This week’s prompt is about using features of the visual world as a way to write across historical moments, geographic space, and time. This is a technique I’ve been using a lot in my recent work, and when putting the finishing touches on a fellowship application essay this week, I found myself articulating for the first time why this approach is such a powerful one.

At times, making poetry becomes a kind of transcendent experience. Tracing certain images through time shows the way in which all experience is radically unified—by screens, wires, flashes of light, images of transubstantiation, to name just a few.

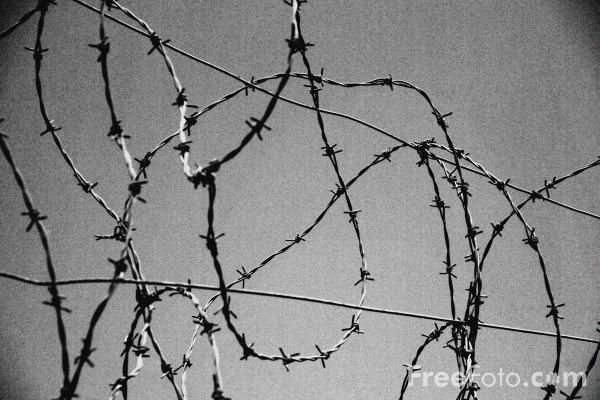

Thus the child sweating at night, afraid for her parents’ safety at the hands of a Communist government, is not as alone as she once thought. She clenches her sheets, dreams of centipedes whose scaly bodies become an endless braid, and yet the pattern of her nighttime torment finds an uncanny double in the long stretch of wire wound and barbed around her grandparents in a 1945 American internment camp.

Different time and place, same image. Same condition. To me, this thinking represents a kind of radical, redemptive vision, one that suggests experience is not so fractured as we believe it to be. By undoing logics of nation, political geography, and even chronology, it offers us an imaginative vision that is wholly other, wholly whole.

Your poem doesn’t need to trace as emotionally loaded an image as barbed wire or braided centipedes — the example I’ve chosen is an extreme one, used to illustrate the point that the visual qualities of our surroundings can actually echo past moments, other places, different realms of experience. Tracing these features can reveal unexpected linkages between unexpected circumstances.

In some ways, this isn’t that different from using a person’s name, or a particular scent, as a way to shift the narrative frame of a poem from one setting to another. It’s just that here, the “catalyst” is visual.

* * *

Prompt: Write a poem that “shifts” in some way — through time, across space, between points of view, to show the unexpected relationship between separate worlds of experience. Use a visual cue, object, or feature of the speaker’s surroundings to recall them to a different “place,” however you choose to interpret it. If you like where the poem is going, let that same image lead to multiple shifts. Pay attention to other visual features in the “worlds” you explore as well, but keep in mind that not all images are as rich with potential as some.

Post your ideas, attempts, or even just a short list of “visual cues” you think other readers/writers could use in tracing their poetry across experience.