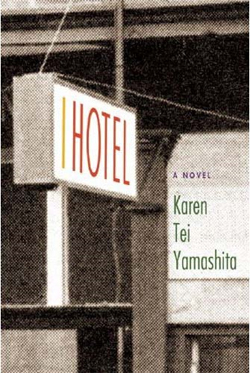

Karen Tei Yamashita—writer, professor, and globetrotter—possesses an oeuvre that is anything but conventional. From her debut eco-fantasy novel Through the Arc of the Rainforest to her latest novel, the incredibly ambitious I Hotel, Yamashita has time and again demonstrated a preoccupation with offbeat human experiences.

At the center of I Hotel is the history of the titular inn, the International Hotel, a low-income housing complex located in San Francisco that became the source of much controversy and conflict when its residents, mostly elderly Filipino and Chinese bachelors, were threatened with eviction in the 70’s. Working with this historic centerpiece, Yamashita crafts a highly experimental novel comprised of prose, screenplay, quotes, analects, and even comics. And in an effort to give it a more comprehensible structure, the novel is divided into ten “novellas,” each corresponding to a year between 1968-1977. For research, Yamashita interviewed residents from the community, and their stories serve as seeds for the novel. Despite her efforts to shape the novel around fictionalized versions of these culled stories, the “fiction” elements end up coming across as secondary to the overwhelming amount of synopsized history and culture that fills the novel in the form of primary source-like documents. Thus, we have a “novel” in which the most compelling sections are the ones that feel least like a novel.

In each novella, we’re afforded glimpses into the lives of various protagonists. In an interview with Kandice Chuh for Discover Nikkei, Yamashita said she roughly structured the book so that each “novella” followed three central characters, with one typically serving the role of a mentor. Characters include the son of activists, a saxophonist, and a dancer, among others. But despite being modeled on actual people these colorful figures feel hastily formed, like participants in a dress rehearsal. The scenes they exist in feel ethereal and unanchored. There’s no sense of settling into moments and scenes and exploring characters and their connection to their settings. Instead, there is mostly dialogue, and not even very effective dialogue. The dialogue often is too heavy-handed or too inconsequential. Despite efforts to spotlight characters and how they negotiate trying circumstances, what takes precedence is an overriding narrative voice that attempts to bridge them all together.

More often than not, what hamstrings the conventional narrative threads is the intrusion of an overriding polemical voice that waxes and wanes about humanistic subjects such as philosophy, history, politics, film, art, and literature. The personal stories are undermined in part because when the novel does digress into the polemical mode, the most compelling writing actually arises. In several of these sections, the language is mesmerizing. There are passages that are so stylistically crisp and stirring that I initially reread them to deconstruct the source of their power:

“Do you command great armies and oversee great territories, or are you the fodder of stinking bodies sacrificed at the front? Do you rule by the will of God or the Mandate of Heaven, or do you grovel in the dirt for your subsistence and share your food with animals? Do you stand at the pinnacle of power, however precariously protecting, with the great umbrella of your powerful arms and silken sleeves, a hierarchy of hapless fools and ungrateful subjects, or are you a struggling peon of unfortunate birth? …The rise and fall of civilizations held in dusty monuments for thousands of years may suddenly be compressed in no doubt brilliant minds to explain the present moment.”

Yamashita is fluent in the language of so many disciplines and subcultures that no matter the subject being explored—whether it’s French poets, Marxist theory, or Imelda Marcos—the writing feels commanding.

The fluency and command Yamashita demonstrates, however, cannot mask the novel’s lack of narrative cohesion nor can it salvage characters that seem never to set themselves apart from the farrago of activity all around them.

But I suspect this lack of cohesion is due less to oversight and more to the progressive aspirations of the text. The novel (if it can even be called a novel) is so brimming with experimentation and historical substance that it ignores more traditional narrative preoccupations, like continuity, character development, and standard conflict resolution structure. But this doesn’t make it an inferior work; it just makes it different, in my opinion. That’s not to say the novel isn’t without it’s shortcomings, but with a certain mindset the shortcomings can be seen as consequences of a different kind of preoccupation, one geared less to achieving the typical objectives of a novel and more towards rendering a kind of spoken word historical epic that captures the zeitgeist of one of the most transformative periods in American history.

While reading I Hotel, I couldn’t help but call to mind Junot Diaz’s critically acclaimed novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Specifically, I thought of a statement Diaz made in an interview, in which he said he initally planned for Oscar Wao to be a multimedia extravaganza filled with comics, web site tie-ins, and other postmodern pyrotechnics. In the end, though, Diaz reigned in his ambitions in favor of a more formally conventional family saga that was distinguished by its unconventional voice. In I Hotel, Karen Tei Yamashita seemingly aims to realize the mega-project Diaz abandoned by creating a novel that combines various formats and syncretizes diverse voices in order to capture the complexities of a community caught up in the turbulent currents of history’s unfolding.

Whether she has created something compelling and worthwhile depends on your expectations going into the book; if you’re expecting clearly rendered stories that will resonate and stick with you, then I Hotel may not be for you, but if you’re looking for a head rush from reading about a host of interesting subjects in a variety of unconventional formats, then you’re probably in the right place.