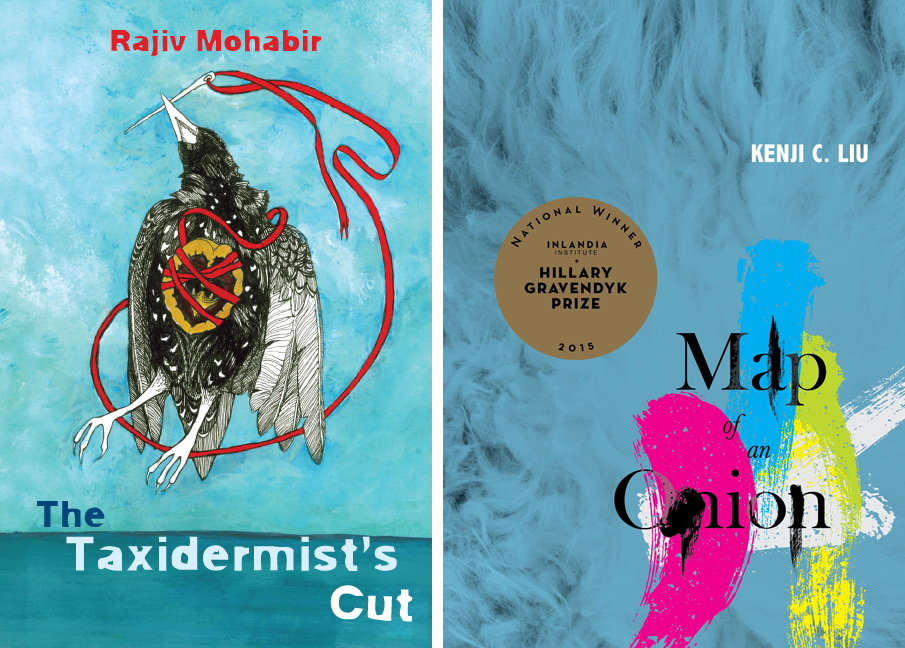

This month, our Summer Reads include Rajiv Mohabir’s The Taxidermist’s Cut (Four Way Books, 2016) and Kenji C. Liu’s Map of an Onion (Inlandia Books, 2016), two remarkable debut collections that feel so fully conceived, so urgently and articulately expressed, that one hesitates to call them “debuts,” as these are clearly two poets who have been at this for longer than the term “first book” implies. Deeply theorized, expertly crafted, and placed squarely in conversation with the poets’ respective family histories, cultures, and discourses of science and post-colonialism, these works draw the reader into a thoroughgoing investigation of what it means to be human, delivered into a specific time, body, and cultural milieu. These poems are the maps they have fashioned for themselves, forging a poetics of reckoning in pursuit of generational and lived truth.

In The Taxidermist’s Cut, Rajiv Mohabir’s lines, both sinister and lovely, function as cuts that reveal and divide, shimmering with the erotics of violence. Transfixed, one finds oneself unable to look away, arrested by the elegance of the language and the way, when held to the skin, it causes the body to shiver with pleasure. The line, the body, the text, the means by which bodies make and destroy themselves; “Pick up the razor. // It sounds like erasure.” Formally, the couplet features prominently throughout, raising the question of what’s joined, what’s split, what adheres together and what pulls apart. Stitched through with found text from Practical Taxidermy, The Complete Tracker, and other taxidermy-related manuals, the poems confront the body with a mixture of scientific detachment and intimacy, as the life of the body—its homoerotic desire, its violation—is rendered in acute detail. Members of Mohabir’s family, past and present, drift in and out of The Taxidermist’s Cut, as, marked by a pilgrim poetics of wandering, the book moves through the West Indies, the South, boroughs of New York City, reckoning with memory, desire, and histories of conquest and slavery. These poems are breath caught from the throat, blood cut from a wound—the cry that follows, in pleasure, in pain, indistinguishable from song.

Kenji C. Liu’s Map of an Onion, a work deeply textured by memory and place, maps its own set of explorations beyond and within cartographies of language, national borders, and the body. Like Mohabir’s, Liu’s subjectivity is shaped by multiple histories and homelands, all impressed upon a poet who writes with deep sensitivity to the pre-colonial realities of place, drawing us into greater awareness of what it means to be American, immigrants, humans. “Ghost maps are hungry maps,” he writes, tracing lineages and interlocking histories through time. It’s a mapmaking of the self, a “search translated between my family’s four languages.” Marked in places by profound longing (“Home is on no map, and explorers / will never find it. That time has passed”) the poems, in their searching, take us from Mars to Moscow, suburban New Jersey to the World War II Philippine jungle. The book itself, neatly sized and beautifully produced, fits compactly in the reader’s hand and brings to the body an awareness of itself as a artifact translated across cultures, yet possessing a language all its own. Map of an Onion, too, concerns itself with the act of incision, especially of paper, “the surgery of documents” cutting ruthlessly across land, sea, and families. What binds and what breaks—folded, torn. “Taste your own / luscious // fissures,” the poet says, the places where selves meet; the sinew, cartilage, and tendon of bodies that are bound and, simultaneously, transcendent.

* * *

What books are on your summer reading list? We’d love to hear about them! Leave us a comment below or share your best recommendations with us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram (@LanternReview).