A Guest Post by Stephen Hong Sohn, Assistant Professor of English at Stanford University

In thinking about the so-called state of contemporary Asian American poetry, I am most struck by the issue of the proliferation of small presses that have remained afloat through print-on-demand publication policies and through the strategic limited print-run system. American poets of Asian descent have certainly been a beneficiary of this shift as evidenced by hundreds of poetry books that have been published within the last decade. In 2008 alone, there were approximately 20 books of poetry written by Asian Americans, the majority of which were published by independent and university presses. Of course, on the academic end, the vast majority of Asian American cultural critiques, especially book-length studies, have focused on narrative forms, but the last five years has seen a concerted emergence in monographs devoted (in part) to Asian American poetry, including but not limited to Xiaojing Zhou’s The Ethics and Poetics of Alterity in Asian American Poetry (2006), Interventions into Modernist Cultures (2007) by Amie Elizabeth Parry, Race and the Avant-Garde by Timothy Yu (2008), and Apparations of of Asia by Josephine Nock-Hee Park (2008). As a way to gesture toward and perhaps push more to consider the vast array of Asian American poetic offerings in light of this critical shift, I will be highlighting some relevant independent presses in some guest blog posts. I have typically worked to include small press and university press offerings in my courses, having taught, for example, a range of works that include Sun Yun Shin’s Skirt Full of Black (Coffee House Press), Eric Gamalinda’s Amigo Warfare (WordTech Communications), Myung Mi Kim’s Commons (University of California Press), Timothy Liu’s For Dust Thou Art (Southern Illinois University Press).

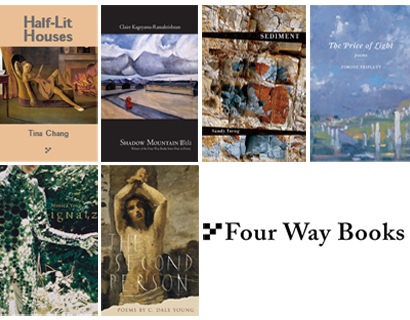

In this post, though, I will briefly list and consider the poetry collections by American writers of Asian descent that have been put out by Four Way Books (New York City), headed by founding editor and director, Martha Rhodes—and will spend a little bit more time discussing Tina Chang’s Half-Lit Houses (2004) and Sandy Tseng’s Sediment (2009). Currently, Four Way Books’ list is comprised of:

Tina Chang’s Half-Lit Houses (2004)

Pimone Triplett’s The Price of Light (2005)

C. Dale Young’s Second Person: Poems (2007)

Claire Kageyama-Ramakrishnan’s Shadow Mountain (2008)

Sandy Tseng’s Sediment (2009).

Were I to constellate the commonalities between these five collections, it would be clear that the editors at Four Way Books are very committed to the lyric approach to poetry, in which the connection between the “writer” and the lyric speaker seems more unified. I have taught Pimone Triplett’s The Price of Light in the past, specifically for my introduction to Asian American literature course. What I find most productive about this collection is its very focused attention on “lyrical issues” of the mixed-race subject. In The Price of Light, one necessarily observes how distance from an ethnic identity obscures any simple claim to authenticity and nativity. In The Price of Light, a lyric speaker returns to one vexing question: what does it mean to be Thai? To answer this question, the reader is led through a unique odyssey, where issues of poetic form, tourism, and travel all coalesce into a rich lyric tapestry.

C. Dale Young’s The Second Person: Poems continues the exciting poetic trajectory envisioned in his first collection, The Day Underneath the Day. I am especially energized by Young’s texturizing of the lyric landscape through the consideration of Caribbean geographies, ones that complicate the notion of the “American” in Asian American literature. Further, the inclusion of medical vocabulary, no doubt influenced by Young’s work as a physician, uniquely stylizes his poetry, offering a heterogenenous semantic terrain that is breathtaking and wide-ranging.

