Panax Ginseng is a bi-monthly column by Henry W. Leung exploring linguistic and geographic borders in Asian American literature, especially those with hybrid genres, forms, vernaculars, and visions. The column title suggests the English language’s congenital borrowings and derives from the Greek panax, meaning “all-heal,” together with the Cantonese jansam, meaning “man-root.” This perhaps troubling image of one’s roots as panacea informs the column’s readings.

*

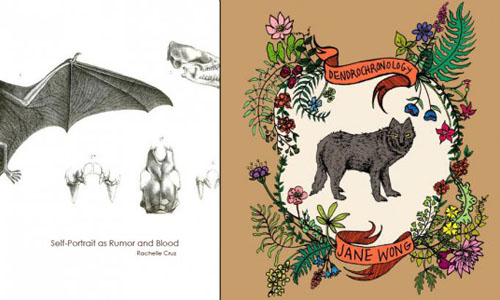

Rachelle Cruz’s Self-Portrait as Rumor and Blood and Jane Wong’s Dendrochronology

*

The cover of Rachelle Cruz’s Self-Portrait as Rumor and Blood (2012) features a skeletal exhibit of animal skulls and fangs, together with a spread-winged bat cleaved in half at the book’s spine. The back cover is a folded double of the front, which means we never see the bat’s torso or head (is it a bat at all?), only its bony limbs and the webbing between them. Jane Wong’s Dendrochronology (2011) features a floral-wreathed frame; within it, standing against a bright background suggesting a mirror or window, is a wolf turning to regard the viewer. Since these covers already work with mirror images, I’d like to hold these two chapbooks from Dancing Girl Press up to one another like mirrors, to see whether a rabbit hole might be found in the reflections’ depths. Consider the titles as well: a “self-portrait” fixes the artist’s gaze on herself, though the resulting image is of course only another depiction or illusion distorted by the medium, a rumor of sorts; and “dendrochronology” refers to those hypnotic concentric rings coded within the trunk of a tree, those layers expanding outward with time which we trace back to examine in cross sections.

In both chapbooks, the poems work within landscapes of violence and preservation. The central figure of Cruz’s Self-Portrait is the mythical Aswang of Filipino folklore, a placeholder for many ghoul/monster archetypes; here, she uses it as an object of savage exoticization, and as a mirror. These lines of verse prefigure the chapbook,

There was a girl who wanted to become an aswang

She didn’t know why aswang

While living in one country

another split her chest open

and are preceded by an epigraph from a Margaret Atwood poem:

They see their own ill will

staring them in the forehead…

Before, I was not a witch.

But now I am one.

These forcefully split identifications launch us into the chapbook. Yet, when we land on the opening poem, “Figure A,” we find it to be of formal sterility, a museum placard poem, in which a profile photograph of the Aswang is encased and described as an object for study. Throughout the book are poems in the permutative voices of the wild Aswang, as well as of those seeking to codify and domesticate it as an anthropologist or imperialist might. This diglossia speaks both to the aliveness and the deadness of a wild subject subjected by a formal language.

Wong’s Dendrochronology begins with “Cross Section,” which makes a similar play with the language of classification. She begins: “A tree felled and it was recorded as living.” The first verb here conflates the passive transitive (a tree must typically be felled by an external force) with the simple active; Wong’s tree seems not to fall, but to fell itself. Later, she writes: “When the cross section was revealed, ants / were found hiding in the scars.” This image of vitality bursting out from wounds or perceived death is prominent in the chapbook, and as we come to be guided through the examination of a tree—its diameter, height, lean direction, crown density/condition, remnant/trace, and diagnosis—we are exposed to it by a poet who finds vital wildness in the stilted observations of analysis. In “Diagnosis,” for instance, we read:

The scars of fire, flood, and lightning are mechanical, animal

The decay is severe

My arm feels abandoned

The palm of the tree is open

The open is a crater of the overgrown and after

These overlaps are marvelous in their implications. From the earlier first line, there may have been some gesture at the old koan, “If a tree falls and no one hears, does it make a sound,” but these lines mix grammatical referents so thoroughly that the animal, the human, and the dendron all share in their damages. Natural disasters are both animal and mechanical; the decay may refer to the scars, to the hosts of the scars, or to the arm, which also refers to the tree with its palm. And in the last line, again, a crater or wound opens to reveal not a cavity or absence but an overgrowth: signs of life in spaces of death.

