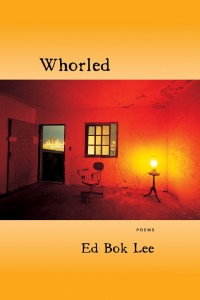

Ed Bok Lee is the author of Whorled, winner of the American Book Award, and Real Karaoke People, winner of the PEN/Open Book Award.

* * *

LR: After working in the fields of fiction and playwriting, as well as journalism, how did you come to poetry and how did you eventually come to compose a poetry manuscript?

EBL: I wrote a poem about God when I was four or five, then didn’t do much of anything, until I was seventeen, and started writing again. Sometimes I think people who love poetry wander around this world missing a certain layer of skin that others seem to naturally have. Whenever I write a poem, I suddenly feel completely fortified, with language. Language, word by word, forms a kind of extra layer of skin, and, for a while, things seem to make sense. I think it has to do something with an impulse to preserve some lesser-heard, lesser-lit kind of integrity out there in the world and simultaneously within, that you feel is being compromised.

And then, after a while, you have all these shed skins accumulated, and it’s time to de-clutter and turn them into a collection.

LR: Do you find that elements of journalism and playwriting filter into your poetry, and if so, how?

EBL: It’s the opposite. Poetry kept creeping into those forms. It’s probably a two way street, I’m not sure. What I do know is if there isn’t poetry, or a poetic quality, or a poetic mode of consciousness filling the vessel, whatever genre/form, boredom begins to creep in for me.

LR: In your first book, Real Karaoke People, music seems to act as metonym for the voices, language, and preoccupations of regular people. What was it about those voices and sounds that asked to be written in poetic form rather than as a play?

EBL: You write a line, which is the DNA of what a piece seems to want to become. Eventually the lines become a poem, story, essay, play, etc. In my experience, often when you sit down and think a line is going to grow into one kind of form, by the end, it’s in a completely different form. In that way, the writer is like a minor god. A flunky god who is trying to create, say, a panda, and ends up with a zebra. Or a platypus. Or gumdrop.

With that first book, the lines just wanted to become poems and what I like to call poelogues, and karaoke became the central metaphor for a kind of democratization of many things, including art and poetry, for better and worse, depending on which side of the mic you’re on, and who is singing, and who is trying to sleep.

LR: Do you work in different genres simultaneously? How do you switch gears between different genres?

EBL: Genres are for academics and book sellers, not for people who create things. Again, what’s most important to me is to have a poetic quality or poetic mode of consciousness to the thing, because that’s what feels most true to the experience of life for me.

LR: Was the process of writing your second manuscript different from writing your first and if so, how?

EBL: I guess a lot of poems in the first book were gazing backward. The second book is more attempting to look forward into the future. The title poem, “Whorled,” tries to contemplate a world of the future when all but a few of today’s world languages (and corresponding cultures) have gone extinct. Maybe it’s about making sure a part of me and the world I know (and remember) is still there? Because if the past can disappear, then so can the future. It’s not logical, of course. There’s this concept of “nostalgia for the future.” It’s from the writer Fernando Pessoa. I have memories of a Third World Korea, from childhood, shanty towns, how the people behaved, sounds and smells, long lost physical and facial gestures, etc. Korea is now basically a First World nation, though the suicide rate has gone from one of the lowest in the industrialized world in the 1980s to now the highest in the world. I feel very compelled to try to make an artful document of these shifts in consciousness.

And, after all, what is poetry if not also an effort to dismantle all temporal distinctions? The stereotype of time. Something like that.

LR: Whorled deals with the nuances and cultural specificities of language, simultaneously honoring and mourning its evolution and the inevitable loss that comes from that evolution. Can you talk a bit about the relationship between language and globalization in the book?

EBL: I’ve given stats elsewhere, but I think they’re worth repeating. Every two weeks the final living speaker of a world language passes away. Many linguists predict 90% of the world’s remaining 6,000 or so languages will become extinct by 2050. When a language goes extinct, so too do those speakers’ knowledge of cosmology, history, nature, health, psyche, myth, science, music, artistry, and ways of perceiving, thinking about, and assigning values within, the world. Language extinction (vs. language death, such as in the case of Latin and Sanskrit, which morphed into other languages and usages) equates to that particular culture’s total extinction. The same global and political engines that drive deforestation and loss of biodiversity drive linguistic and cultural extinction.

