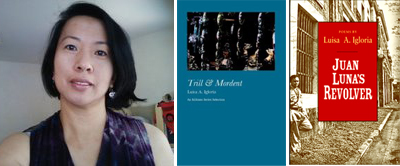

LUISA A. IGLORIA is the author of Juan Luna’s Revolver, recipient of the 2009 Ernest Sandeen Prize (University of Notre Dame, 2009 ); Trill & Mordent, recipient of the 2006 Global Filipino Award for Poetry (WordTech Editions, 2005); and 8 other books. Luisa has degrees from the University of the Philippines (B.A.), Ateneo de Manila University (M.A.), and the University of Illinois at Chicago (Ph.D.), where she was a Fulbright Fellow from 1992-1995. Other awards include Finalist in the 2009 Narrative Poetry Contest, the 2007 49th Parallel Prize from Bellingham Review, the 2007 James Hearst Poetry Prize (North American Review), the 2006 National Writers Union Poetry Prize, the 2006 Stephen Dunn Award for Poetry; and 11 Palanca Awards and the Palanca Hall of Fame Distinction in the Philippines. Originally from Baguio City, she lives in Norfolk, Virginia and is an associate professor on the faculty of Old Dominion University, where she directs the MFA Creative Writing Program. She keeps her radar tuned for cool lizard sightings. Visit her online at her web site or at her blog The Lizard Meanders.

* * *

LR: When did you first decide that you wanted to become a writer, or have you always known?

LI: I’ve always had a love for words, perhaps because my parents taught me to read early ( by age 3 ). I was also raised as an only child by parents who were twenty years apart in age (my dad was 20 years older than my mom)—perhaps this had some bearing on the way I was raised, perhaps not; in any case I remember that they took me with them a lot when they went out or to other friends’ homes to socialize, and would invariably bring a book or two for me so I could occupy myself safely in a corner and not be bored. They loved going to art events, concerts, the movies—we weren’t wealthy but my father would sometimes be able to get complimentary tickets because of work connections, and he would always be sure to include me. They took me to see a group from the Bolshoi ballet with Dame Margot Fonteyn dancing excerpts from “Swan Lake” when I was a second grader and let me stay up past bedtime to do so; but they were also just as excited by musicals like “Showboat” and in fact took me out of school early so we could watch the first run. I always knew that whatever it was I wanted to do, it would involve the work of the imagination. They’d wanted me to be a concert pianist (in fact, I’m named after a Filipina pianist popular back in their day), or a lawyer, like my father.

LR: In addition to being a poet, you’re also a teacher and a mother. Do you find that these other spheres

of identity have influenced your craft in any way? If so, how?

LI: Of course they have a bearing on what I do. For one thing, they determine the logistics of what (or how) I can do (what I need to do) in terms of time—something of premium importance to any artist. The “dreaming time” that we need, which might seem to an onlooker to be a vacant not-doing-anything, but is so essential in cultivating that inward-turning sensibility so that poems might get born. Being a teacher and being a mother and being a poet are some of the different facets of my identity; they all have something to do with each

other. But the poet side of me that must absolutely have this freedom to dream and read and make, is different from the more managerial side of me that deals with schedules. There are times in the year that I absolutely need to go away to hunker down and just be with myself and with my writing, and these are extremely important times, because they help to replenish and rejuvenate.

LR: What do you like to read? What are you reading now?

LI: It’s always a changeable, moveable feast. Just for myself (meaning, not because they’re on course reading lists for any of the classes I’m teaching this fall), I’m reading – and loving – several poetry books at the moment. Jude Nutter’s I Wish I Had a Heart Like Yours, Walt Whitman. Wonderfully realized elegies, complex in their seeing and saying. The 2009 Griffin Poetry Prize Anthology. Cecilia Woloch’s lyrical Carpathia. Amy Gerstler’s fun, risky, adorable Dearest Creature. At the moment it seems I can only manage poetry (I’ve been working on several administrative deadlines in the last two-three weeks). A week ago I bought a copy of A.S. Byatt’s latest novel, The Children’s Book, and promised myself I would start it (as a reward) only if I got done with some of these deadlines. I may get to it yet this weekend. But, I seize any opportunity to read when I get it — the other night I was waiting after class, for my daughter to get off work – she works at a bookstore, and in the hour that I waited I took Ishiguro’s new collection of stories, Nocturnes, off the shelf, and read all of the stories in it save one (the last, “Cellists” – I’ll have to go back to finish it).