More than personifications, these are transformations, which we also see enacted in Cruz’s poems. In Cruz’s “Cross-Examination,” the speaker is prompted several times, “State your name,” and proceeds, with a forcefulness which calls to mind Diane di Prima’s Loba, to name herself by sources of power and magic:

Immortal daughter

Pyramid of plumage.

Orange bud.

Proboscis.

Night loiterer.

Vampira.

And so on. In “Litany for Silence,” an incantatory list poem, each line ends, “I swallowed silence.” Many of those lines also include an “and” which sometimes is conjunction and other times is cause-effect: “A book of strangers and I swallowed silences. / A man pressed down and I swallowed silence.” The poem itself, of course, is a performative act of speech, a claim of ownership of a subjected past.

Dendrochronology’s second section transforms the violence of the Japanese attack and occupation in Hong Kong in 1941 into muted, natural images. For instance: “Thin rifles swing down the street. ‘Look, a parade,’ the child says, pointing.” Then, after a gap of white space: “Kimonos blossom a screaming.” In a passage describing ration lines, allocations, and stagnation, we conclude: “A cut on a finger resembles a gill,” suggesting an amphibious survival in multiple landscapes, a possibility opening out of a wound. Many of the poems in this section divert from unspeakable violence and executions, fixating instead on the painfully small, like “the ruin of tea steeping.”

The third and final section of Wong’s chapbook, set in California, seems to offer a metamorphosis which unites that unspeakable history with its “fainting / or faint, Gloss of Once, Before” preservation in the cross-section. In this section, which seems closer to the present day, we find closeness. An earlier image of “a sword held cursive to the throat” echoes and transmutes here to: “Laundry on a line curves, gives.” The ending of the book, in a cool cadence reminiscent of Gwendolyn Brooks, closes on the subjunctive, the hopeful, though it still acknowledges the past’s darkness: “We play hide, we play well. We are too good at silence. We lean against each other, mud banks. In wool blankets, we could be children. Great heaps in wolf dark.”

Self-Portrait takes us through several metamorphoses as well. The contrapuntal form of “Self-Portrait as Rumor” is arranged in two uneven columns that can be read down or across to reveal the potential beast inside the woman. It ends with the double exhortation: “keep your children in line” and “keep your children.” We see a similar gesture in another poem, “The Mother: Confession I,” in which a child is transformed through various poisons and tonics because, its mother says, “I want to keep you forever.” This perhaps vindicates the vindictive Aswang, who, we were told in “Figure A,” takes “pleasure in devouring human fetuses.” At the same time, however, in “The Anthropologist Fantasizes About the Aswang,” to “keep“ means something very different, as we go from accusation:

Monsters unfold

on my sterile table.

Thief of seed.

to vengeance: “I want to trap / her body of ruin.” And finally to domestication: “Tame her, / name her mine.”

There’s that word “ruin” again. Here, taming and naming create a productive space which invites us to consider the lines between wanting to keep, to keep from, and to keep in. The final note of the chapbook embraces the wild and vindictive for its possibilities. In the final title poem, “Self-Portrait as Blood,” the speaker invokes her blood as a genealogical but also mythic heritage, as a river (cf. Langston Hughes reclaiming tradition when he sang, “I’ve known rivers”), as a “magic of return,” and, finally, as a “wild, wild water.” Water as sustenance, but also as something in constant motion, flowing, refusing to stagnate or be penned in.

I cannot do justice to these chapbooks in such a short space. But the rabbit hole within and between them, I propose, is this: inasmuch as history is a linear narrative, it must resign itself to the straight corners of museum cards and summaries; but trees and Aswang and other wild things can tell their narratives in circles, in ripples, and in cuts which open both inward and outward, onward.

2 thoughts on “Panax Ginseng: Two From Dancing Girl Press”