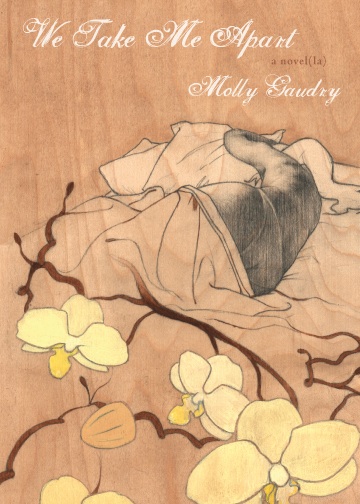

Molly Gaudry is the author of the verse novel We Take Me Apart (Mud Luscious Press, 2010), which was named 2nd finalist for the 2011 Asian American Literary Award for Poetry and shortlisted for the 2011 PEN/Joyce Osterweil. She is the creative director at the Lit Pub.

* * *

LR: When did you start writing and how did you become a professional writer?

MG: I declared creative writing my major in high school—at the School for Creative and Performing Arts in Cincinnati, Ohio—and graduated with a vocational degree. But I was always writing before that, making up little stories either in my head or putting them on paper. As for becoming a professional, I don’t know: does that come with your first publication (in my case, “The Bees,” in the now-defunct magical realism magazine Serendipity), or with your first book (We Take Me Apart, Mud Luscious Press), or does it start inside of you (I am a writer, I commit myself to this fully, I won’t quit until I have made it so)?

LR: We Take Me Apart stands at the intersection of poetry and prose, defying the conventions of either genre. Can you talk about the inception of the book and how you found its unique structure?

MG: It’s called a “novel(la)” on the cover, but that’s because it was the first of Mud Luscious’s “novel(la)” series. I’ve always called it a “verse novel” or a “novel in verse,” when explaining it to others: “It’s long like a novel, but each chapter looks like a poem.” I can’t say I was actively aware of subversion while I was writing it. I look at it now, after studying poetry for three years in the MFA program at George Mason University, and I can see how my line endings are somewhat subversive to more poetic line ending conventions, and I can see how having lines at all is subversive to prose conventions. But I wrote that book before the MFA, before any real poetry awareness. So really it was a fiction experiment. For me, a new way to tell a story, a different way to write a novel.

I realize something else now, too: I think that the form provided me with breathing room during a very claustrophobic time of my life. I had just left Cincinnati after graduating with an MA in fiction, and I was living in a room-for-rent in South Philly and teaching Pre-GED and GED courses in a halfway house for post-incarcerated men and women a few nights a week. It was depressing as hell. I felt confined to my room, and I felt confined in that jail, and I felt confined by my life. I didn’t know what next, where next, when next. The book’s form evolved throughout the drafting and editing stages, but in the end all that white space on every page probably gave me some peace, a place to breathe, to sigh.

LR: Although it had an indie publisher, We Take Me Apart received good deal of mainstream critical attention. What do you think this might say about the changing landscape of publishing?

MG: I’m going to cheat on this one and share a Q&A from an interview with Nicelle Davis at [PANK]. Nicelle asked: “How do you think the writing traditions of the past are manifesting themselves in the literary world today?” And my answer was (and still is): “When I see the phrase ‘writing traditions of the past,’ I think not of great literary movements but great literary partnerships (between writer, who dared, and publisher, who believed in that daring). This is the only tradition that matters. It is the one—not manifesting, but—being kept alive today, on an awesome and inspiring scale. And it is exciting.”

LR: What did you learn from the experience of publishing We Take Me Apart as far as the business end of producing a book? If you could travel back in time knowing what you know now, what advice would you give yourself before you first published?

MG: I think what I learned is how valuable it is to love your publisher, to trust in him (or her) wholeheartedly. This relationship is like a marriage—you are bare and vulnerable, utterly exposed. So do not enter into it lightly.

I was so lucky to have found J. A. Tyler. He championed the work from the start and signed on to publish it before ever seeing the first full draft. He believed in the promise of those early pages. He encouraged my creative process (even if it was maddening) and he actively and attentively read new pages every step of the way throughout the early and later drafts. He copy edited ruthlessly, lovingly, and midwifed the book into the world.

Love your publisher. Expect your publisher to love your work. Do not settle for anything less.

LR: In addition to poetry, you have also written a short fiction collection, Lost July, published in the 3-author volume Frequencies (YesYes Books). How does your process for writing fiction differ from your process for writing poetry?