LR: What artists or performers from other genres (literary or non-literary) have helped to shape your work?

LI: After Trill & Mordent (WordTech Editions, 2005) came out, I was told by a number of people who’d read it, that they found a number of references to music in the collection. I hadn’t planned on that, of course. But I realize that music has had a generous influence on my early education—I took piano lessons from the age of three, and when I was fifteen I had what folks used to call back in my home city in the Philippines, a “premiere recital,” for which I learned ten pieces (including Bach, Mozart, Chopin, Debussy, Albeniz, Bartok, one movement from Bortkiewicz’s concerto . . . ) I suppose I could have gone on to conservatory, but in college I was kidnapped by my English teachers, who sat me down for an advising session so that I became a Literature major. Visual art also finds its way into my work—many of the poems in Juan Luna’s Revolver for instance were triggered by archival material on the 1904 World’s Fair, old photographs of Filipino scholars and writers abroad in Europe in the late 1800s, and of course paintings by Juan Luna.

LR: Can you talk a little bit about process? How do you go about approaching a new piece? What inspires you or pushes you forward as you begin to write, and then shape, a new project?

LI: My process starts in that very solitary place where, like other poets (I imagine), I’m thinking and dreaming, sorting through bits of found information I’ve come across and taken down perhaps in notebooks. I don’t consciously approach writing with a set “project” or “theme” in mind. What I am most moved by about poetry through all these years, is how it works in this ineffable register—how it’s really something (in the way that we would say, isn’t that something? meaning, how amazing is it!) to note that we often don’t even know what it is that’s seized us by the hair-roots, or caught us in the gut. For me it’s a process that very much begins with intuition—in the gut, or in the heart. The “head” or thinking part of it starts to get involved as we follow the lure, whatever it was to begin with, and try to figure out what shape and structure to house it in. Sometimes a poem begins simply as image, or as sound (the sound of a line), and you begin to follow where it leads. I believe that because the poem comes from a specific sensibility (the poet’s), there is a place to come back to no matter how much change/transformation might be occurring—in the life in and surrounding the poem. Of course when one has accumulated a number of materials (drafts, poems?) one can begin to sift through them and consider what affinities are there. That’s when it becomes possible to see the shape of books emerging . . .

LR: A couple of questions about revision: From whom do you seek feedback while you’re revising? What has been the impact of community on your process?

LI: I have good friends who are great for bouncing off new poems—who will read and give their gut feedback. That’s especially important to me—that first response. Not all of these friends are necessarily writers or poets themselves, but they are all good and careful readers.

And then I appreciate being part of a community of writers in the MFA Creative Writing Program here at Old Dominion University—the camaraderie and the ability to share our lives in the context of the writing we love to do is a great experience.

LR: When (and how) do you determine that a piece is ‘finished’?

LI: I heard the poet Richard Jones once speak of this moment as hearing, internally, “an audible click” when things in the poem fall into place. That’s a pretty accurate way of summing up the experience for me. You just know that you’re done and musn’t fiddle with it any more.

LR: What writer or body of literature has had the most impact on you, and why?

LI: I’m drawn to writing/writers exploring the multilayered valences of experience and demonstrating the ability to express these nuances in language. It’s important for me that compelling works of literature are able to truthfully capture something of the sense of the utter complexity of their times—and that this sense of complexity necessarily include the view not merely from “the center” but also from the many “margins” and “fringes” where things may not necessarily be portrayed in a “mainstream” manner; where things might be more conflict-ridden, or more ambivalent, or more polyglot, or more unruly and messy . . . I think of writers like Junot Diaz, Edwidge Danticat, Salman Rushdie, and Jamaica Kincaid, for instance. But also writers like Barbara Hamby, David Kirby, Merlinda Bobis, Brian Ascalon Roley . . . my list is long and eclectic.

LR: Historical narrative is very important in Juan Luna’s Revolver. How would you characterize your personal relationship to the collective histories of the Philippines and Asian diaspora?

