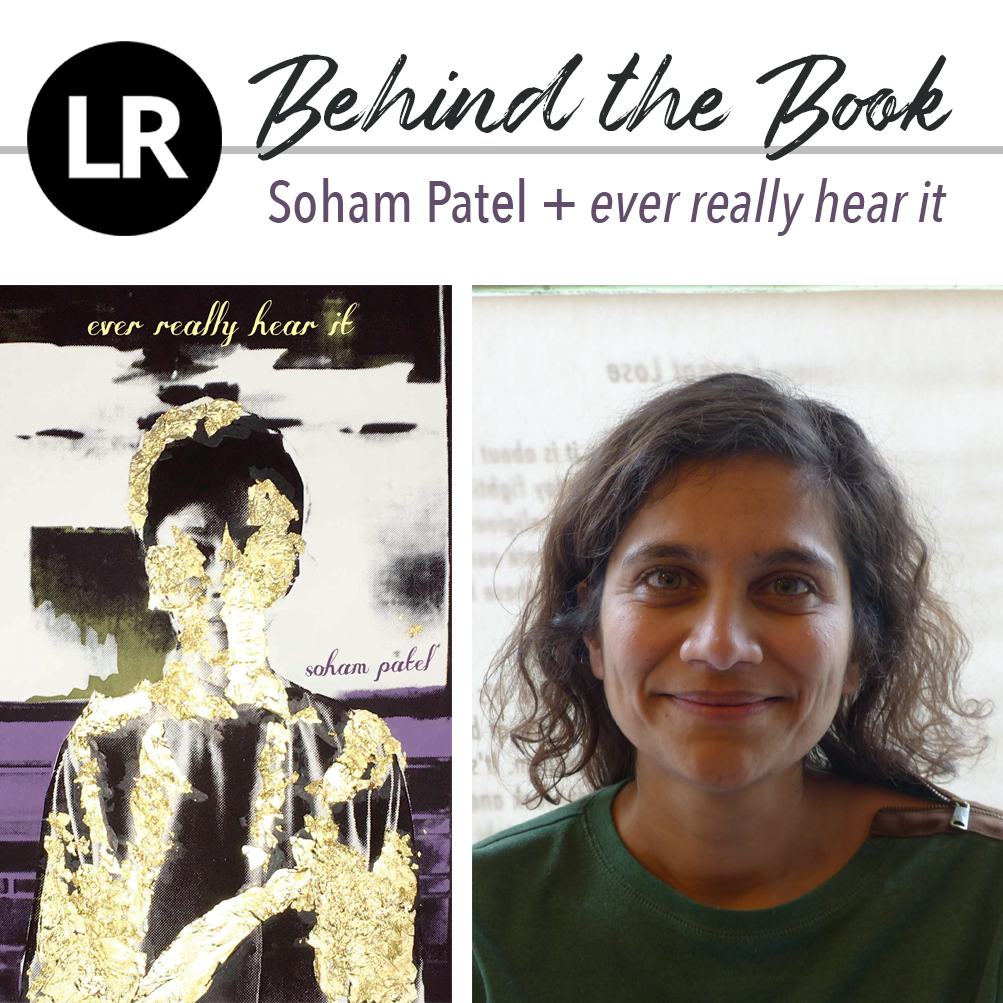

In “Behind the Book,” we chat with authors of new or recent collections about craft, process, and the stories behind how their books came into being. For this installment, we spoke with poet Soham Patel about punctuation, music, the rituals of preparation that surround her writing practice, and the James Baldwin story that inspired her gorgeous second collection, ever really hear it (Subito, 2018).

* * *

LANTERN REVIEW: Where and how do you like to work when you write? What rituals help you to persist when you come to the page?

SOHAM PATEL: In my writing practice, I attempt to balance a fair amount of discipline and play. I like to write poetry in my home. My poetics believes that we embody language when we come to the page, so in terms of rituals I have several that persist: like these days, it’s making sure I do, even for just a few minutes, some kind of meditative exercise—like walk the dog or some yoga, even if it is just one concentrating breath to declutter my mind and detox my body. I also like to tidy up my home and then read as a way of honoring the work that’s been done before mine and has brought me to this privilege of being able to write. So today, for example, I skimmed these interview questions, folded some laundry and swept the floor, then reread James Baldwin’s short story “Sonny’s Blues” before sitting down to write this.

LR: ever really hear it takes its title from a James Baldwin quote: “All I know about music is that not many people ever really hear it.” And, in fact, music, sonics, and performance are a central motif of the book. Why music? Can you tell us a bit about how you came to choose music as a connecting thread?

