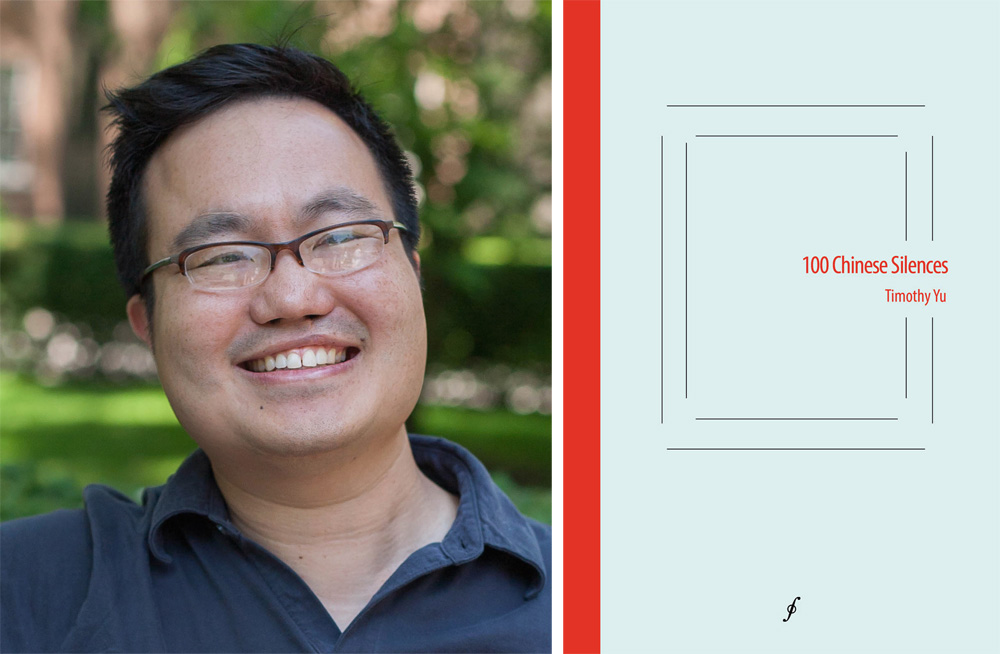

In honor of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, we interviewed leading scholar and poet Timothy Yu, author of 100 Chinese Silences (Les Figues Press, 2015), Race and the Avant-Garde: Experimental and Asian American Poetry Since 1965 (Stanford, 2009), and the three chapbooks 15 Chinese Silences (Tinfish Press, 2012), Journey to the West (Barrow Street, 2006), and Kiss the Stranger (Corollary Press, 2012). Yu is professor of English and Asian American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and he spoke with us, among other things, about the need for greater historical contextualization of Asian American poetry, the process of writing 100 Chinese Silences, and the vibrant relationship between his creative and scholarly work.

* * *

LANTERN REVIEW: Within the literary and academic world, you function in a variety of roles. What’s it like to wear so many different hats? We’re especially curious about the ways in which these roles (poet, cultural critic, scholar, teacher, editor, etc.) overlap, or if there are times when you find them in tension with one another.

TIMOTHY YU: I’ve always written poetry, but for a long time my identity as a poet was peripheral to my professional identity as a scholar. I did a PhD in literature, not an MFA, and until pretty recently I never really published much of my poetry. There’s a lot I could say about this, but I think that it was my scholarly training, and in particular my study of Asian American poetry, that gave me a greater sense of confidence in my work, and ultimately a clearer sense of what I wanted my poetry to do.

But it was definitely a struggle along the way sometimes. In grad school, although quite a few of my classmates were also creative writers, there was an old-school sense among faculty that being a creative writer was not compatible with the “serious” identity of scholar. I kept my poetry going largely by finding a community outside of the university—I went to readings, joined a writing group, sometimes took creative writing workshops elsewhere during the summers.

