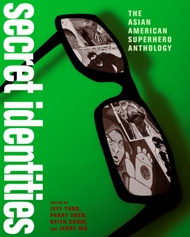

Secret Identities: The Asian American Superhero Anthology edited by Jeff Yang, Parry Shen, Keith Chow, and Jerry Ma | New Press 2009 | $21.95

Secret Identities: The Asian American Superhero Anthology edited by Jeff Yang, Parry Shen, Keith Chow, and Jerry Ma | New Press 2009 | $21.95

In September 2001, The Amazing Spider-Man published issue #477 which has been called, for its emotively blank cover, the “Black Issue.” It opens with a two-page spread of Spider-Man covering his ears in shock over the excruciating collapse of the Twin Towers. What follows is a trauma narrative as New York picks up the pieces, searches for survivors and parents and loved ones. Our pantheon of Marvel Comics gods is down at Ground Zero helping as they can, each one suddenly rendered as miniscule as the citizens: Captain America in silent grief, having seen enough world wars; Doc Doom and Magneto combining their efforts and labor without rancor; Spidey pulling his mask up halfway to drink bottled water with firefighters in the rubble.

I read a blurb once that claimed the three most recognizable characters in the world were: Hamlet, Mickey Mouse, and Superman. The effect of this Marvel shadow history of 9/11, given both the scale of the event as well as these comic book icons, is not unlike that of Ovid using Phaethon’s sun-chariot fiasco to explain desert formations, or Moses using Nimrod’s Tower of Babel to explain foreign languages. Humanity has always written itself into larger, mythical narratives in which we all cohere, in an attempt to familiarize the cosmos. The only difference is that we don’t actually believe Peter Parker and Steve Rogers exist. Yet, reading the Black Issue and getting swept up in its reverent catharsis, I do believe. For that is how literature works. That is how we construct reality in our emotional imaginations. Moreover, that is how we codify our assumptions and stereotypes—what we choose to be believable in these realities we make.

This review of Secret Identities: The Asian American Superhero Anthology is going to be a geeky review of a geeky book, so some critical bolstering may be called for. Christopher Sorrentino, writing in “The Ger Sherker” (2004), makes an explicit comparison between modern superheroes and the ancient Greek pantheon. Then he suggests its cult effect: “they [the Marvel “Silver Age” of Comics] formed the basis for a secret society equipped with its own shibboleths and cognomens for initiates to memorize and cherish.” Umberto Eco has explained at length in “The Myth of Superman” (2005) the logistics of a chronology paradox that makes the comics/myth phenomenon possible: new stories and adventures are generated about Superman (the romantic novelistic hero), who yet remains unchanged since 1938 (the untouchable myth edifice).

Of course, the cultural parallels of superheroes will make abundantly clear their relevance to a poetry blog concerned with Asian American identity and experience. Sorrentino, in the essay above, posits: “The fabulous appeal of Marvel heroes lay always in their isolation, their rejection of, and by, the worldly. And, through them, you may say, If I am alone, then I am a hero.” Further: “Out of uniform all the men may have looked as if they’d rolled off a Ken-doll assembly line [. . .] but everyone knew that they were marked by an exotic ethnicity all their own.” The X-Men are an obvious example, in recent years composed largely of teenagers secreted away in Charles Xavier’s mansion from the racism and misunderstanding/mistrust of the masses. X: for variable, for uncategorizable, for identities torn between human and mutant, between hero (model) and villain (peril), between American and Other. Now does this sound familiar?

Secret Identities collects several dozen short pieces of sequential art featuring up-and-comers from all fields—writers, illustrators, filmmakers, animators, actors—as well as industry giants like Greg Pak (Planet Hulk) and Bernard Chang (X-Men); guest appearances also include Larry Hama (Wolverine) and Greg Larocque (The Flash). The pieces range from character pinups, to complete short narrative sequences, to opening teasers of potential title works. The collection is bookended with a one-page prologue and epilogue that is a kind of call to action for the reader: someone sells a newspaper headlining “Why We Need Heroes,” someone else sings KISS’s “A World Without Heroes” and David Bowie’s “Heroes,” and a passerby witnessing a criminal getaway makes a decision to do good: he removes his glasses, looks up, and takes flight.

In short interview-like commentaries from some of the authors and editors, much insight is offered regarding the book’s mission and purpose. In the preface, Jeff Yang writes, “I think for Asian Americans, the parallels [of superhero comics] are even stronger. You’re an outsider, you don’t fit in, but then you go to school and meet other people like yourself. You discover your secret heritage—the thing inside that makes you special.” In “S.A.M. Meets Larry Hama,” we are told: “Today’s audience is very savvy. They can smell forced diversity a mile away. [to which Hama responds:] Not if you make the characters be real people despite their fantastic circumstances.” Greg Pak echoes this in “Re-Directing Comics” but replaces “real” with “compelling”:

Daredevil’s more compelling because he’s Irish Catholic. [. . .] Magneto’s more compelling because he’s a German Jewish Holocaust survivor. And the next great Asian American superhero will be more compelling because his background adds nuance and depth. Diversity enriches the entire universe in which these stories play out.

