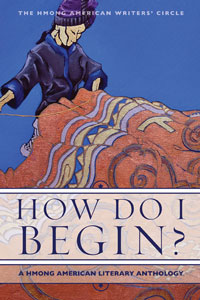

How Do I Begin? A Hmong American Literary Anthology | Heyday 2011 | $16.95

How Do I Begin? A Hmong American Literary Anthology | Heyday 2011 | $16.95

The NY Times began the new year with a piece about the Hmong American Writers’ Circle and the cultural context in which it operates. And our most recent issue of the Lantern Review put a spotlight on HAWC in Community Voices. This is only the beginning of much-deserved attention for this unique generation of new writers.

How Do I Begin is an apt title for an anthology of writers whose ethnic identity is doubly marginalized: though the Hmong roots are in southwest China, most emigrated/fled to the US from places like Laos or Vietnam after the Vietnam-American War. Burlee Vang, in his introduction to the book, describes himself as “born into a people whose written language has long been substituted by an oral tradition.” The written language of the Hmong was lost after assimilation in Imperial China long ago; this is not to mention assimilation into Thai and Lao culture, where most Hmong are provided an education only in their host countries’ official languages. The Hmong language has remnants in traditional embroidery but they have become indecipherable. Writers identifying as Hmong American today, therefore, have the tremendous task not only of writing themselves into history and literature, but also of gathering their names and identities from the pieces available. English is their adopted language, and so these writers must weave a warp and woof through multiple traditions.

The writing of themselves is a doubly difficult task because of the relationship between art and identity politics. Almost worth the purchase of the book alone are the short statements beginning each author’s pieces: in them, the writers describe their relationship to the term “Hmong American writer.” Many of How Do I Begin’s contributors wonder whether the Hmong part or the writer part takes primacy, and many are skeptical of the “object of exoticism” and of ethnic identity as “artistic limitation.” They struggle with negotiating the universal (empathy) and the individual (alienation). These writings are like a hand opening and closing, pulsing, from palm to fist. The impulse to “transcend ethnic and geographic boundaries” is paired with the impulse to preserve those boundaries and distinctions. Vang writes, “We have overcome ourselves. Our writing attests to this. Legitimizes us.” That overcoming is a matter of ownership and self-creation; yet the question of legitimacy is raised, and one wonders, On whose terms? Mai Der Vang uses the word paradox in her statement: “Writing for me has become a roadmap to navigate the paradoxes of life.” Sandra McPherson writes in her advance praise that these writers “are new to themselves and yet they already have their elders.”

Because their chosen language is English, these writers’ elders must be equated across cultures. The two epigraphs of Vang’s introduction, for instance, are from Shakespeare and Hmong American poet Pos L. Moua. The Shakespeare quote comes from Hamlet V.ii, when Hamlet describes waking suddenly on his execution-bound ship: “Sir, in my heart there was a kind of fighting, / That would not let me sleep . . .” He finds the letter from Claudius commanding England to behead him, and he rewrites the letter, thus rewriting his fate. The scene’s metaphor echoes with two of the last lines of verse in this anthology, from a poem by Mai Der Vang: “When all along you think the only war / is the one inside you.” And the epigraph from Pos L. Moua is the voice of a different elder: “Then they rode in canoes secretly arranged for them . . . / straight toward the world where the torches are burning.”

All throughout the anthology are reconfigurations of cultural inheritance. Iconic images like picket fences are challenged in Soul Choj Vang’s poem “Here I Am,” while the Carveresque image of fishing in Americais written from a different perspective in V. Chachoua Xiong-Gnandt’s “Lake Red Rock, Iowa” and then in Ying Thao’s essay “The Art of Fishing.” Martha Vang’s poem “Still Life of a Fruit Bowl” paints for us not apples and oranges but

plaintains, lychees, longans, and mangoes.

Pomegranate seeds are sprinkled around the

spiky jack and durian.

Soul Choj Vang’s “Our Field” lines up a mythic history of place names and people’s names that begins in the East and ends in the West. The poem concludes with the exhortation: “Hold on to our new fields!” Bryan Thao Worra’s “The Spirit Catches You, and You Get Body Slammed” plays with exotic expectations by taking us to Missoula with thoughts of “an auspicious moon above ancient Qin” while a shaman speaks enthusiastically in Hmongabout “Randy Macho Man Savage!” The image of the wrestling ring is an apt one as we think about the way these writers grapple with themselves in the box of their spaces, and as we think of Anthony Cody’s words, a Mexican American writer contributing to this anthology in the “hope to connect to tangents of the universal human experience and tie us to one another.”

The experience of the alien is another theme. That now-indecipherable embroidery, the paj ntaub, graces the cover of this book in an artistic rendering. In Burlee Vang’s author statement, he claims as his goal “some universal experience or truth, despite how alien the world, situation, or characters . . .” Andre Yang’s poem “Cousins” gestures at a painful language of love and recognition even “amongst the chorus of insects / that must have been so familiar to you, that were so foreign to me.” Bryan Thao Worra’s poem “Modern Life” ends with the speaker

Waiting for the cops in their fancy cruisers

To blink

So our race can begin

That is a blink of longed-for recognition from authorities, and it is a blink that quickens the gap between the alien and the invisible.

There is a self-estrangement involved in all writing, in the creation of all memories, and it is useful to consider Ka Vang’s formulation: “Being Hmong makes me a better writer and being a writer makes me a better Hmong.” This awareness of a split identity is one of upward lift, like two waves rising in their collision.

I cannot stress enough the importance of this anthology, or how exciting it is to read these new voices and see the stirring of a people in words. I believe that the work of this anthology is not merely one of extending history or of grafting on labels. “Hmong American literature” is not a name; it is a conversation, an evolution. Bryan Thao Worra writes:

There is often the implication that ethnicity can be separated or masked in writing. This cannot be done any more than we can disguise the time in which we write. [. . .] my work remains, and that is my true body.

One thought on “Review: How Do I Begin?”