MG: So in both cases (and actually in most cases for me), I write from word lists. We Take Me Apart began with jumbled words from Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons. I pulled a word and wrote a line. The stories in Lost July began with a phrase-per-page from various zines—The Las Vegas Weekly, Washington City Paper, The Boston Phoenix, LA Weekly, etc.—and all of the zines were sent to me by friends from around the country. Although only eleven stories made it into the final manuscript, the project began as an idea to write thirty stories inspired by thirty city zines from the week of my thirtieth birthday.

LR: When you sit down to write, how does a poem come to you? What are you most aware of: story, image, or sound? How would you describe your writing style and what does it allow you to accomplish with your poems that other styles might not?

MG: I don’t like the blank page and actively avoid it. Word lists are a necessity. There may be other constraints I might like to try out in the future, but for now I love the intimacy of working with other writers’ words, reshaping them, reviving them into new forms. So, after the words themselves, which I choose quite selectively from selectively chosen books by selectively chosen authors, I’m probably most interested in finding the narrator’s voice—and quickly. If the words don’t get me to a voice I can love within the first 10 pages or so, the project usually stalls out and lands in my abandoned manuscripts pile. I don’t mind this, abandoning projects. It’s the voice that matters, that carries readers through a book. And maybe this is why I love the verse novel form—the narrator has an entire book length to live her life and tell her story, but she can do it any damn well way she pleases from page to page.

LR: Tell us a bit about the Lit Pub. What gave you the idea to start it and how does it work?

MG: Oh boy. Lit Pub started as something else entirely. That idea just wasn’t sustainable. Today, Lit Pub is a tiny little publishing company (we’ve published established authors like Aimee Bender and Miles Harvey, and we’re committed to publishing first books by emerging authors like Liz Scheid and Andrea Kneeland). We have a fancy website and we use it to recommend books you may or may not have already heard of.

LR: Having worked in both print and digital media, what are your thoughts on print versus online publishing? How do they differ? What are the pros and cons of each?

MG: It’s great to have a book in print. But just let everything else go free into the world, however or wherever it is released. There is no room in this business for elitism or snobbery. (This is my favorite thing to say, and I say it a lot: If the Buttcrack Review asked me for a poem, I’d send them three.) Release your writing into the world and let anyone who wants it (loves it) have it. Make sure you respect their work, their journal, the writers they’ve published (remember, it’s always a serious relationship), but just free yourself from the work and let it go home (to any home where it’s welcomed with open arms). Publications are cumulative. One leads to another and another and the next. I don’t like to think of print or online as majorly different things. It’s all just an editor on the other side, a publisher on the other side, and if you respect and admire them, and if they respect and admire you, what else matters?

LR: To what extent do you use social media professionally? Do you think it’s necessary for a poet’s success that they be active online?

MG: I used to be a lot more active on Facebook. Now I mostly just post pictures from my phone. But I like to check in every so often and see what others are up to, and I like to have it so I can find people and so people can find me and so we can keep some sort of connection alive.

I’m on Twitter, and although it’s more public than Facebook (because anyone can see it), I feel a lot more anonymous blurting things out into the Intersphere.

But these things come naturally to me. I like Facebook, and I like Twitter. I like connecting with people—commenting on their posts, sharing their good news, retweeting or replying to their funnyisms.

My advice is this: if you are a writer and you don’t like these things, don’t for the love of God try to fake it. You’ll hate it, it’ll take time away from your writing, and people will see right through your awkward, painful attempts. But if you are a great reader, be proactive and book yourself a tour! If you are a great organizer, plan an event! Whatever you like, find a way to make it work for you.

And most importantly: promote others. Share, comment on, retweet, plan an event for, write fan mail to, write a book review (or poem review or story review) for OTHER WRITERS! It’s not about you, it’s about the literary community and how to help it thrive. By celebrating others, you nurture the community that will in turn celebrate and nurture you.

LR: Can you tell us what you’re working on now?

MG: In the spring, I began Ogie: A Ghost Story (the sequel to We Take Me Apart), and I finished the first draft at the end of July. I let it rest all of August. But now, with the new fall season upon us, I’m getting ready to go back into it and begin revising. Here’s a teaser:

she has gone so long without water her mouth skin is cracking

it has been too lonely for her in this house

I ask how she feels today and she says BELOW THE WEATHER and that she is IN NEED OF MEAT AND SEX

she tells me she had fourteen children

her husband and their seven sons and depending on if the last girl lived or died their six or seven daughters survived her in a city far away

she wonders if they thought of her often and admits that anymore she does not think of them that often

even her great-grandchildren have grown old and died

if I could I would find them and ask them here and hold them for her

because I am sinew and she is ancient as trees