Okay, on to the stories and the superheroes. We have a few shadow histories, such as “Driving Steel” by Jeff Yang and Benton Jew in which a Chinese man called Jimson (a bastardized pronunciation of his home in Cantonese, Fo Jim Saan; his actual name “is… difficult for humans to pronounce”) uses his powers to compete against various Irish strongmen. He mentors and inspires a young child who will become American legend John Henry. In “9066” by Jonathan Tsuei and Jerry Ma, a Nisei superhero is accepted into the community and learns that it’s not the costume but the deeds that make the man; then Pearl Harbor happens and he’s thrown into an internment camp to learn anew that “it’s not what you do that matters but what you look like. I was a hero once. Now I’m just another Jap.”

We also have “The Blue Scorpion & Chung” by Gene Yang and Sonny Liew, a parody of The Green Hornet (ABC 1966-7) which for some was a milestone for bringing Bruce Lee, as Kato, to mainstream American television but which, for others, was a disgrace because he was not the superhero but the superhero’s masked chauffeur. In this parody, Chung does all the hard work and the Blue Scorpion is a drunkard who just wants the glory of the last shot. As Chung chauffeurs them away (the Blue Scorpion passed out in the passenger seat and the villain bound in the backseat), the villain asks why Chung puts up with this treatment. He answers, “The Blue Scorpion is bigger than just him, or me. The Blue Scorpion is justice. Sometimes justice requires… sacrifice.” Not the most satisfying answer, but the attempt at explaining history’s sacrifices makes this parody a significant step forward in forging a better history.

Some of the stories make full use of the superhero genre’s campiness: “The Citizen,” by Greg Pak and Bernard Chang, is a super soldier fighting for President Obama against flying Nazi gremlins. But indie sensibilities are also represented: in “You Are What You Eat” by Lynn Chen and Paul Wei, the real evil is a teenage girl’s insecurity about her weight, and the mythology is a fashion belt enchanted to “help the wearer find equilibrium between yin and yang, so that when it is removed, a healthy appetite is restored.”

Some of these stories tackle the race issue explicitly. When “The Citizen” is unfrozen after six years and meets Obama, his ignorance is used rhetorically to show how much has changed. He says, “Come on. Who sent you? [. . .] You’re black. [. . .] if you really were the President, someone would have shot you by now.” In “Just Ordinary” by Nick Huang and Alexander Shen, a comparative literature professor beats up some bad guys. In the subsequent interview, he says he’s “just a concerned citi—” and is interrupted: “—Zen Buddhist! Some kind of Kung Fu warrior monk, eh?” When he starts to say, “I teach comp—” he is interrupted again: “—uter programming! I should have known: bionic enhancements, right?”

Other stories are more subtle about the issue. In Jeff Yang’s “A Day At CostumeCo,” A.L. Baroza uses line art that crosses Disney and manga aesthetics. The cynical teenage daughter of a superpowered family is mortally ashamed of revealing her powers because, among a crowd of classic Marvel heroes, she is a sore misfit when she becomes “Pretty Super Schoolgirl Valentine,” looking not unlike Sailor Moon. “God,” she thinks, “I feel unclean.” This is presented in jest but is nevertheless part of the rhetoric of genre. It approaches the question of what is “cool,” i.e. culturally accepted, in any given mode of popular storytelling.

Aesthetic questions are especially pertinent when style—and handwriting, literally—play such a large part in this medium. Does ethnic identity have to play a role in the art at all, as when Wolverine ends up in Japan during Larry Hama’s run as writer with Marc Silvestri as artist? Regarding style, Scott Pilgrim (2010) at the front of current indie comics has imported many elements from manga page composition; I’m unaware of any controversy, but am reminded of Pound’s Cathay and his appropriation of the Chinese language not for its own sake but for American modernist poetry. Concerning mimetic style, Scott McCloud argues in his foundational Understanding Comics (1994) that the simpler a face is, the more universal its identification (think of Picasso’s grand aims at painting the universal human face by Cubifying particular ones; or think of driving directions, and whether satellite photos or drawn maps are easier to interpret). We are past the Mickey Mouse era (sidebar: Mickey = blackface?) and expect nuance of representation in people. Even Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1986; Pulitzer winner 1992), which anthropomorphized its characters, used different animals to distinguish different ethnic classes as relevant in World War II Germany. So in drawing Asian Americans, how universally Asiatic must the features be drawn? What groups are to be represented visually, and how do we accommodate complexities like mixed race? These questions become increasingly pertinent as the comic book medium, with its new highbrow name “graphic novel,” gains literary legitimacy. Especially with superheroes garnering critical and totemic respect, with graphic memoirs flooding the market, and with books like Mazzuchelli’s Asterios Polyp (2009) rippling our conceptions of form’s relationship to content. Mikhail M. Bakhtin would have been astounded to see how his principles of heteroglossia and dialogism are playing out on the new page.

But these are questions for the future. What is exciting about Secret Identities is that it represents a developing change in awareness about all the above issues. This anthology is a first and sprawling volume, and inasmuch as popular media disseminate culture, this will prove to be a major milestone in shaking up mainstream representations of Asian Americans, offering the kind of critically nuanced interaction with reality that we often seek in poetry. I eagerly await volume two and its further challenges, rewritings, and deconstructions of the “Asian American” superhero.

One thought on “Review: SECRET IDENTITIES: THE ASIAN AMERICAN SUPERHERO ANTHOLOGY”