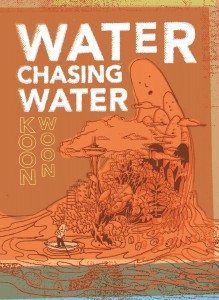

Water Chasing Water by Koon Woon | Kaya Press 2013 | $14.95

In Koon Woon’s Water Chasing Water, a river appears in one poem and flows into the next, appearing there as rain, turning up in one place as an ocean and in yet another as a damp and soggy sadness. I was immediately reminded of lê thi diem thúy’s The Gangster We Are All Looking For, and there on thúy’s first page: “Ba and I were connected to the four uncles, not by blood but by water” (3).

Woon’s text gestures toward the meanings of water—as life-giving force, as connective tissue, as that which carries us. lê thi diem thúy explains that “In Vietnamese, the word for water and the word for a nation, a country, and a homeland are one and the same: nu’ó’c.” In Thai, the word for river (แม่น้ำ) is made up of the word for mother (แม่) and the word for water (น้ำ). For the diasporic fish/ghost/dish-washer in Woon’s poems, water connects places to other places, traveling from person to person and washing up memories and other debris.

As if glazed in the afternoon heat,

the blackberry brambles are still and

quiet, the steel rail expanding,

and once the roar of a rumbling freight

passes and dies, the slough,

quiet again with its currents,

becomes water moving on

in my unregulated childhood.[. . .]

In the waters between us are

the gurgling sounds of childhood empires

and paper boats, and in the parcels of land

that sustain us, the memories of stickers

and hand-staining berries;

in nights of sleep,

a child’s reworking of paradise. (“As If,” 5)

In the poem “Coastal Highway 101, 1960,” Woon remembers U.S. 101, the highway that runs down the western edge of California, Oregon and Washington, as a river. A rhythm develops with the repetition of the lines “It was in effect a river of sorts—”, “It was in effect a town of sorts—”, It was in effect a time of sorts—” and “It was in effect a life of sorts—” (7) as the highway moves through historical references and geographical landmarks, evoking lines of commerce and economies of travel.

The highway, like a river, expands to fill the distance, like water poured into a container, just as “Chinese cooks diced string beans a mile long / their work expanding to fill idle hours, the Pacific tides contracting / and expanding across the pretense of commerce . . .” (7). Woon’s use of ellipses and em dashes in nearly every stanza mimic these contracting and expanding motions, as oceanic currents between the U.S. and China are remembered in the bodies and lives of diasporic cooks, homeowners and misers.

“[A]mong the many rivers between us / and the many waters,” (6) the rocking is sometimes comforting, at other times disorienting. In the poem “Flight,” Woon discusses the dislocation of place: “Oak Street never had oaks: this much we knew / of the street we lived on. Aberdeen / in the encyclopedia refers you to Scotland” (10). In reference to the Satsop River, he continues: “Channel cats (catfish) either dig holes / in the muddy bottom, lodging themselves in and vacuuming / the food that drifts their way, or they / swim downstream forever” (10). The tension between embedding oneself in a place, despite a pull to return elsewhere, and floating away becomes the tidal force that ebbs and flows in this book.

In the poem “A Season in Hell,” Woon discusses the labor of working in a (probably Chinese) restaurant in San Francisco in relationship to tourism and economies of food. It opens with the following image:

‘When you come in to work each morning,

remove your bodily organs and limbs

one by one. Hang them up on the hooks

provided in the walk-in box, then put a white apron

onto your disembodied self, pick up a knife,

and go to the meat block,’ said Alex, the manager.I was also drained of blood and other vital bodily fluids. (“A Season in Hell,” 30)

Later in the poem, the gutted, ghosted and emptied speaker is at Fisherman’s Wharf, where “[t]ourists paid me to dance / on the waves; I carefully tread water and remembered to breathe” (30). Evicted, the speaker climbs down to the water beneath Golden Gate Bridge. There, “I waited until one sunny day when the water was warm and calm, / then swam all the way to Asia and got replacements for my disembodied self. / I did not forget that I was a ghost” (30). This sense of being filled up and drained, of being replaced, surprised me in this piece. I thought about the speaker being replaced when tourists pay him to dance on the waves; I thought about replacement in a line Woon writes later in another poem, “I go for egg tarts to feel Chinese” (86). The shifting and porous self of these poems butts up against the insides of their frames and containers, sometimes permeating the borders between places.

In Water Chasing Water, Woon organizes memory in terms of bodies of water. “[T]he best story is always told by a river” (17), he says, “[a]nd water, when running in one room, can be heard in the other” (21). As a connective force, tributaries and capillaries become one and the same, as water becomes blood becomes home: “[A]nd the lines on my open palms / and all the veins and arteries on my naked body / are like a road map of China” (31). Each body of water—each crush, drip and misting—remembers a town of sorts, a time of sorts, a life of sorts, that chases and slips into another. Woon writes, “if the moon and the water get together, / you can bet there will be tides. / And even a sea anemone will feel a surge of something” (39). These poems surge. He asks the reader to “take this swelling / and make it an ocean” (43).

Jai Arun Ravine,

Thank you for reviewing my book Water Chasing Water. Perhaps you are looking too intently at the text that you forget the sound and the feel of the words. I assure you that there is something beneath all those words. And there are not too many words, not for a book that took 30 years to write. You got to put yourself in your writing. Into your poetry. Otherwise you are not found anywhere.

Best wishes,

Koon Woon