LI: I feel that I have been inescapably marked by these histories, even before any consciousness or awareness of them. Just having grown up in Baguio City in the northern part of the Philippines, which was designed as a hill station for the American colonial government at the turn of the last century, has made me feel in a very physical way the nexus of colonial encounters particular to the Philippine-American experience. In that the experience of diaspora has its roots in the idea of dis/location/s—I must note that I experienced multiple dislocations in language and in landscape (among other things), even before physically coming to America/leaving the physical borders of the Philippines. Someone once asked me why I continue to write about “the Philippine subject”— but I ask, how can it not inform everything I write, even if I’m (ostensibly) not writing about it?

LR: You conducted a lot of research about the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair in order to write Juan Luna. Can you talk a little bit about the process for that?

LI: As a Ph.D. student at the University of Illinois at Chicago (between 1992-1995), I had written a number of critical papers on the 1904 World’s Fair and Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri. I took voluminous notes and looked at quite a bit of research material – textual and archival (including old photographs) and there is always something particularly haunting about old photographs—the images stay with you over time. I realized I hadn’t written any poetry on the subject, but the idea to begin doing so first came to me when I was at a two week writing fellowship in St. Petersburg, Russia—I don’t know what it was: the unearthly white nights, the sense of being surrounded by buildings of historic but corroded beauty—but that’s when I first wanted to write poems about the World’s Fair. Also, I was reading some of the scholarship done by Vicente Rafael on poetry, language, and translation in the latter part of the Spanish colonial period, and I was drawn to the anecdotes of expatriate writers, intellectuals and artists—it occurred to me that the issues they faced are still the same issues that writers in the diaspora ask themselves today—or any writers and artists for that matter—what is our “subject”? Who are we talking to?

LR: Juan Luna is, in many ways, a distinctly political project. To what extent do you think an artist has a responsibility to directly engage with political dialogue in his or her work? In what space or context do the roles of artist and the activist begin to intersect?

LI: The question about the intersection of art and activism (or “politics”) is always an interesting one. Without belaboring it too much, I believe that art does not arise out of a void, and that it is effective when it makes heartfelt human connections, and even more so when it enables a sense of agency (the belief that there is something we can do in the world so that change might be effected). There is power in its ability to engage memory and intellect, compress and distill emotion, idea, and experience—and it is this power which poets and writers seek to harness when speaking to others through their art. Why does one have to sing, when there is suffering? Why is beauty necessary, when there is so much poverty or violence or depravity in the world?

LR: What are you working on now?

LI: I have a new manuscript tentatively titled Flesh Lyric, Rebel Lyric, which I’m sending around to various places either in whole or via individual poems.

LR: Do you have any advice for young poets just out of, or in the midst of, writing programs?

LI: Don’t lose whatever fuels your passion for life and for language. Don’t lose the fire in your gut.

Thank you LR for this thoughtful conversation with a truly great poet! I’m glad to get some insights from the source!

Thanks for stopping by to peruse, Tom! We’re glad you enjoyed it!

So many wonderful and wise insights–great interview!

Yes; we were thrilled to hear what she had to say!

Thanks for stopping by!

I especially love this:

“I believe that art does not arise out of a void, and that it is effective when it makes heartfelt human connections, and even more so when it enables a sense of agency (the belief that there is something we can do in the world so that change might be effected). There is power in its ability to engage memory and intellect, compress and distill emotion, idea, and experience—and it is this power which poets and writers seek to harness when speaking to others through their art. Why does one have to sing, when there is suffering? Why is beauty necessary, when there is so much poverty or violence or depravity in the world?”

It’s just what I needed to hear while I am in the middle of a writing project. Thank you for inspiring me, Luisa. And congratulations Lantern Review–I look forward to more.

Dear Iris: I love this interview with Luisa Igloria, and how she says she’s “drawn to writing/writers exploring the multilayered valences of experience and demonstrating the ability to express these nuances in language”. It made me think of Trevor Joyce’s poem, “Construction”, which I just re-encountered, altogether loving his closing section: “My brain had built / A scheme of echoes, / Of ancient meanings held / In rock, in sunlight on ice, / In the low beginnings of thunder // But this wall needed no exterior / Aid for its stability, / No echo in its circumstance.” Also loved the mention of Junot Diaz, whose book, Drown, I’m just getting neck-deep in. Lantern Review is looking really great, dear. Thanks for creating this literary space.

Desmond: Thanks so much for stopping by. So glad you’re enjoying our content! Junot Diaz’s work is indeed wonderful. I had the chance to hear him read at UND last semester, and his delivery was fantastic.