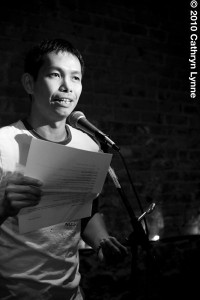

Jee Leong Koh is the author of three books of poems, including the recently published Seven Studies for a Self Portrait (Bench Press). His poetry has appeared in Best New Poets (University of Virginia Press) and Best Gay Poetry (A Midsummer’s Night Press), and in journals such as Cimarron Review and PN Review. Born and raised in Singapore, he lives in New York City, and blogs at Song of a Reformed Headhunter.

* * *

LR: Seven Studies for a Self Portrait is divided into seven chapters, with seven poems in each chapter, and forty-nine in the last. What is the significance of the number seven?

JLK: Seven days in a week. The practice of writing a poem a day is important to me. The days when I don’t write feel empty to me, incoherent, lost. A day, like a poem, is invaluable for itself and also for being a part of something larger, like a week or a life. I wrote my first book Payday Loans, a series of 30 sonnets, in the month before I graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with my MFA.

One of my favorite poets, Philip Larkin, asks in a poem, “What are days for?” He answers himself, as poets have the habit of doing, “Days are where we live.” A day is an on-going project. At the moment I am reading Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. She speaks of Nietzsche’s will to power as a project of self-transcendence. When Larkin considers transcendence, he says in his typically sardonic manner that the question brings the priest and the doctor running. Because I have lost my faith in organized religion and have yet to place my life in the hands of medical science, I am working out my daily transcendence in writing poetry.

I wrote Seven Studies for a Self Portrait in two years. As I wrote, the number seven acquired and transformed its Christian meanings—the days of Creation, the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Eshuneutics, who reviewed my book, puts it well, “This silent structuring … evokes a tradition running from the mediaeval period and sets a context for the spiritual enquiries within the book.” Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, from which my book got its epigraph, was an inspiration for the post-Christian enquiry.

As vital as the spiritual quest was for me, so was the musical composition that the number enabled. A sequence of seven poems has not only a beginning and an end, but also a well-defined middle. It also breaks up into two unequal parts—four and three—half of the sonnet’s proportions. The first six sequences in fact culminate in two sonnet sequences, one English, the other Italian. Breaking through and re-working that framework is the final set of 49 ghazals, each made up of seven couplets about love. The ghazals raise, in my imagination, a 7 x 7 x 7 cube. In planning this structure, I was thinking very much of Herman Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game, in particular, the last game that the Magister Ludi builds from the floor plan of a Japanese house.