Claire Kageyama-Ramakrishnan’s stunning debut, Shadow Mountain, reminds me of the importance of the “latency” affect that has structured the appearance of Japanese American literatures concerning the internment experience. It is not unlike Lee Ann Roripaugh’s Beyond Heart Mountain in this regard, and the lyrical excavation important in contouring how the internment continues to reach across generations.

I’d also like to consider some specific poems from Chang’s Half-lit Houses and Tseng’s Sediment. One of my favorite poems from Half-Lit Houses appears early on in the book; I reprint an excerpt here:

Invention

On an island, an open road

where an animal has been crushed

by something larger than itself.It is mangled by four o’clock light, soul

sour-sweet, intestines flattened and raked

by the sun, eyes still savage.This landscape of Taiwan looks like a body

black and blue. On its coastline mussels have cracked

their faces on rocks, clouds collapseonto tiny houses, and just now a monsoon has begun.

It reminds me of a story my father told me:

He once made the earth not in seven daysbut in one. His steely joints wielded lava and water

and mercy in great ionic perfection.

He began the world, hammering the lengthof trees, trees like a war of families,

trees which fumbled for grand gesture.

The world began in an explosion of fever and rain.He said, Tina, your body came out floating.

I was born in the middle of monsoon season,

palm trees tearing the tin roofs.Now as I wander to the center of the island

no one will speak to me. My dialect left somewhere

in his pocket, in a nursery book (6).

This poem is largely instructive in the way that Chang continually subverts the nostalgic reclamation of family history and ethnic attachments. The opening moves us into this framework with the graphic depiction of roadkill as a metaphor for the way that Taiwan itself might appear geographically, but we also know that this connection links itself back to the lyric speaker’s heritage. The “Tina” of “Invention” is not born in the welcoming embrace of perfect weather, but in that of “monsoon season.” It is no surprise then that her journey to Taiwan is itself replete with a sense of isolation, as “no one will speak to” her. Tina’s father is posited as a laborer, but this force is one likened to “trees like a war of families,” and we begin to see the conflicts that will emerge throughout the rest of the collection. For instance, in “Famine,” the readers are treated to a historically distant poem that situates the difficult conditions that structure the family lineage of the lyric speaker:

Famine

[Hunan, 1932]Mother explains her love of heat

as she stirs over a burned pan.We collect them one by one:

beetle, ant, june bug, roach, gnat, firefly.The cow crumbles on its thin legs.

And the dust over a million eyes.We let go of a handful. Tiny black legs

spinning on a mound of sugar.Let us eat, thankful for the small things

that wander by the window or a door.We grasp what flits by us, flashing (35).

In this case, we recall the very difficult situation that reconstructs insects—not as some quaint local color—but as objects for consumption. The lines here are indicative of Chang’s spare and direct lyrical style, which works at its best when disorienting the reader’s expectations. I end my brief discussion of Chang’s Half-lit Houses with the intertextual lyric “shout-out” in “Stain,” where Agha Shahid Ali’s presence is made known. I always find these moments fascinating because they point to a multiply inflected poetic teleology, where the influences of romantic poetry or American free verse must stand alongside Asian American poetry as its own specific subarea. In “Stain,” reprinted below, the lyric speaker finds inspiration in an empathic connection to Ali’s poetry:

I read of Ali’s Kashmir, his country falling

beneath an elephant’s foot, the heaviness

that breaks the dry ground and the high cry

of an impending siren. I want to tell everyone

of my alarm. That I am afraid for them.

We must all admit what we fear in the lush

hazard of the waking heart, for what it wants

is to rest, a red flag hidden in uncertain

camouflage, to disappear inside a stupor fog (79).

Sandy Tseng’s Sediment is peculiar for the elliptical nature of its various poems. Structurally, the first section mostly coheres around a themes of alienation and descent similar to the ones found in Chang’s Half-lit Houses. As in Half-lit Houses, ethnicity never provides a direct mapping of identity and history:

Somewhere along the line,

a native entered the family

on my father’s side and left

his dark skin on us.There are some things I’ve never asked

and always wanted to know.

The sound of rain tapping on tin

no longer soothes me to sleep.