As someone who works with words, I’ve been ruminating over language extinction for over twenty years. It feels deeply personal. It’s the same feeling I would have if, say, the U.S. government issued a decree that the past tense was about to be systematically phased out of the English language.

And, in terms of my family, I’m aware that the Japanese attempted to obliterate the Korean language when they occupied Korea from 1910–1945. That colonial power, like many others, knew the power of language as the ultimate colonizer of a mind. My father was given a Japanese name in school, and forbidden to speak Korean. Poets and intellectuals were executed. He then later had to learn English when he emigrated to America, after the Americans and the Communists divided Korea into North and South. Somehow, though, through millennia, despite multiple and repeated colonizers, the Korean language remains grammatically in tact. Grammar is like the marrow of a language. Words, the lexicon, are more like the hair, with its changing styles. I like to think that this all says something about the people’s spirit, lurking like guerrilla rebels deep within the recesses of the grammar of this idiosyncratic language isolate.

In general, this tendency for colonial powers to deforest cultures and languages purely for profit, I find very disturbing. This Wal-Mart-ization of cultures. And yet, often the response is that maybe “weaker” cultures and languages should die out. Maybe the world would be better off with one single language to unite everyone.

On a poetic and artistic level, to (at best) contend that there’s nothing we can do about language extinction is like saying we should allow the ancient architecture in the world to be torn down and replaced with well-functioning strip malls because the crumbling Byzantine churches and Aztec pyramids have no real purpose any more, and will naturally fall into obscurity anyway. I disagree. What would human civilization mean without the Pyramids? Machu Picchu? It took eons to develop each culture’s language and grammar, and there is magic in every language. Each tongue is an organic, monumentally collective work of art, and every language possesses words for emotions and concepts that don’t quite exist in another language. What is duende in English? What is han (a Korean word for something like deeply regretful, resentful, passive, yet not hopeless sorrow) in English? I don’t think we always operate better with the mass marketing of an increasingly dominant and, as the linguistic tendency goes, an increasingly simplified grammar and language, all in the name of greater communication. Actually, I think it makes us dumber, which is terrible for communication.

The book tries to explore some of these sorts of spiritual legacies of colonialism and globalization, among other things. Confrontations. Celebrations, too. Ineffable evocations.

LR: Has your work as a translator informed your feelings toward language as you express them in Whorled, and if so, how?

EBL: I love language, from the inside out, outside in. Actually, I also think my favorite word might be the word “language.” As a kid, I always thought it sounded tasty, like sausage. But a really elegant, spiritually infused sausage.

I also love that there are so many creation myths. Humans come from a giant drop of milk. Humans come from a celestial being and a bear mating. Man comes from clay, woman from man’s rib. Etc. I want there to be as many creation myths and types of food and languages and butterflies and minerals and unique individuals and stories and poems, as possible.

A literal translation of any poem is always terrible.

LR: In both books, your poems attempt to grapple with the legacy of war – specifically the Korean War, which affected your family— and with the consequences of globalization. The narratives you create speak on the behalf of your own experience and that of your family, as well as encompassing a more universal perspective. How do you traverse the territory between the personal and the universal in your writing?

EBL: Get at the marrow.

LR: You have traveled very widely and have said on the subject of inspiration gathered from travel that “you have to get beyond the beauty (and horror, which is always there too) of any real place, and that’s hard to do unless something breaks the seal of your separation from it.” When you sit down to write about places where you have traveled, what do you do to allow that seal to break?

EBL: I guess I focus on the micro and macro breakages, in general, not the travels or places like a travel writer. But, yes, I do think if the seal gets broken while you’re in a new place, and you get impregnated with new, different stories or poison or antidote or history . . . new sub-atomic particles flow right into and co-mingle with your being through the breakage, large or small. Maybe this is why traumatic incidences enter us like blocks of ice. And a heartbreak in Paris will thankfully last a lifetime.

LR: Can you tell us about any new projects you have on the horizon?

EBL: A place-making project involving poetry and sculpture. We’re transforming an entire small town, Lanesboro, Minnesota, into a functioning artopia, a completely art-made place, every square inch, where people live and visit and engage with art on as many levels as humanly possible. During the economic downturn in 2008, the town (pop. 750) lost its only grocery store, and has continued to struggle . . . It’s a long story, so I guess I’ll just say: poems, in their many, many forms.

One thought on “A Conversation with Ed Bok Lee”