain itself—for example, in “Ghazal: Some Ways to Live,” the refrain of “live” morphs at the volta into “give” (51). In “Mortal Ghazal,” the first and most powerful of the set, a meditation on what is “everlasting” morphs at the volta into what looks in the sky to be “unrelenting” (33). As in Bishop’s “One Art,” the force of the poem is built up to self-revelation at the end, and direct address, where this unrelenting lyric in praise of the everlasting is shown, finally, to be itself mortal and deeply vulnerable.

Igloria’s ghazal poems are best when the naturally abstract refrain lines are moved and buffered by narrative force. Though the ghazal appears here as a formal practice of meditation, like rosary beads to quietly obsess over, as yet it seems an inchoate form for Igloria’s poetics—and with some of these poems it can feel like including “ghazal” in the title serves as a kind of explanation or apology for what ought to stand on its own.

As a whole, this is a book of joyful energy distilled in wistful images and questions. I look very much forward to Igloria’s next collection, which given her rate of writing must be hot on this one’s heels. I’ll end with some of my favorite lines, from “Brood,” a frenzied poem about a child running off or disappearing—several times—and the speaker finally contending, “[o]n faith,” with the wisdom of Rumi:

But tell me what happens, after the snake has made its way

up the trunk of the dead elm into a den of flickers, emerging later

with a new bulge sleek in its black belly—Except for the wind,and cries of birds that haven’t learned anything but account

for duty, nothing troubles the branches of the lilac trees. (27)

4 thoughts on “Review: Luisa A. Igloria’s THE SAINTS OF STREETS”