It’s really only in the past few years that my roles as poet and scholar/critic have begun to converge. A lot of that has to do with my finding a community of other Asian American poets through Kundiman. Although I had studied Asian American poetry for some years, I don’t think I began to see myself as an Asian American poet until I became a Kundiman fellow and saw what being part of an Asian American literary community could mean. I think this understanding has allowed my scholarly work increasingly to feed my creative work, which is basically what led to 100 Chinese Silences.

Now I think I’m experiencing this wonderful feedback loop where my creative work is also pushing my criticism to new places. Probably the best example of this was in the controversy around Calvin Trillin’s poem in the New Yorker, “Have They Run Out of Provinces Yet?” My response was both creative and critical: I wrote a parody of Trillin’s poem that was published on Angry Asian Man, which led to me getting interviewed on NPR, which was followed by my being asked to write an essay for the New Republic. And in that piece, I tried to combine my scholarly knowledge with the emotion I was feeling as a member of the Asian American poetry community—which I think made all the difference to its success.

LR: You’re the author of the chapbook 15 Chinese Silences, which was published in 2012. Four years and eighty-five Chinese silences later, the book-length 100 Chinese Silences is in print. Can you tell us a bit about how this project evolved? How did it find its trajectory?

TY: The Chinese Silences began when Billy Collins came to Madison to do a reading. There were something like 1,200 people there! Anyway, Collins read a poem called “Grave,” in which he is standing at the graves of his parents, and he says that his father’s silence was like “the one hundred different kinds of silence according to the Chinese belief.” Now, I’m not an expert on all things Chinese, but that didn’t sound familiar to me. And then at the end of the poem, Collins admits that the idea of 100 Chinese silences was something he had “just made up.” In my annoyance, I immediately vowed that I would write these 100 Chinese silences, although at the time I didn’t know what I meant by that.

I started off by simply writing a parody of “Grave,” one that tried to turn the idea of “Chinese silence” on its head. I quickly discovered that Collins had, in fact, written a lot of poems about China (or Asia), and so I continued by parodying those poems. Collins provided me with more than enough material for the first fifteen poems in the series, which became the Tinfish chapbook 15 Chinese Silences.

I soon realized that the project, which had started off as a bit of a lark, was leading me into deeper waters, and that to explore them, I was going to need to move beyond Collins toward a broader investigation of how China and Asia are portrayed in contemporary American poetry and culture. It turned out that there were many more poems than I expected, by a wide range of poets; some I just found by doing things like searching the Poetry magazine archives for “China.” The poems I found ranged from elegant invocations of Chinese poetry to cringingly offensive uses of stereotype and pidgin. After a certain point, people actually started sending me examples—“here’s a good one for you!”—and so I pretty much had an inexhaustible supply of material.

Of course, the tradition of poetic orientalism I’m exploring isn’t just a contemporary phenomenon; it goes at least back to the dawn of the 20th century and modernism, so at a certain point, I had to begin delving back into that earlier tradition. I did this a bit tentatively at first, starting with a parody of Gary Snyder’s “Axe Handles” (No. 38) and eventually reaching back to modernism: Marianne Moore, W.B. Yeats, and, of course, Ezra Pound, whose poetry is the subject of the final dozen or so poems.

So, the sequence unfolds pretty much in the order it was written, but that order does represent a fairly conscious movement from contemporary poems about Chinese stuff back to the modernist roots of American poetic orientalism.

LR: Given the book’s wide variety of source material, how did your creative process differ with poems responding to, say, Collins and Tony Hoagland (living, contemporary poets), as opposed to Marianne Moore and Pound (deceased, “canonical” voices)? Or did it? What about your responses to more journalistic sources, such as the speech by Newt Gingrich or David Sedaris’s piece on China?

TY: Rewriting Moore and Pound was certainly more intimidating than rewriting Collins or Hoagland! For the more contemporary writers, my tone sometimes bordered on the snarky. But of course, there was some element of reverence in my approach to figures like Moore and Pound, even as I was trying to mount a critique of their work. It’s probably why I put off grappling with them until much later in the series, when I felt I had more confidence in what I was doing.