We begin to adapt to our surroundingsbut cannot give in completely.

It’s a task of finding

the right hole for the square peg

and not being able to fit it

perfectly into anything.I imagine that my skin is not the color of fire.

When I am born, no one will fly me

across the ocean to raise me

in another country. I imagine that

I am a round peg in a round hole.The breath is being pushed out of my lungs

by the hands of something

unknown, the palms

pale as the sidewalks.

I imagine so many things (5).

Once again, the question of belonging surfaces through the oft-used metaphor, “the right hole for the square peg/ and not being able to fit it/ perfectly into anything” (5). We are immediately led to think about the topic of miscegenation, as the opening lines tell us, “Somewhere along the line,/ a native entered the family/ on my father’s side and left/ his dark skin on us” (5), directing us again to descent and lineage. Where does the lyric speaker belong? Such questions continue to galvanize the poems’ openings. Such is also the case with “From the First Generation.”

From the First Generation

The name I gave myself was altered by my parents’ accent.

The neighbors showed us how to spell it on a yellow notepad.Our first Thanksgiving we cringed at the stuffed bird open and gaping

on the table.We drank large glasses of milk everyday. Our bones grew slender

and long, the height of a people increasing as our feet touched the land.I have heard my mother come home late in the evening. Some days

I could not wear the $40 sweater I begged her to buy.There was a boy whose family hid in caves during the war, a man who

can still taste the C-rations he ate with a soldier.We can never go back. I’ve wanted to pack everything into a box, ship it

back overseas with a note explaining (9).

Here, the problematic of assimilation looms ominous over the immigrant family, where the child’s naming does not proceed seamlessly, and instead is “altered by” accent. Perhaps, most salient to the recent holiday, Thanksgiving emerges as a day that constructs the immigrant family as other, where the object of consumption is “gaping,” rather than inviting. Food therefore structures one way into the fabric of immigrant identity, where belonging might be accessed through ingesting appropriate dishes or drinks, but where one’s past cannot be escaped, as evidenced by the “man who/ can still taste the C-rations he ate with a soldier,” an ever present reminder that what one eats cannot be divorced from such complex culinary archaeologies.

In one of the most precise and crystalline poems from “Sediment,” Tseng’s “The Merchants Have Said It” recalls Chang’s “Invention” in exploring the way that a subject might find himself foreign to the very landscape with which he might claim an ethnic affiliation:

The Merchants Have Said It

In the courtyard, laundry dries in the aroma of fried fish

with a bit of garlic from someone’s fingers. I hear

the voices from the alley. The merchants have said it.

I am too tall. Because somewhere I drank milk as a child.

And somewhere my face was not weathered

by Mongolian dust blowing from the north. I hear the whispers

through the bed sheet curtains. The way I hold my head

gives me away. Although I cut my hair and buy clothes off the street,

still I walk like a foreigner. My stride is too long, too quick.

But if I hide my fingernails and slouch, if I look no one in the eye,

someone will take the offered coins without a word (18).

There is the sense of the authentic local atmosphere, replete with the “aroma of dried fish” and the “voice from the alley.” Even given her enterprising journey through this terrain, the lyric speaker has perhaps intruded, as she is still “like a foreigner.” Interestingly, the poem ends on a note of shame, as the lyric speaker will not “look” anyone “in the eye,” so that any transactions might occur without challenging inquiries or the broaching of difficult topics.

In providing just a brief view into Four Way Books, my aim has simply been to highlight the exciting and innovative work being produced out of independent presses. Of course, Four Way’s commitment to its poets continues, as Martha Rhodes has already contracted the future collections of C. Dale Young (Torn in 2011) and Monica Youn (Ignatz, April 2010), as well as the forthcoming collections of Tina Chang and Claire Kageyama-Ramakrishnan.

* * *

Stephen H. Sohn is an Assistant Professor of English at Stanford University.

To find out more about Four Way Books, please visit their web site at www.fourwaybooks.com.

Lovely guest post. Thank you.