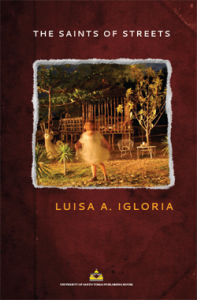

The Saints of Streets by Luisa A. Igloria | University of Santo Tomas 2013 | $17

“Hokusai believed in the slow / perfectibility of forms” (3), begins Luisa A. Igloria’s newest book of poems, The Saints of Streets. She has been writing a poem a day since 2010, a project archived online and from which this collection was born. Given how prolific she is, I could not help but find in these opening lines a reassurance that the poems collected here are not merely practice but are a practice. For perfectibility, the poem goes on to say, is “the way, // after seventy-five years or more, the eye / might finally begin to understand / the quality of a singular filament—” Indeed, this is a book of single filaments, and in these poems are so much delight and wisdom, often beginning in the mundane but nearly always spiraling inward to the sacred.

We see this spiraling quality first of all in the poems about place, which is one of what I’ll call three clotheslines bending with this collection’s poems: clotheslines, I say, because of the quality the poet gives to everyday activity, weighted with meditations even as it flutters in the wind. The place poems nod most pronouncedly to the collection’s title. In “Repair,” for instance, we begin in the present moment: “Almost at the alley’s elbow, I know the gate . . .” (9). Shortly after that, we move to the wistful past tense, each sentence beginning “There used to be” as a litany. Just as we first graze the alley as a kind of body, so does the speaker name the ghosts of objects as though in mortal lament, counting down structural losses, strippings, and repairs along with the absences of people. But the magic of this poem is in its concluding grammatical shift. See how, in the last three lines, the past tense makes way for something closer to the timeless:

across the south wall, even on the night the child

ran out the side door with bare feet, crying after the figure

disappearing halfway up the rise, beyond the street.

Line by line we move from a definite point in time (“on the night”), to an ongoing and simultaneous action (“ran out . . . crying”), and finally to an image marked by its remove from the rest of the action (“disappearing . . . beyond”). The medial caesura of each line helps us rhythmically, step by step, as do the definite articles. The final “disappearing” is a present participle, non-finite: not quite past and not quite present. And that last image of what is “beyond the street,” in its ghostly way, takes us through the longing into something even greater than the object of the longing, greater than the body of the street.

Continue reading “Review: Luisa A. Igloria’s THE SAINTS OF STREETS”