Responding to some of the journalistic sources was actually fun, because those were the places in the series where I had a bit more freedom. Much of the series was written under fairly strong constraint; I strove to mirror the style and even the line structure of the originals. But with something like the response to Sedaris, I was able to play around more freely with the grotesque imagery of disgust Sedaris uses in his description of China. The most fun piece in this regard was No. 26, which collaged reporting on Wendi Deng (the then-wife of Rupert Murdoch, who made headlines by slapping down a protester who tried to hit Murdoch with a pie) to the tune of Blake’s “The Tyger.”

LR: How have audiences responded to 100 Chinese Silences?

TY: People seem to like and respond to these poems more than anything I’ve ever written—which of course I have mixed feelings about, since nearly all of them are rewritings of other poets’ work! But I think that is part of the project—trying to use the pleasure and humor of these parodies as a Trojan horse for a certain kind of critique.

I’ve been very gratified by the way that Asian American readers, in particular, have responded to the work—they’ve really embraced it warmly as a way of talking back to a certain tradition, which has been so important to my being able to complete it. I’ve heard a little skepticism from some readers about the way I take on certain poets, Pound in particular, who are not as easy targets as, say, Collins. I certainly think that the poems where I’m rewriting canonical writers are the riskiest and the most open to ambivalent interpretation.

LR: As a literary journal dedicated to the promotion and publication of Asian American poetry, Lantern Review has thought quite a bit about what it means to be an advocate for change in today’s literary climate. In your opinion, what is the most pressing cultural work that needs to be done right now?

TY: I think there is a growing awareness that the voices of people of color need to be heard, and indeed, need to be front and center, in contemporary culture, but there is also awareness of how far we are from having the kind of cultural discourse where that is the case. I think it’s absolutely vital for Asian American writers and other writers of color to continue to build their own spaces—whether that’s publications like Lantern Review or organizations like Kundiman—while also demanding more mainstream representation; the two are not mutually exclusive but go hand in hand. I also think it’s crucial for us to provide a greater sense of the history of racial discourse; the conversations and conflicts we’re having today are not new, but emerge from long histories and deep contexts. This is where I think scholars/critics and poets absolutely must be talking to and learning from each other. Simply having a sense that there is an Asian American literary tradition is an incredible boon to a young Asian American writer.

LR: What are some of the most exciting things happening in Asian American poetry today? What are you currently reading?

TY: The breadth and depth of what’s happening in Asian American poetry is just astonishing. To me, Asian American poetry is a space where the lyrical, the experimental, the performative, the political—things too often separated in the larger poetry world—can engage and infuse each other. Just looking at my nightstand, I see amazing new and recent books by Sueyeun Juliette Lee, Brandon Shimoda, Khaty Xiong, Nicholas Wong; books by international Asian writers like Sarah Howe and Fred Wah. And the wider world is taking notice.

LR: After 100 Chinese Silences, what’s next? Can you tell us about any new projects currently underway?

TY: I’m working on a new sequence called Chinese Dreams, and yes, it’s another rewriting—this time of John Berryman’s Dream Songs. I’m fascinated and deeply troubled by Berryman’s framing of his anguished personal lyrics through racially stereotyped language, and I’ve been trying to see what I can do with that from an Asian American perspective.

* * *

Timothy Yu is the author of 100 Chinese Silences, the editor’s selection in the Les Figues Press NOS Book Contest, and of Race and the Avant-Garde: Experimental and Asian American Poetry Since 1965 (Stanford), winner of the Book Award in Literary Studies from the Association for Asian American Studies. He is also the author of three chapbooks: 15 Chinese Silences (Tinfish), Journey to the West (Barrow Street; winner of the Vincent Chin Chapbook Prize from Kundiman), and, with Kristy Odelius, Kiss the Stranger (Corollary), and the editor of Nests and Strangers: On Asian American Women Poets (Kelsey Street). He is professor of English and Asian American studies and director of the Asian American Studies Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.