Panax Ginseng is a monthly column by Henry W. Leung exploring the transgressions of linguistic and geographic borders in Asian American literature, especially those which result in hybrid genres, forms, vernaculars, and visions. The column title suggests the congenital borrowings of the English language, deriving from the Greek panax, meaning “all-heal,” and the Cantonese jansam, meaning “man-root.” The troubling image of one’s roots as a panacea will inform the column’s readings of new texts.

*

*

First, let’s give pause to these lines from Richard Hamasaki’s “Guerrilla Writers,” from which I take the title of this post:

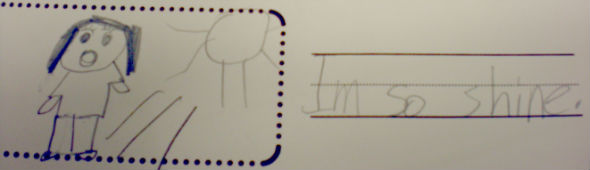

golden rules of english?

conspiracies of languages?memories unwanted

works are left unknownif what’s to be spoken

needs to be writtensabotage the language

ignore the golden rulesguerrilla writer

barbarize the rules

Keep in mind that the capitalization of lines and proper nouns is endemic to the English language’s hierarchical structure, and keep in mind Hamasaki’s argument as I discuss the politics, the rhetoric, and the aesthetic of Hawaiian Pidgin as a metonym for “Asian American” literature and letters.

Here’s a passage from the New Testament, translated in 2000 by Wycliffe Bible Translators. This translation is from Da Jesus Book and the passage is from Matthew Tell Bout Jesus 14:29-31:

Peter climb outa da boat, an walk on top da water fo go by Jesus. But when he see how da wind was, he come scared, an start fo go down inside da water. Den he yell, “Eh, Boss! Get me outa dis!”

Right den an dea Jesus put out his hand an grab him, an say, “How come you trus me ony litto bit? How come you tink you no can do um?”

That’s a heavily accented Hawaiian Pidgin, or Hawaiian Creole English (HCE). New translations or modernizations of the Christian Bible are not infrequent, but there is something unsettling about having the cultural disguise of language so blatantly unveiled. We are not used to so vernacular a Jesus Christ. Amazon.com reviews of this translation are adamant in their reassurance that this use of Pidgin is not a joke or mockery. The University of Hawai’i’s production of Shakespeare’s Twelf’ Night o’ Whateva some years ago comes to mind: I wondered then about the politics of responses to such a performance: were there worries of Pidgin being used as kitsch or as a dumbing-down? Is “translation” inherently an imperial process, the imposition of one culture’s narratives upon the linguistic framework of another? It can sound like the dramatic donning of a persona. The Wycliffe translators seem at least to recognize Hawaiian Pidgin as a language system on a level with Standard English: in their introduction, they note that their translation works from the Greek (though whether Masoretic or Septuagint they don’t say) rather than from other derivative English translations. Continue reading “Panax Ginseng: Barbarize the Rules (pt. 1 of 2)”