SP: The protagonist in “Sonny’s Blues” utters this sentence in the final scene while he’s watching Sonny play jazz music onstage at a nightclub in Harlem. Baldwin writes so beautifully about music’s power, its ability to be both a cure and a force that could break you into a bunch of pieces. Sometimes we burst into song like we burst into tears or laughter. When I was growing up, music was ever present because my family spent a lot of time in cars, where my parents would play their tapes from India between songs my sister and I asked to listen to on the local radio stations. Music is a mystery to me in terms of just how its power works—to change a mood, for example, and how it works on a disciplinary level because I don’t know how to read it. ever really hear it was born from my thesis at the University of Pittsburgh MFA, where I was using my time to explore these questions I had about music through poetry. Ben Lerner taught us about how Jack Spicer believed the poet was transmitting messages from radio static. Poetry was a chance to interrogate lyric’s limits and the possibilities of the speaker in many contexts.

LR: Many of the poems in the book are headed by a series of four colons in lieu of titles. And, in fact, the colon becomes much more than a punctuation mark throughout the book—it’s a linkage for analogous terms, a break, a permeable membrane, a connecting track, a beat or rest in the line of the lyric, a musical notation in and of itself. Can you tell us more about the thought that went into this choice? Why the colon, and how did you settle upon the internal grammar of its usage throughout the book as you were putting the project together?

SP: The project—as a book—for me is, most importantly, a made thing. Most of the poems are meant to sit on one page so that the physical act of the turning of the page becomes a part of the pause that occurs while moving through the book. There are five poems towards the beginning of the opening section that perform as a sequence across more than one page and are connected by the “::::” colons. In early compositions I repeatedly listened to the Yeah Yeah Yeahs song “Gold Lion” four times and wrote while trying to focus my listening to just the drums, then again for each guitar, then just focusing on Karen O’s words and vocables. At MFA school, Dawn Lundy Martin had us study Myung Mi Kim’s Dura, and that’s where I first saw the “:” on the page, hanging out at the top where a title should be, in a place where a colon traditionally would not be found. The subversion was so vanguard to me, and I began to think about how breaking punctuation rules might be necessary when building a poem’s structure in order to keep the language of it live. I am drawn to the stacked order and open space the colon holds, the way it is a parallel, mirrorlike. Four in a row is like a stutter to me and also an ellipsis turned to a stop. I wanted the colon to do all the things you list—and pay homage to Dura’s sequences.

LR: The work, as assembled, feels so beautifully seamless—like a continuous whole rather than a group of poems collected together. How did you go about approaching the shape of the project as you were composing?

SP: Thank you. In a manuscript workshop at MFA school, Lynn Emanuel suggested we make sure the last line of one page carried on somehow to the first words on the next page. After about four years of drafting the poems, the titles felt like a distraction, so I removed most of them, then titled each page “song:”—but that approach felt incorrect (like a placeholder), too, so I then removed titles and spent a couple more years moving each page into different movements. While I was doing this, I was also assembling the poems for my first book, to afar from afar, which was initially arranged based on the three Ayurvedic body constitutions, and so I decided to also try this structure out with ever really hear it. In the end I flipped the order and put the last movement first.

LR: A personal craft question for you: What are the road signs, the internal notes that tell you you’ve arrived, when you’re writing—whether you’re working on an individual poem or a larger project? How do you know when a poem is finished? How did you know when this manuscript was ready to go out into the world?

SP: In practical terms, I needed to send the manuscript into the world in hopes that it would get picked up so I could be considered for the kind of employment I was seeking after I earned my PhD. Otherwise, I practice poetry through large projects that require intense study, durational scope, and can take on various forms. I revise obsessively—and slowly. For this book, I approached the poem as I would a song. I used to play the guitar and sing, so memorizing lyrics and chord progressions has been embedded into me. A poem on a page is finished when I have it memorized—not always by heart but sometimes by sight or by ear; I can encounter the first line and anticipate what’s coming next, where and why the next en- or em-dash appears, and even where there’s space for spontaneity when performed. A good road sign for me is that when I can fully embody the poem (or it me), I have no doubts about each part of it and can account for every strategy made in building a thing that is solid but still porous.

* * *

Soham Patel is the author of the poetry collections to afar from afar (The Accomplices, 2018) and ever really hear it (Subito Press, 2018). A Kundiman fellow, Soham is also an assistant editor at Fence and The Georgia Review.